이야기 만들기: 새로운 지식을 위한 배움의 도구와 미술관

about

서울시립 북서울미술관에서 진행된 국제 심포지엄. 미술관에서의 배움과 지식 생산의 문제를 논의하기 위한 주제로 ‘이야기’를 다루었다. 프란스할스미술관(네덜란드), 아시아아트아카이브(홍콩), 류블랴냐현대미술관(슬로베니아), 굿스쿨(인도네시아), 개러지현대미술관(러시아), 카스코 아트 인스티튜트: 공동을 향하여(네덜란드) 등 총 6개의 해외 기관이 참여해 발표와 토론을 진행했다.

curatorial

미술관은 배움의 장소가 될 수 있는가?

이야기 만들기: 새로운 지식을 위한 배움의 도구와 미술관은 미술관이 오늘날 우리에게 필요한 내용과 형태의 지식, 대안적 사고와 행동을 생산하고 순환시키기 위한 ‘방법’은 무엇인지 묻기 위해 기획되었다. 방법이라는 용어의 사용은 여기서 논의하는 지식이라는 것이 특수한 대상임을 전제한다. 이에 이번 행사에는 자기 자신이 놓인 현재에 대한 역사적, 사회적, 문화적, 정치적 문제의식을 기반으로 미술관이 지식 생산 주체로서 무엇을 어떻게 수행해야 하는지에 대해 고민하고 나름의 길을 만들어 온 여섯 기관을 초대했다. 이야기 만들기: 새로운 지식을 위한 배움의 도구와 미술관은 이들의 구체적인 실천 사례와 그 실천을 통해 구체화되는 미술관의 비전을 나란히 놓아 보고, 참여자들 서로 간의 동형적인 것 안에서 이질적인 것을 발견하고 동질적인 것 안에서 동형적이지 않은 것을 살펴보고자 한다. 섣불리 합의에 다가서려 하기 보다는, 대화를 위한 목소리를 듣고 우정의 윤리에 기반한 네트워크를 상상한다. 이를 위해 각자의 방법이 만나고 갈라지는 하나의 공통된 지평을 만들어 봄으로써, 과연 우리들의 미술관은 현재를 어떻게 인식하고 어디로 나아가야 할지를 논의하고자 한다.

미술관에서의 지식 생산과 순환이라는 주제에 대하여 이번 심포지엄은 ‘이야기’라는 이름의 문을 열고 들어간다. 여기서 다루는 ‘이야기’에 대한 정의는 구조주의 서사학의 이론적인 틀을 참고한다. 구조주의자들은 서사물이 ‘이야기’와 ‘담론’으로 구성되어 있다고 여긴다. 이야기는 등장인물, 구체적인 배경, 행위 등 사건적 요소와 사물적 요소들이 합쳐진 것이며 담론은 이야기를 전달하는 방식을 일컫는다. 중요한 것은, 구조주의 서사학은 이야기와 담론의 통합적인 작용을 통해 하나의 서사물이 의미를 내포하게 되고 특정한 문학성을 발생시킬 수 있다고 여긴다는 것이다. “맥베드를 위대한 문학으로 만드는 것은 무엇인가가 아니라 그것을 비극으로 만든 것은 무엇인가” 라는 질문이 시학이 다루는 문제라고 정의하는 비평가 시모어 채트먼(Seymour Chatman)의 말을 곱씹어 본다면, 미술관에서의 지식 생산과 순환이라는 주제를 다루기 위해 ‘이야기’라는 개념을 도입한 목적은 보다 분명해질 수 있다. 미술관이 작품과 아카이브, 관객과 미술관의 공간 등 자신이 가진 자원을 어떻게 배치하여 이야기를 만들고 그것을 어떻게 발화하는지를 살피고, 이러한 배치에서 발생한 잉여의 가치, 즉 개별 작품을 초과하는 가치를 지식이라는 이름으로 명명하기 위한 것이다. 그 가치가 수행적인 힘을 가지게 되고 네트워크를 형성할 수 있다면 우리는 비로소 ‘배움’이라는 과정을 일종의 지도처럼 펼쳐놓을 수 있을 것이다. 다소간의 비약을 감수한 이와 같은 이론적 절충주의를 통해 우리는 지식이라는 모호한 형상에 구체성을 부여하고, 미술관이 수행하는 배치와 재배치의 행위를 다루는 것에 대한 명확한 관점을 부여한다.

논의를 위한 개념적 범주의 설정 외에도, ‘이야기’가 이번 심포지엄의 기획에 있어서 중요하게 다루어지는 두 가지 이유가 더 있다.

첫 번째는 이야기의 유동성과 상호성이다. 이야기란 하나의 구조화된 사건이지만, 이야기 자체는 결코 정형화되지 않는다. 이 가변성은 개개인의 ‘기억하기’의 문제와 깊이 관련되는 한편, 보여주는 사람과 보는 사람, 말하는 사람과 듣는 사람이라는 연속적인 관계 속에서 또한 발생한다. 이야기를 보고 들은 사람이 곧 이야기를 쓰고 말하는 사람이 되기도 한다는 점에서 이야기는 무엇보다도 순환과 전이를 통해 형성되는 것이다. 생산과 수용이 일방적 위계를 가지는 것이 아니라 특정 형태의 관계를 통해 이루어진다는 점은, 오늘날의 미술관이 관객을 적극적인 의미 생산자로 여기는 것과 긴밀히 연동된다.

두 번째는 이야기라는 것이 일종의 허구라는 점이다. ‘탈-진실’이라는 진단은 객관적인 사실이 상실된 오늘날의 세계상에 대한 경계이기도 하지만, 한편으로 그것은 이 시대가 결여한 윤리, 비가시적인 주변부의 현실과 지금 여기가 아닌 다른 세계에 대한 탐색 장소로서의 허구의 힘이 약화된 것을 알리기도 한다. 전 지구적으로 모든 삶이 자본이라는 하나의 모델로 통합되고 있는 지금 우리에게 필요한 것은 현실을 첨예하게 인식하는, 누락된 주체를 호명하고 현실의 재구성을 실험하는 방법으로서의 허구이다. 이러한 맥락에서 오늘날의 미술관이 다루어야 하는 대표적인 허구는 역사와 공동(common)이라는 이름을 가졌다. 이것은 자기 자신을 어떻게 규정할 것인지, 그리고 자기 자신이 포함된 세계의 구성원(사물을 포함한)을 어떤 질서로 관계 지을 것인지를 묻는 일이다. 이번 심포지엄의 두 세션은 이러한 문제의식에서 비롯된 것이라고 할 수 있을 것이다.

하지만 여기에는 우리가 분명 짚고 넘어가야 할 피할 수 없는 질문이 있다. 왜 미술관이 배움의 장소로서 특권적일 수 있는가? 말하자면, 왜 역사를 역사학에, 공동의 구성을 현실정치에 위임하지 않고 미술관에서 다루어야 하는가? 보다 넓게는, 미술관이 대학교나 여러 대안적 교육 기관, 심지어 유튜브에 비해서 어떻게 비교우위를 가지는가? 이 질문은 기본적으로 경제적 논리에 기반한 것이며 미술관에 종사하는 관계자라면 다소 부당하다고 느낄 수 있지만, 냉정하게 받아들이고 명료하게 설득이 필요한 문제다. 이에 대답할 수 없다면 이 심포지엄 자체가 돌연 공허한 것으로, 그리고 사회적인 제도로서의 미술관의 존재 당위가 공공연히 의심받을 수밖에 없을 것이다.

나는 미술관이 가진 고유한 자원인 소장품과 아카이브, 그리고 관객에 있으며, 그것을 전시, 연구, 출판 등의 도구를 사용해 어떻게 매개하고 재생산하는 지에서 그 대답을 찾을 수 있다고 생각한다. 이는 미술관의 자원이 시대와 관계를 맺는 고유한 텍스트로서 중요한 가치를 지녔으며 이러한 텍스트와 결합한 재생산의 형식이 특수한 지식을 만들어 낼 수 있다는 믿음에 기반한다. 그리고 이 믿음은 이번 심포지엄에 초대된 6개의 기관이 암묵적으로 공유하는 가치이기도 할 것이다. 우리는 구체적인 실천들에서 설득의 근거를 찾을 수밖에 없다. 따라서 이번 심포지엄에서는 이들이 자기 자신의 믿음을 어떻게 전개하는지를 구체적으로 살펴보고, 그 시간 속에서 이루어진 여러 중요한 선택들에 관해 다양한 맥락 위에서 대화하고자 한다.

심포지엄의 첫 번째 세션은 아카이브와 소장품을 다룬다. 미술관이 보유한 소장품과 아카이브는 미술관 스스로의 정체성을 만들기 위한 중요한 재료다. 그리고 소장품과 아카이브에 관한 연구는 미술 작품의 당대적인 해석을 통해 그 가치를 규범화하는 사고방식과 언어를 공공에 제안한다. 그 언어는 미술의 개념을 제도적인 차원에서 재조정하고 미술관이 추구하는 가치를 보여주며, 나아가 새로운 미술사를 쓰기 위한 초석이 된다.

네덜란드 하를럼에 위치한 프란스할스미술관은 역사상 이 지역에서 가장 유명한 17세기 작가인 프란스 할스의 많은 작품을 보존하고 전시한다. 뿐만 아니라 동시대 비디오 작품을 또한 중점적으로 수집하는데, 이에 미술관은 ‘초역사적 미술관(transhistorical museum)’이라는 방법론으로 소장품에 대한 새로운 접근을 시도한다. 프란스할스미술관은 벨기에 루뱅(Leuven)에 위치한 M 미술관(Museum Leuven)과의 협업으로 초역사적 미술관에 대한 이론적 논의를 주도하는 한편, 전시를 통해 다양한 시대를 병치시키며 당대의 시각문화의 맥락에서 유효하게 논의할 수 있는 주제들을 찾아내고 설명한다. 고전 작품에 대한 새로운 해석 방식을 제안함으로써 생겨난 미술관의 새로운 정체성은 미술관이 운영하는 다양한 프로그램 및 관객과의 관계 맺기 방식에도 큰 영향을 준다. 한편 아시아 아트 아카이브와 류블랴나현대미술관은 각각 아시아와 동유럽이라는 미술관이 위치한 지역적 특수성에 대한 문제의식을 미술관 비전의 근간에 둔다. 홍콩의 아시아 아트 아카이브의 아카이브 컬렉션은 기본적으로 공공에 개방되어 있으며, 아시아 현대미술에 관한 역사 서술 및 교육 자료로 사용된다. 2009년 만들어진 교육∙참여팀은 홍콩의 미술 교과과정 개편 과정에서 현대미술에 대한 학습 자료와 현장 교사들의 낮은 이해도에 관한 문제의식에서 만들어진 것으로, 아카이브 자료를 통한 아시아 미술 연구를 기반으로 공공교육을 지원하는 프로그램 티칭 랩을 운영한다. 이러한 지식 생산과 배움의 과정을 통해 티칭 랩은 학생들이 홍콩의 사회, 문화적 조건과 삶의 문제를 통합적으로 사고할 수 있도록 이끈다. 슬로베니아는 1991년 유고슬라비아에서 독립하였으며, 류블랴냐현대미술관은 국가의 주요한 동시대 미술관의 기능을 수행한다. 류블랴나현대미술관은 지난 20년간 동유럽의 역사에 관한 연구를 중점적으로 이어 왔는데, 특히 미술관의 《아트이스트 2000+》 컬렉션은 동유럽 지역의 아방가르드 예술을 초국가적 차원에서 맥락화시키기 위한 기본적인 자원이다. 이번 심포지엄에서는 이와 같은 미술관의 비전 아래 유럽 지역 미술관들의 국제적 네트워크인 랭테르나시오날(L‘Internationale)의 일원으로서의 활동과, 동유럽 지역의 역사를 비동맹 네트워크와의 관계 속에서 새롭게 성찰한 최근의 전시 ⟪남쪽의 성좌들: 비동맹의 시학(Southern Constellations: Poetics of the Non-Aligned)⟫에 대해 소개한다. 또한 2000년대 진행되었던 《급진적 교육(Radical Education)》 프로젝트의 유산과 사회주의 체제를 공유했던 문화가 오늘날 미술관 모델을 구축하는데 어떻게 남겨졌는지를 다룰 것이다.

두 번째 세션은 미술관이 어떻게 지역 사회에 개입하며 새로운 형태의 공동체를 구성하기 위한 교점 역할을 하는지, 혹은 어떤 개입의 장소가 되어야 하는지를 다룬다. 이를 위해 우리는 관객의 신체에 대해 ‘몸짓’이라는 관점으로 접근한다. 한 개인의 몸에는 개인이 속한 사회의 규범과 문화적인 기억이 각인되어 있다. 이는 몸짓이라는 구체적인 양식으로 드러나고, 이를 통해 끊임없이 재생산된다. 이러한 맥락에서, 신체에 다른 몸짓을 부여하고 다르게 움직이기를 요구한다는 것은 바로 이와 같은 규범과 기억에 대한 대안을 상상하는 일이 된다. 그리고 이것은 한 개인에 국한된 문제일 뿐만 아니라 그 몸들이 놓일 장소와 몸짓들을 연결하는 방식의 문제, 즉 새로운 공동체의 개념 형성과도 긴밀히 이어진다. 미술관은 지역 사회 안에서 어떤 공동체를 만들어 나갈 것인지, 그 공동체의 구성원이 현재와 미래에 어떤 주체성을 획득해야 하는지를 상상하는 제도이다. 여기서 미술관은 일종의 매개자로서, 그리고 공동의 모델을 구축해보는 시험장으로 기능한다.

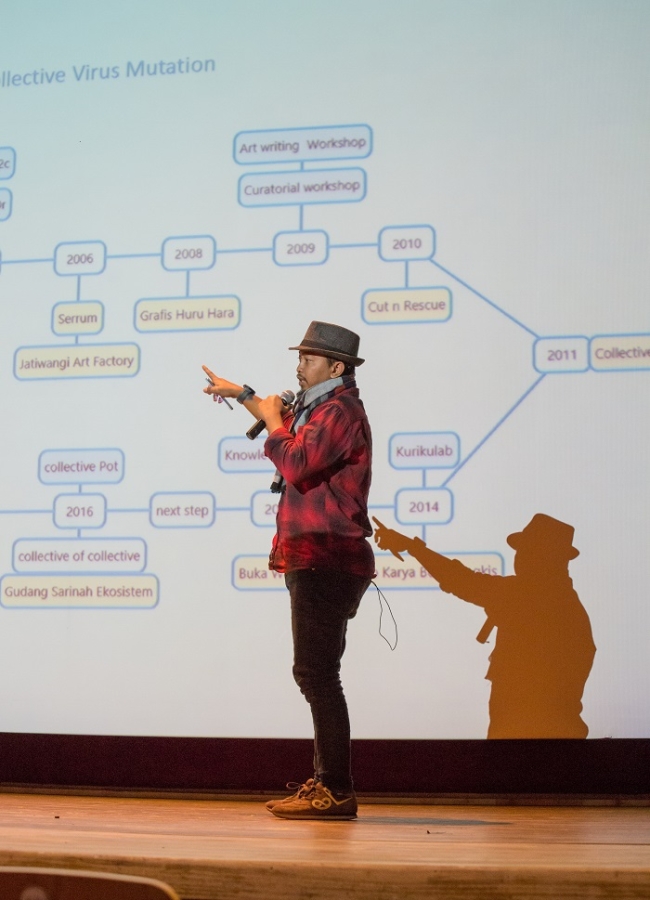

굿스쿨(Gudskul)은 인도네시아 자카르타 기반의 컬렉티브 루앙루파(Ruangrupa), 세럼(Serrum), 그라피스 후라 하라(Grafis Huru Hara)가 협력하여 설립한 배움의 공간이다. 굿스쿨의 주요한 구성 원리인 컬렉티브는 인도네시아의 현대사의 맥락에서 탄생한 주요한 예술 흐름이기도 하다. 특히 이러한 컬렉티브의 움직임은 예술 작품을 생산하는 것에 국한되지 않고 대중들과 함께하는 공공 프로그램 등의 활동을 통해 사회적으로 작동하고자 했으며, 이는 대안적인 것에 대한 요청이 아니라 그 스스로가 생태계를 구성할 필요성에 따른 것이었다. 수 년간의 과도기를 거쳐 2018년 설립된 ‘굿스쿨: 동시대 미술 컬렉티브 연구 및 생태계’는 자기 자신의 지역에서 요청되는 예술 실천과 교육을 수행하는 플랫폼이다. 굿스쿨은 이번 발표에서 그들이 농크롱(nongkrong)이라고 부르는 함께하기의 형태가 어떻게 배움의 장소가 되고 새로운 생태계를 형성하는 교점이 되는지 질문하고, 나아가 그것이 어떻게 지속할 수 있을지를 고민한다.

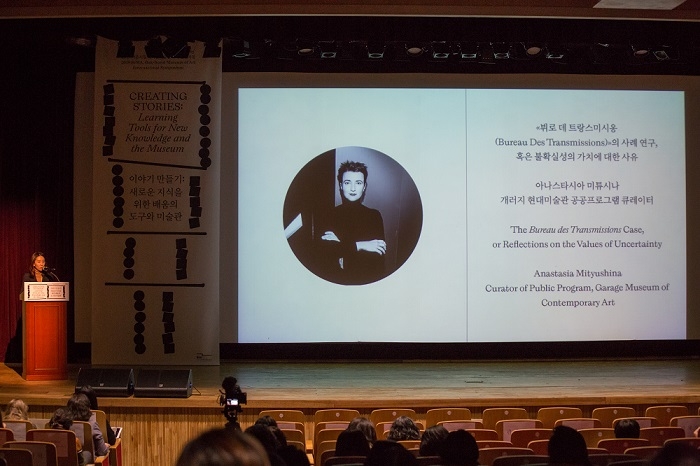

러시아 모스크바에 위치한 개러지현대미술관에서 최근 진행한 뷔르 드 트랑스미시옹(Bureau des Transmissions)은 미술관의 교육 및 공공프로그램 설립 10주년을 맞아 기획된 것으로, 미술관 교육의 가능성에 대해서 질문하고 그 이상과 실재 사이의 간극에 대해 고민하는 일종의 실험실이었다. 우리는 이번 심포지엄에서 뷔르 드 트랑스미시옹을 예시로 미술관 교육 프로그램의 현실적인 문제들을 비롯해 러시아의 맥락에서 미술관 교육은 어떤 의의를 가지는지, 미술관이 배움에 있어서 어떠한 장소가 되어야 하는지에 대해 살펴볼 수 있을 것이다. 그리고 여기에는 분명 미술관의 관객이 어떤 정치적 주체가 되어야 하는지, 어떤 구성 원리 속에서 다루어져야 하는지에 대한 숙고가 필요하다. 카스코 아트 인스티튜는 네덜란드 우트레흐트 지역에서 30년간 운영되어 왔으며, 불평등과 다양성, 기후변화 같은 현재 우리가 당면한 문제들에 대해 어떻게 예술이 공동을 구성할 수 있을 것인가 질문한다. 이에 지난 2018년 ‘카스코 아트 인스티튜트: 공동을 향하여’로 기관의 이름을 바꾸며 그 비전을 새로이 정비했다. 이들이 말하는 ‘커먼’이란 ‘공동체들의 자기 조직화로 만들어진 생태계 혹은 문화’로, 근본적으로는 사회적 변화를 의미한다. 커먼의 학교는 이 기관에서 진행되는 연간 프로그램이며 미술관의 벽을 넘어 다양한 활동을 진행한다. 이번 발표에서 로사 파르덴쿠퍼는 우트레흐트 지역의 버려진 테르비데 농장에서 진행했던 프로그램을 소개하며, 미술과 미술 기관이 어떻게 개입의 장소로서 공동을 만들어 나갈 수 있을지에 대한 질문을 공유한다.

오늘날 우리는 이미지가 넘쳐나는 시대에 살고 있다. 그것은 이미지를 주요하게 다루는 미술관 또한 예외가 아니다. 그런데 이런 반문이 있을 수 있다. 미술관에 이미지가 넘쳐나는 것이 무슨 문제가 되는가? 이미지라는 것 또한 특정 시대를 반영하는 특수한 구성물이니 말이다. 하지만 현재의 기술 환경과 경제 체제에서, 이미지의 생태계 속에서 특별한 인터페이스의 개입 없이는 우리에게 필요하고 숙고해야 할 이미지는 점점 더 비가시적이게 된다. 여기서 특별한 인터페이스란 시각문화에 대한 해석적 필터링을 뜻한다. 문화적 제도로서 이와 같은 인터페이스를 작동시키지 않는 미술관은 그저 이미지의 증권거래소가 될 뿐이며, 우리에게 주어지는 것은 소비의 대상으로 덩어리진 이미지이거나 무엇도 지시하지 않는 전광판의 숫자뿐일 것이다. 악화(惡化)가 양화(釀禍)를 구축한다. 미술관에서의 지식 생산과 순환에 관해 다루고자 할 때, 결국 우리는 이러한 질문과 마주칠 수밖에 없을 것이다. 우리에게는 어떤 이미지가 필요한가? 혹은, 우리는 어떤 이미지를 만들어야 하는가? 미술관은 점점 더, 바로 이 질문에 답하기 위한 일종의 실험실이 되어갈 것이다.

(이한범)

Can the Art Museum Become a Place of Learning?

Creating Stories: Learning Tools for New Knowledge and the Museum was envisioned to question what kind and form of knowledge we need today and the ‘methods’ through which to produce and circulate alternative thinking and action. The term ‘method’ is used here based on the understanding that ‘knowledge,’ in this context, is a very specific objective. Accordingly, this event invites six institutions, all of whom have paved their own way in defining the role of the art museum as a producer of knowledge based on the historical, social, cultural, and political awareness of their respective presents. Creating Stories: Learning Tools for New Knowledge and the Museum examines the case of each institution and their efforts in realizing their vision. In the process, it hopes to discover differences among commonalities and commonalities among differences shared by the institutions. Rather than making a premature consent, we want to hear a voice for conversation and to imagine a network based on the ethics of friendship. By creating a common ground where their methods intersect and diverge, the event hopes to discuss how our art museums can understand the present and find their direction into the future.

On exploring how knowledge can be produced and circulated through art museums, this symposium takes ‘stories’ as its starting point. The definition of ‘stories’ here references the theoretical framework of structuralist narratology, which understands that all narrative form consists of a ‘story’ and a ‘discourse.’ Story refers to the elements of events and materials, such as the characters, their background, and actions, while discourse, on the other hand, refers to the manner in which the story is delivered. What is important is that structuralist narratology acknowledges the integration of story and discourse as what gives the narrative form its meaning and literary value. If we remind ourselves of film and literary critic Seymour Chatman’s statement that “Poetics is not concerned with ‘What makes Macbeth great?’ but rather ‘What makes Macbeth a tragedy?,’” we can understand more clearly why the concept of ‘stories’ was chosen to examine the production and circulation of knowledge in art museums. In other words, by focusing on how a museum utilizes and translates its resources—including the collection, archive, exhibition space, and visitors—into stories and how those stories are told, we can identify the surplus value it creates beyond the value of individual artworks that we may define as knowledge. If we could imbue performativity to that value and create a network around it, we would be able to navigate the terrain of what we call the process of ‘learning.’ Through this theoretical eclecticism, we can give specific form to what we define as knowledge and gain a clear perspective on the act of arrangement and rearrangement implemented in museums.

In addition to providing the conceptual boundaries for discussion, ‘stories’ play an important role in this symposium for the following two reasons.

The first is the fluidity and reciprocity of stories. A story may be a structuralized narrative of an event, but the story itself cannot be standardized into any single form. This variability is deeply related to the essence of ‘memory,’ but it also emerges within the sequence of relationships between the person who shows and the one who sees, as much as the one who tells and the one who listens. The fact that the one who sees and listens can be the one who tells and writes the story allows the story to form through circulation and transference. Understanding that production and reception are not based on a hierarchical order but on a specific kind of relationship closely mirrors the relationship between museums and visitors today, where the visitors are regarded as active producers of meaning.

The second is the fact that stories are essentially a fiction. The term ‘post-truth’ may represent the state of the world today where objective truth is lost, but at the same time, it also reflects the weakening authority of fiction as a place to seek a world away from the here and now, this world that is devoid of morality and its harsh reality of the marginalized. Today, when people’s lives around the world are bounded by capitalism, what we need is a kind of fiction that acutely diagnoses our reality and serves as an outlet to experiment with the ways to reconstruct that reality. In this context, the best example of ‘fiction’ that museums must face today is the idea of history and the ‘common,’ as it requires the questioning of how one should define oneself, and the order through which one should engage with the rest of the world (including objects). The two sessions of this symposium stem from these very questions.

At the same time, there is a question we must inevitably face before going forward: How can the art museum justify its privileged position as a place of learning? In other words, instead of letting the historians deal with history and having the politicians deal with the idea of the common, why should an art museum take the initiative? More broadly, how can an art museum maintain its status over universities, educational institutions, or even YouTube? These issues may feel unjustified to anyone working in an art institution, but they are nevertheless based on economic logic and should be addressed and confronted with clarity. If we cannot respond to these concerns, this symposium itself would be meaningless, and the existence of art museums as a social institution would come into question.

I believe the answer to this question lies in the unique resources of each museum, including the collection, archives, and visitors. Moreover, it relies on how each institution mediates and reproduces its exhibitions, research, and publications as its tools. All of this is based on the belief that the resources of an art museum have value as a unique text that reflects its time, and by reproducing this text, we can achieve new knowledge. Most likely, it is a belief implicitly shared by all of the six institutions participating in this symposium. We can only find grounds for persuasion through specific actions, and therefore this symposium hopes to examine how each institution has translated this belief into action and to discuss some of the related key decisions in a wide range of contexts.

The first session of the symposium focuses on archives and collections—the core materials that form the identity of a museum. Research on the collection and archives provides contemporary interpretations of the artworks and communicates a way of thinking to the public, as well as language that defines its value. This language is what realigns the concept of art on an institutional level and reflects the values that the institution upholds. Furthermore, it becomes the very foundation on which new art history is written.

The Frans Hals Museum, located in Haarlem, the Netherlands, preserves and exhibits artworks by the region’s famous seventeenth-century master, Frans Hals. The museum also actively collects contemporary video art, which reflects a new approach to its collection as a ‘transhistorical museum.’ In close collaboration with M Leuven in Switzerland, the museum not only leads the way with its theoretical discussions on the concept of the transhistorical museum, but its exhibitions also juxtapose artworks from different time periods and explore subjects which lead to meaningful conversations on contemporary visual culture. The museum’s new identity, based on new interpretations of classic masterpieces, extends to various programs run by the institution and greatly affects its engagement with visitors. On the other hand, institutions such as Asia Art Archive (AAA) and the Moderna Galerija, Ljubljana focus on the specificity of their distinct locations as the core of their institutional vision. The archive collection of AAA in Hong Kong is open to the public and provides important historical and educational material on Asian contemporary art. In 2009, AAA established its Learning and Participation Department to provide educational materials on contemporary Asian art in accordance with Hong Kong’s art education curriculum reform and to address teachers’ need for their own education on the subject. The department offers the Teaching Labs program, which supports public education through its archive resources on contemporary Asian art. Through the process of learning and knowledge production, the Teaching Labs help students develop integrative thinking skills in facing the challenges of life, society, and cultural conditions in Hong Kong. Slovenia gained its independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, and since then, Moderna Galerija, Ljubljana has remained the country’s central institution for contemporary art. Over the past twenty years, the museum has consistently focused its research on the history of Eastern Europe, and its Arteast 2000+ collection offers fundamental resources in contextualizing the avant-garde art of Eastern Europe on a transnational level. In this symposium, the museum will introduce its institutional vision and how it is reflected in its activities as a member of L‘Internationale, an international network of regional art museums in Europe. Moreover, the museum will further discuss its recent exhibition Southern Constellations: Poetics of the Non-Aligned, which examines the history of Eastern Europe through the legacy of the Non-Aligned Movement, and its Radical Education Project from the 2000s to examine how Slovenia’s culture, rooted in its socialist past, has influenced the establishment of the current model of art institutions in the country.

The second session of the symposium will explore how museums can engage with local communities and become a focal point for creating new forms of community. The discussion will center on the physical body of the visitors, approaching the subject through the concept of ‘gestures.’ The body of an individual inevitably carries the social standards and cultural memory of the society it belongs to. These are expressed through gestures, and are endlessly reproduced. In this context, demanding that the body move differently and make different gestures would be imagining an alternative to the standards and memories imprinted on the body. Furthermore, it goes beyond the individual but concerns the ways of connecting those gestures and the places where the bodies are. In other words, it intimately connects to form a new concept of community. Museum could imagines what kind of subjectivity its members can claim in their present and future. Here, the museum serves as a mediator, and as a testing ground for constructing a new community model.

Gudskul is a place of learning established via a collaboration between three Jakarta-based collectives: Ruangrupa, Serrum, and Grafis Hura Hara. The founding concept of Gudskul, a ‘collective,’ is an important art trend that emerged in Indonesia in response to its long history of dictatorship. This trend of art collectives aims to go beyond the production of artworks, but more importantly to the development of public programs and activities that engage with the community. Their objective is not rooted in the need to find an alternative practice, but rather the necessity to create an independent ecosystem. After a long transitional period, in 2018 the collective launched Gudskul: Contemporary Art Collective and Ecosystem Studies, a platform for artistic practice and education catering to the needs of the local community. In this presentation, Gudskul asks how the form of ‘together’ they call “nongkrong” is the learning place and the node for forming a new ecosystem. The Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, located in Moscow, Russia, celebrated its tenth anniversary of education and public programs with Bureau des Transmissions, an experimental project which explores the possibilities of art education and contemplates the inevitable gap between reality and ideals in its practice. In this symposium, Bureau de Transmissions is examined as a case study through which we can discuss the challenges of implementing art education programs in museums and question what kind of place a museum should be as a place of learning. The discussion will further focus on what kind of political entity a museum should strive to be, and what guiding principles the institution must follow. Casco Art Institute has been run in the Utrecht region of the Netherlands for 30 years, and asks how art can form the common against problems we face now, such as inequality, diversity, climate change, etc. In 2018, the institution changed its name to Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons and renewed its vision. They say that the ‘common’ is “an ecosystem or culture created by the self-organized communities, and it basically means social change.” School in Common is an annual program by the institution that runs beyond the four walls of the museum. In this presentation, Casco Art Institution introduces a program on the abandoned Terwijde farm in Utrecht and shares questions about how art and art institutions can intervene and create the common.

The era we live in is one overflowing with images. The same can be said of art museums, as they are institutions governed by images. On the other hand, we can also ask ourselves: Is an overflow of images in art museums really a problem? Images and their ecosystems are texts that reflect their time. In the current technical development and economic system we live in, however, the images that matter—the thought-provoking and the meaningful—will continue to diminish unless a special interface intervenes in the ecosystem of images. Here, ‘special interface’ refers to the interpretive filtering of visual culture. As cultural institutions, if museums do not activate this ‘interface,’ it will be no different from being a stock exchange of images. Then, the only images we are left with will be those that serve as the object of consumption and meaningless numbers on a billboard. “Bad money drives out the good.” As we probe into the issues of knowledge production and circulation in art museums, we will inevitably be faced with the following questions: What kind of images do we truly need? What kind of images should we create? More and more, the art museum will become the laboratory we need to find the answers to these questions.

Hanbum lee