다 함께 거꾸로 움직여 봅시다: 리듬과 안무된 걷기의 정치

“다 함께 거꾸로 움직여 봅시다”1

리처드 롱은 윌트셔(Wiltshire)의 한 들판에서 가상의 직선 하나를 따라 걸어갔다 돌아오길 반복했다. 걸음이 닿았던 곳의 풀은 꺾이고 짓이겨져 그렇지 않은 곳과 음영의 차이를 만들었고, 걷기로 만들어진 선(1967)은 그렇게 걸음으로 인해 남은 선명한 선을 풍경의 가운데 두고 찍은 사진 작업이다. 하지만 이런 배경 이야기를 모르더라도, 사진은 ‘지금 여기’에는 없으나 ‘그때 거기’에는 있었던 어떤 움직임을 말하고 있음을 우리는 쉽게 알아챌 수 있다. 곧게 뻗은 하나의 선은 풍경 속에서 다른 요소와 구분되는 무척 인위적인 흔적이기 때문이다. 걸음은 흔적을 남긴다. 팀 잉골드는 인간의 문화적 행위인 걷기, 짜기, 엮기, 이야기하기, 노래하기, 그리기, 글쓰기 등은 모두 선(lines)을 따른다는 공통점이 있다고 말한다. 그리고 그는 선을 크게 두 가지로 분류하는데, 하나가 실(thread)이고 다른 하나가 바로 흔적(trace)이다. 흔적은 “지속적인 움직임에 의해 단단한 표면에 남은 표시”로, 그것은 대개 가산적(additive)이거나 감산적(reductive)2이다. 연필을 종이에 대고 그었을 때 흑연이 레이어로 더해지며 선이 생기는 것이 가산적인 것의 예라면, 날카로운 도구로 돌에 생채기를 내는 것은 감산적인 것의 예이다. 여기서 잉골드는 걷기로 만들어진 선이 가산적이지도 감산적이지도 않다고 말하는데, 왜냐하면 리처드 롱의 걸음은 무언가를 더하거나 뺌으로써가 아니라 풀을 밟았을 뿐이고 그 자리에 비친 빛으로 인해 일시적인 선이 드러났다는 것이다. 잉골드의 서술에 분류에 대한 고집스런 면이 있는 것은 사실이지면, 이를 분류의 규범으로만 국한해 이해할 필요는 없을 것이다. 그보다 중요해 보이는 것은 가산적이거나 감산적인 것 사이에 놓인 흔적의 다양성, 바꾸어 말하면 힘의 작용과 그에 따른 변형의 무한한 양태를 추측할 수 있는 상상력이다. 안무된 걷기의 정치를 말하기 위해서는 바로 이 상상력과 관련하는 인식론이 필요하다. 안무된 걷기는 리듬을 변형하고, 그것은 대개 가시적인 표시로 남지는 않기 때문이다. 반복해서 말해보자면, 걸음은 흔적을 남긴다.

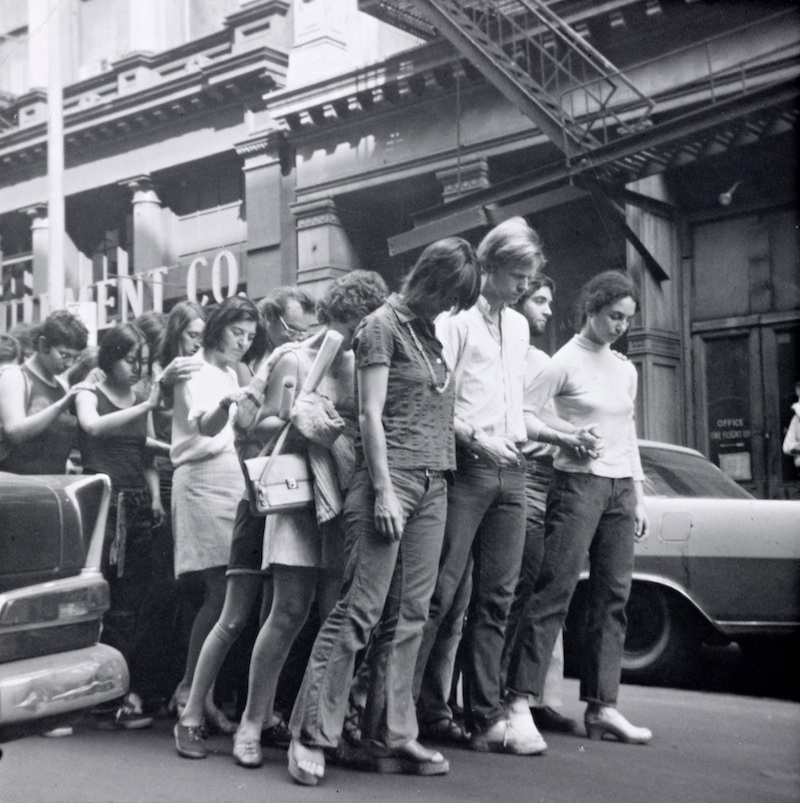

하지만 걸음은 이미 흔적이기도 하다. 걷기는 ‘원래 그러한 것’이기에, 혹은 너무 사소한 사건이어서 의문이나 질문의 대상이 될 수 없는 것처럼 보이지만, 지나치게 자연스러운 이 행위조차도 사회적이고 문화적인 힘과 개인 사이의 역학의 산물이다. 마르셀 모스는 이를 “사회마다 사람들이 전통적으로 자기 몸을 사용하는 방법”으로서 몸 테크닉(Les techniques du corps)이라고 개념화한다. 모스는 다양한 문화의 몸의 사용을 관찰함으로써 한 사회나 문화 안에서는 자연스럽다고 여겨지는 몸짓이 어떻게 인위적으로 구성된 것인지를 밝힌다. 모스는 오니오이(onioi)라고 부르는, 마오리족 여성들 사이에서 전승되는 엉덩이를 이리저리 흔들며 걷는 걸음에 대한 엘스던 베스트의 서술을 소개하는데, 베스트의 표현에 따르면 이 걸음은 ‘훈련된(drilled)’ 것이다. 몸 테크닉은 한 시대에 양성된 ‘체조술’이다. 모스는 몸을 사용하는 기술에는 교육과 모방이 핵심적임이라고 주장하며 다음과 같이 말한다. “비록 자신의 신체와 관련된 단지 생물학적인 행위일지라도, 외부에서 그리고 위로부터 강제됩니다. 개인은 다른 사람들이 자기 눈앞에서 혹은 자신과 함께 수행한 행위로부터 구성되는 일련의 동작을 차용합니다. 모방하는 자에 대해 질서정연하고 권위 있고 검증된 행위를 하는 자의 위엄, 바로 이 개념 안에 모든 사회적 요소가 존재합니다. 또한 그로부터 일어나는 모방행위 안에 모든 심리학적 요소와 생물학적 요소가 존재하지요”3 몸 테크닉은 “효과적인 전통적 행위”로서 몸들을 건너며 전승되는 것이다. 물론 전승이라는 것이 대체로 그러하듯 그것은 여러 이유에서 변형된다. 예컨대 터치스크린 장치의 탄생과 함께 성장한 세대는 전화를 걸기 위해 번호를 누를 때 엄지를 사용하지만, 아날로그 전화기를 사용하던 세대는 터치스크린 스마트폰을 사용할 때에도 여전히 검지를 이용해 버튼을 누르듯 스크린을 터치하는 모습을 종종 볼 수 있는 것처럼 말이다. 대부분의 몸 테크닉이 생겨나고 사라지고 변형되기를 멈추지 않지만, 그것이 어떠한 이유에서건 구성되고 형성된 것이란 사실에는 변함없다.

몸 테크닉의 전승과 변형에 대한 모스의 생각을 우리는 리듬에 관한 문제로 바꾸어 생각해볼 수 있다. 리듬은 질서의 발명과 관련한다. 우리는 보통 어떤 흐름 속에서 규칙적으로 반복되는 패턴을 알아챘을 때 리듬을 인식한다. 한편으로는 규칙적으로 반복되는 패턴으로 리듬이라는 흐름을 생산한다. 리듬은 세계에 질서를 부여하고 또 질서를 재생산하는 일이며, 반복은 몸 테크닉의 전승과 변형에 있어서 필수적인 조건이다. 반복되지 않는 것은 사라진다. 혹은, 반복되는 것을 체화함으로써 몸은 어떤 리듬을 기억한다. 리듬 분석의 아버지인 앙리 르페브르는 우리의 몸과 리듬의 관계에 대해 다음과 같이 말하며 끊임없이 몸의 중요성을 강조했다. “몸은 서로 다르지만 조화를 이루는 리듬들의 꾸러미(paquet)로 이루어진다… 몸은 리듬들의 다발(gerbe), 다른 말로 리듬들의 묶음(bouquet)을 만들어 낸다.”4 르페브르에 따르면 몸은 무수히 많은 리듬의 묶음이고, 다양한 리듬과 관계를 맺는다. 그는 이 관계의 양태를 동일리듬성, 다리듬성, 조화리듬성, 부정리듬성으로 구분하는데, 이는 다분히 정치적인 감각을 환기시킨다. 동일리듬성은 지휘자가 주도하는 하나의 리듬이 연주자들에게 확장되는 것을 예시로 들 수 있으며, 다리듬성은 “다양한 리듬의 구성”을, 조화리듬성은 “다른 리듬들의 결합을 전제”한다. 부정리듬성은 리듬들의 ‘탈동기화’이다. 르페브르는 이 리듬의 역학을 사회적 관계 모델로까지 확장하는데, 동맹을 일종의 조화리듬성으로, 분쟁을 부정리듬성으로 표현하는 것이다.5

안무된 걷기와 관련하여 여기서 보다 의미심장하게 주목되는 것이 바로 부정리듬성이다. 규범화된 일상성 속에서 조화롭게 결합된 리듬이 깨지면 “고통이 찾아오며 병적인 상태에 진입하게 된다… 리듬의 불일치는 기존에는 조화리듬적이던 조직에 치명적인 무질서를 초래한다.”6 조화가 깨지며 병리적인 것이 발현되기 시작하는 부정리듬성은 언뜻 우리의 관습적 윤리 안에서 부정적인 것으로 느껴진다. 하지만 여기서 우리의 일상을 지배하는 자본주의의 리듬에 비판적인 입장을 내세운다면, 오히려 자본주의라는 허구가 생산하는 리듬과 결합되고 조화되는 안정성은 벗어나야 할 무언가가 되며, 그것을 어긋내는 부정리듬은 새로운 시공간을 창출하고 새로운 주체성을 형성하게 해 줄 가능성의 운동성이 될 수 있다. 리듬을 하나의 존재론이자 인식론으로 삼는 일은 외부의 리듬에 관하여 ‘나’가 보다 주체적으로 그 리듬과의 관계를 설정해 나가기 위한 단초다. 내게 자연스럽게 주어진 것을 자연스럽게 여기지 않는 일, 병리적인 것을 품어내는 일, 그리고 다르게 걷는 일. 이는 미셸 드 세르토가 ‘일상적 실천’을 탐구하는 프로젝트를 밀고 나간 문제의식과 적확히 공명한다. 세르토가 탐구하는 일상적 실천이란 지배적 경제 질서가 강요하는 바대로가 아닌 다른 방식으로 생산물을 사용하는 것, 즉 리듬을 어긋내는 소비자의 능동적 재생산 행위를 살펴보는 것이다. 그것은 수용과 저항의 양극단 사이에 놓인 무수히 다양한 진동의 양태라고도 할 수 있다. 세르토는 이러한 재전유의 전술이 새로운 공간을 창출한다고 보는데, “소비자들은 기술관료적으로 건축되고 표현되고 기능적으로 만들어진 공간 속을 오간다. 그런데 이 공간 속에서 소비자들의 경로는 예측 불가능한 문장들, 부분적으로 판독 불가능한 ‘지름길’을 만들어낸다. 관용적 어휘들로 구성되어 있다고 해도, 또 규정된 통사론을 따르고 있다고 해도, 소비자들의 경로는 다른 이해관계와 욕망의 책략을 그린다. 이 책략은, 경로가 펼쳐지는 시스템에 의해 결정되지도 포착되지도 않는다.”7

그리고 걷기는 세르토가 중요하게 다루는 ‘일상적 실천’중 하나다. 아니, 걷는 사람들은 도시의 일상적 실천가들이다. 흥미로운 것은 그가 걷기를 언어 행위와 등가적으로 살핀다는 것이다. 세르토에게 있어 걷기는 일종의 ‘발화’ 행위인데, 그것은 보행자로 인해 공간의 질서가 실체화되기 때문이다. 여기서 보행자는 기존 질서를 따를 수도, 그것을 변형시킬 수도 있다. 진입 금지 표시가 된 길을 걷지 않는다면 그것은 진입이 금지된 길이 되는 것이고, 그럼에도 그 길을 걷는다면 그것은 결국 다른 길이 된다. 보행의 수행성(performativity)이다. 세르토는 또한 걷기를 일종의 수사학으로 여기며 몸짓을 ‘문채’에 비유한다. 보행자가 ‘어떻게’ 걷는가는 도시를 “뒤틀고 파편화 하며, 도시의 부동의 질서에서 벗어나게 만든다.”8 여기서 우리는 이본 라이너의 시와 안무의 관계를 두고 이러한 실천의 예시로 말할 수 있다. 그의 시 도시에서 걷기를 보자.

도시에서 걷기

이본 라이너

난 여전히 하루 중의 이 시간을 사랑해

첼시에서부터 동쪽으로

남쯕으로 세인트 마크까지

이 빠진 달

가을의 탑을 청소하기

태양의 빛 속에서 각각은 빛난다

가능한 오랫동안 문신 시술소를 지나쳐

손금 읽는 사람들, 작은 그리스 음식점, 잡화점을 지나쳐

아직 숨 쉴 공간이 남아 있다

이 게걸스런 마을에서

계속 움직여라9

이 시에서 이본 라이너는 도시 안에서 걷는 주체의 행위를 안무화 한다. 대단히 특별한 몸짓을 고안하는 것이 아니다. 시적 화자는 도시의 “숨 쉴 공간”을 찾아 자신의 걸음 속도를 조절하며 도시의 가로세로를 가로질러 두리번거린다. 그리고 무엇보다 중요한 것은 “계속 움직여라”라는 마지막 주문이다. (비트겐슈타인적인 의미에서) 언어의 관습적이고 자의적인 의미 형성과 지시 관계를 어긋내며 시가 새로운 가상성의 세계를 작동시키기 시작한다고 말할 수 있다면, 안무는 도시 질서와 결속된 몸의 관습적인 움직임을 어긋내며 새로운 공간을 창출한다. “계속 움직여라.” 그리고 “계속 열중해서 걸어라.”10 혹은, 리듬을 어긋내라.

한 남자가 걷는 모습에서 좌우 다리만을 잘라 한 화면에 몽타주하여 기괴한 걷기를 보여주는 함정식의 터벅터벅(2010), 여러 사람이 몇 시간 동안 음악과 함께 초속경 시멘트를 발로 반죽하는 파트타임스위트의 행진댄스(2011), ‘완전 중립’이라는 문구가 적힌 바지와 이런저런 물건들을 수레에 묶어 서울의 중심부 시내를 며칠간 걸어다닌 김나영&그레고리 마스의 사건의 연속_완전 중립(2011), 구체적이고 고정된 것으로부터 가능한 멀리 나아가는 실험인 김소라의 추상적으로 걷다-한 지점으로부터 점차 물어지는 나선형의 운동(2012), 가상현실에서 비무장지대(DMZ)를 배회하는 걸음을 소리로만 암시하는 권하윤의 489년(2015-2016), 발의 크기가 다른 두 남녀가 각자의 발 크기만큼 걸음을 옮겨나가며 점점 서로간의 격차가 벌어져만 가는 모습을 담은 김민정의 100ft(2017), ‘함께하기’를 탐구한 프로젝트 How to Move the House(2019)의 출판물 부록에 협업을 위한 걷기를 안무화한 손혜민의 드로잉, 비장애인 중심의 보행 공간으로 형성된 도시에서의 장애인의 걷기에 관한 리슨투더시티의 거리의 질감(2023). 걷기와 직접적으로 관련했다고 여겨지는 미술 작업을 근과거의 기억에서 슬며시 꺼내기 시작하니, 또 여러 장면과 형상이 스치듯 떠오른다. 일상적 유속과는 확연히 구분되는 느린 움직임으로 도시 공간의 장소들을 걸어가는 차이밍 량의 행자(2016) 속 이강생, 와트가 동서남북 네 방향을 온 신체로 바라보며 (현실화하기 불가능한) 걷기로 이동하는 베케트의 『와트(Watt)』 속 한 장면, 하염없이 대지를 걷는 프란시스 알리스와 피를 뿌리며 걷는 레지나 호세 갈린도, 도시의 바닥을 수평으로 가로질러 끊임없이 기어가는 윌리엄 포프엘, 언어와 어긋나고 언어로부터 굴절된 몸의 수행을 보여주는 브루스 나우만의 형상들이 또한 얽혀 들어간다.

이 목록, 아니 이렇게 직조된 그물은 무엇일까? 이것은 표면적으로는 걷기와 관련된 것이지만, 보다 내밀하게는 걷기를 도입함으로써 정치를 발생시키는 예술적 실천이라는 직물의 한 조각이다. 다시 처음의 제목으로, 폴린 부드리/레나테 로렌츠가 제안하는 “다 함께 거꾸로 움직여 봅시다”로 돌아가 보자. 우리는 여기서 ‘거꾸로’를 ‘뒤로’로 해석할 수도 있으며, 리듬의 관점에서라면 역전된 진동의 파형을 떠올려 볼 수도 있다. 그러면 그것은 특정한 리듬이 구축했던 질서의 바깥을 제 몸으로 가지는 새로운 영역을 구축한다. 걷기를 다시 상상하는 일, 안무된 걷기의 정치는 리듬을 어긋내고, 파괴하고, 변형하고, 그리고 다시 발명하는 과정에서 발생한다. 걸음은 흔적을 남긴다.

“Let’s collectively move backwards”1

Richard Long kept walking back and forth along a virtual line, across a field in Wiltshire. The grass that his feet tread was broken and trampled over, creating gradated shades. A Line Made by Walking (1967) is a photographic production of this process, in which a clear line is stationed at the center of the landscape. Without being privy to this background story, however, viewers can readily recognize the photograph’s gesture to a certain movement that is ‘now absent,’ yet was ‘there at the moment.’ This is so, because a long straight line is an artificially created trace that stands apart from all other elements within the landscape. Walking leave traces. Tim Ingold asserts that our own kind’s cultural activities, such as walking, weaving, lathing, storytelling, singing, and writing share the tendency of linearity. He goes on to categorize lines into two types – threads, and traces. The trace “is any enduring mark left in or on a solid surface by a continuous movement,” which is usually being either additive or reductive.2 The additive would for instance involve a pencil layering graphite onto paper in the process of drawing a line, whereas the reductive would be more like chipping stone with sharp implements. Maintaining that A Line Made by Walking is neither additive nor reductive, Ingold explains how Richard Long’s treads simply step on the grass without either adding or taking away anything, allowing for an ephemeral line to emerge from the light shed on the trace. While Ingold’s descriptive classification may seem rather persistent, his approach shan’t be seen as a mere expression of adherent taxology. Rather, that which deserves attention is the diversity of the liminal traces in between the additive or reductive, or in other words the imagination that propels conjecture on the dynamic and the subsequent emergence of infinite modalities in transformation. To speak of the politics of choreographed walking, there must be an exploration of an epistemology relating to this imagination. Choreographed walking transfigures rhythm, which may not always leave visible trace. To rephrase: walking leaves trace.

Walking, on the other hand, is already trace in and of itself. ‘As such,’ or because it could seem like too trivial an occasion, walking may appear undeserving of inquiry or investigation. Still, even this excessively natural act is the product of the dynamic between an individual and the social, cultural forces they live by. Marcel Mauss conceptualizes this inter-dynamic as the techniques of body (les techniques du corps): a traditional way wherethrough people mobilize their bodies in disparate social communities. Illuminating how certain gestures deemed natural in a given society or culture are in fact intentionally engineered artifacts by observing the application of bodies in various cultures, Mauss introduces Elsdon Best’s description of the Māori’s women’s traditional mode of walking, called onioi which involves swaying one’s hips side to side. According to Best, this mode of walking is ‘drilled in.’ Bodily techniques are ‘gymnastics,’ cultivated in a given period. Asserting that education and imitation is key to the techniques of body, Mauss notes that “the action is imposed from without, from above, even if it is an exclusively biological action, involving his body. The individual borrows the series of movements which constitute it from the action executed in front of him or with him by others. It is precisely this notion of the prestige of the person who performs the ordered, authorized, tested action vis-à-vis the imitating individual that contains all the social element the imitative action which follows contains the psychological element and the biological element.”3 The techniques of body, as ‘effective traditional acts,’ are transmitted across bodies. As is the case with most transmissions, said acts are transformed for varied reasons. Generations born into touchscreen technology use their thumbs to press keys, for instance, whereas those who grew up in the analogue age still employ their index fingers even with smartphones as if maneuvering a computer keyboard. Most techniques of body continue to emerge and morph, but what remains constant is the fact that they are invariably formed, and constructed.

We may apply Mauss’s ideas about the transmission and transmogrification of techniques of body to the domain of rhythm. Rhythm pertains to the invention of order. We perceive rhythm upon noticing regular, repetitive patterns in a given flow. Meanwhile, such repeated patterns generate rhythms. Rhythms endow the world with and thereby reproduce order, and repetition is a prerequisite for the transmission and transmogrification of corporeal techniques. That which does not repeat itself, disappears. Or in other words, the body remembers a certain rhythm by instantiating that which is repeated. Henri Lefebvre, who is credited as the father of rhythm analysis, constantly emphasizes the import of the body by asserting as follows: “The body consists of a bundle (paquet) of rhythms, different but in tune…The body produces a garland (grebe) of rhythms, one could say a bouquet of rhythms.” 4 According to Lefebvre, the body is a bouquet of countless rhythms, and establishes relationships with various rhythms. He categorizes the modalities of this relationship into Isorhythmia, Eurhythmia, Polyrhythmia, and Arrhythmia, which carries a political implication. Isorhythmia is exemplified in how a conductor’s leading rhythm goes on to enlist other members of the orchestra, whereas Polyrhythmia and Eurhythmia assumes the “composition of diverse rhythms” and “the association of different rhythms,” respectively. Arrhythmia, meanwhile, involves the ‘desynchronization’ of rhythms. Lefebvre extends his dynamics of rhythms to claim a model of social dynamics by analogizing alliances as a kind of Eurhythmia, and struggles as Arrhythmia.5

Among the four, Arrhythmia is the kind that comes to the fore in relation to choreographed walking. Upon the disruption of the harmonious choreography of walking within regulated daily patterns arrives “suffering, a pathological state…The discordance of rhythms brings previously eurhythmic organisations towards fatal disorder.”6 Arrythmia, in which order is shattered to give way to a pathological state, may carry negative implications within our conventional morals. Should we take on a more critical stance toward the hegemonic rhythm of capitalism in our daily dealings, however, the kind of stability that combines and harmonizes the rhythms ensuing from the fictionality of capitalism becomes a target of sublation. In turn, the disruptive force of arrhythmia could signal the potential to create new time and space, and thereby form a new subjectivity. Considering rhythm as an ontology and epistemology could be the starting point of securing the path toward a more agential relationship between the ‘self’ and exogenous rhythms. Refusing to accept that which is immanently endowed upon the self as natural, embracing the pathological, and walking, differently. This attitude resonates with the critical motivation behind Michel de Certeau’s project of exploring ‘quotidian practice.’ de Certeau’s exploration of quotidian practice refers to the use of productions in ways that digress from the enforced manners of economic hegemonies, or in other words, investigating the proactive reproductions of consumers that disrupt the rhythm. This act may also be seen as countlessly diverse modalities of vacillations that are stationed between the two extremities of acceptance and resistance. Claiming that this strategy of reappropriation creates new spaces, de Certeau emphasizes that “consumers move with a techno-bureaucratically constructed and expressed, functionally created space. Their path within said space, however, generates unpredictable sentences, partially illegible ‘shortcuts.’ Despite comprising idiomatic diction and conventional syntax, the consumers’ trails sketch out disparate machinations of interests and desires. This machination is neither determined nor identified by the system through which the trails unfold.”7

Walking is one of Certeau’s important ‘quotidian practices.’ Or rather, those who walk are quotidian practitioners of the urban landscape. What deserves scrutiny here is that he sees walking as the equivalent of linguistic acts. To rephrase, de Certeau sees walking as a kind of ‘utterance,’ because the pedestrian concretizes spatial order. The pedestrian can subscribe to, or transform existing orders. If they stay away from blocked roads, then the roads in question become prohibited paths; if they choose to venture in despite instructions to the contrary, then the roads become new access ways. It’s performativity of walking. Seeing walking as a kind of rhetoric, de Certeau also goes on to analogize gestures to figure. How a pedestrian walks “distorts and fragments the city, prompting it to divulge from immutable order.”8 Here, we might invoke the interrelation between Yvonne Rainer’s choreography and poetry. Take, for instance, his poem “Walking in the City”:

Walking in the City

Yvonne Rainer

I can still love this time of day

east from Chelsea

south to St. Marks

a toothless moon

clearing the autumnal towers

each aglow in the sun’s spent light

As long as I can pass tatoo parlors palm readers, Greek lunchenettes, bodegas

there may still be room to breathe

in this devouring town

Keep Moving.9

In this poem, Yvonne Rainer choreographs the act of the subject who walks in the city. He is not devising any unique movement. In search of “room to breathe” in the urban space, the poetic narrator paces their step, roving the streets in crisscross pattern. The line of utmost significance in the poem is the concluding dictate, to “keep moving.” If we were to see poetry as mobilizing a world of new virtuality by fracturing the conventional and arbitrary semantics and semiotics of language (in the Wittgensteinian sense), choreography creates new space by displacing the conventional movements of the body, unbinding it from the urban order. “Keep moving.” And “keep walking, intently.”10 Or, off the rhythm.

Jeong Sik Ham’s Turbuk Turbuk (2010), which presents a strangely stylized walk through a montage of a striding man’s disembodied legs; Collective Part-time Suite’s Parade Dance (2011), wherein a group of people mix high early strength cement concrete with their feet for hours with music playing in the background; Nayoungim & Gregory Maass’s Spiral of Events_Extremely Neutral (2011), in which the artists walk around downtown Seoul wearing pants with the phrase “extremely neutral” inscribed onto it, dragging a cart full of sundry objects; Sora Kim’s Abstract Walking - A spiral movement gradually distancing from a single point(2012), an experiment that goes as far as possible from the concrete and fixed; Hayoun Kwon’s 489 Years (2015-2016), an artwork that acoustically gestures to footsteps wandering through the DMZ in a virtual reality environment; Minjung Kim’s 100ft (2017), showing the growing distance between a man and a woman, treading on in pace with their disparate foot sizes; Hyemin Son’s drawing, representing choreographed walking for the collaboration in the appendix of the publication project How to Move the House (2019) which exploring ‘To be together’ project; and Listen to the City’s Texture of Street (2023), a work about the walking of the disabled in a city built around able-bodied pedestrians. Reflections on artworks that directly relate to walking begin to be taken out of memories of the past, various the scenes and figures come to mind. The figures of Lee Kang-Sheng in Tsai Ming-liang’s Walker (2012), who walks through urban spaces with slow movement distinct from the place of daily urban life; a scene from Beckett’s Watt, describing a walk toward the east (in a way that cannot be readily realized), facing all four directions with the entirety of the body; or visions of Francis Alys striding across a vast stretch of land; Regina José Galindo sprinkling blood in the wake of her steps; William Pope. L crawling over an endless expanse of the horizontal urban floor; and Bruce Nauman showing the body performed against language and refracted it, are also intertwined.

What is this list – or rather, thus woven net? Superficially pointing to the act of walking, it is nevertheless a piece of fabric called artistic practice, which engenders politics by secretly implementing walking. Let us return to this essay’s title, per Pauline Boudry/Renate Lorenz’s suggestion – “Let’s collectively move backwards.” Here, we may interpret ‘backwards’ as ‘toward the rear,’ or think of inverse vibrations from a rhythmic perspective. Then, it builds a new realm, enlisting the exteriority of the order that a given rhythm had constituted. Reimagining walking, the politics of choreographed walking emerges from the process of disrupting, destroying, transforming, and reinventing rhythms. All Walking leave traces.

-

이 제목은 2019년 베니스비엔날레 스위스관에서 폴린 부드리/레나테 로렌츠의 거꾸로 움직이기(2019)와 함께 발행된 문서에서 관객에게 보내는 편지 형식으로 쓴 작가의 글에 등장하는 표현에서 가져왔다. 부드리/로렌츠는 정상성의 규범이 강요되고 혐오가 만연한 사회적 현실을 비판하며, 진보라는 환상에 거울을 비추듯 “다 함께 거꾸로 움직여 봅시다.”라고 제안한다. 이들은 쿠르드족 게릴라 여성들이 눈 덮인 산악 지대에서 이동할 때 신발을 거꾸로 신고 걸은 것을 작업의 모티프로 삼은 것을 밝히며 다음과 같이 말한다. “우리는 이 움직임의 전술적 양면성을 사람들이 함께 모이고, 우리의 욕망을 재구성하고, 자유를 행사하는 방법을 찾는 수단으로 사용할 수 있을까요? 이 움직임이 후퇴가 진보의 불가피성이라는 개념에 대항할 수 있을까요? 우리는 거꾸로 이동하며 사랑받는 이들뿐 아니라, 사랑받지 못하는 존재들과도 함께 살아가는 방식에 대해 생각할 것입니다. 우리는 거꾸로 움직일 것입니다. 이 기이한 조우가 예기치 않은 일이 일어나기 위한 유쾌한 출발점이 될 수 있기 때문이죠.” Step x Step(2023)을 통해 이 작품을 선보인 코리아나미술관에서 한국어 번역본을 관객에게 제공하였다.

This title gestures to the writers’ epistolary address to the readers in the document issued alongside Pauline Boudry/Renate Lorenz’s Moving Backwards (2019), showcased at the 2019 Venice Biennale’s Switzerland Pavilion. Critiquing the social reality in which hate prevails amidst enforced normality, Boudry/Lorenz proposes that we all “move backwards,” as if presenting a mirrored image of progress with respect to its illusive ideal. Noting how they drew inspiration from woman in the Kurdish guerilla movement who wears their shoes backwards when moving across snowed-in mountainous terrain, they say: “Can we use the tactical ambivalence of this movement as a means of coming together, re-organizing our desires, and finding ways of exercising freedoms? Can its feigned backwardness even fight the notion of progress’s inevitability? We will move backwards and think about the ways in which we wish to live with loved but also unloved others. We will move backwards, because strange encounters might be a pleasant starting point for something unforeseen to happen.” Coreana Museum of Art, which presented this work through Step X Step (2023), offers a Korean translation to the audience. ↩ ↩ -

마르셀 모스 지음, 몸 테크닉, 박정호 옮김, 파이돈, 2023, 82쪽.

Mauss, Marcel. Les Techniques du corps. Trans. Jeungho Park. Python, 2023: 82. ↩ ↩ -

앙리 르페브르 지음,리듬 분석, 정기헌 옮김, 갈무리, 2013, 89쪽.

Lefebvre, Henri. Elements de rythmanalyse. Trans. Kihyun Jeong. Galmuri, 2013: 89. ↩ ↩ -

미셸 드 세르토 지음, 일상의 발명: 실행의 기예, 신지은 옮김, 문학동네, 2023, 51-52쪽.

de Certeau, Michel. L’invention du quotidien: vol. 1., Arts de faire. Trans. Jieun Shin, Munhakdongnae, 2023: 51-52. ↩ ↩ -

“계속 열중해서 걸어라(Keep walking intently)”는 플럭서스와 관련 있었던 작가 타케히사 고수기의 극장 음악(1963)을 관통하는 스코어이다. 극장 음악은 플럭서스가 발행한 신문인 cc VTRE의 1964년 2월호에 인쇄되었는데, “계속 열중해서 걸어라”라는 문구는 마키우스나스가 디자인한 것으로 알려진 나선형으로 구축된 발 모양의 그림과 함께 놓여 있다. 걸음을 “열중해서” 걸으라는 요구는 일견 단순해 보이지만, “계속 움직여라”라는 주문처럼 전혀 다르 움직임과 관계의 가능성을 여는 안무적 장치가 될 수 있다. 자세한 내용은 다음을 보라; Lori Waxman, Keep Walking Intently: The Ambulatory Art of the Surrealists, the Situationis International, and Fluxus, Sternberg Press, 2017.

“Keep walking intently” is a score that flows through the Fluxus Movement-associated writer Takehisa Kosugi’s Theatre Music (1963). Theatre Music was printed in the February issue of cc VTRE in 1964, a newspaper issued by Fluxus. The phrase “keeping walking, intently” is placed alongside a spiral-shaped sketch in the shape of a foot, known to be designed by Maciunas. The demand to walk “intently,” belying its simplicity, could serve as a choreographic device that opens up the possibility of completely new movements and relationships – like the dictate to “keep moving.” See the following for more details: Waxman, Lori. Keep Walking Intently: The Ambulatory Art of the Surrealists, the Situationis International, and Fluxus, Sternberg Press, 2017. ↩ ↩