텅 빈 캔버스를 돌아 나오며

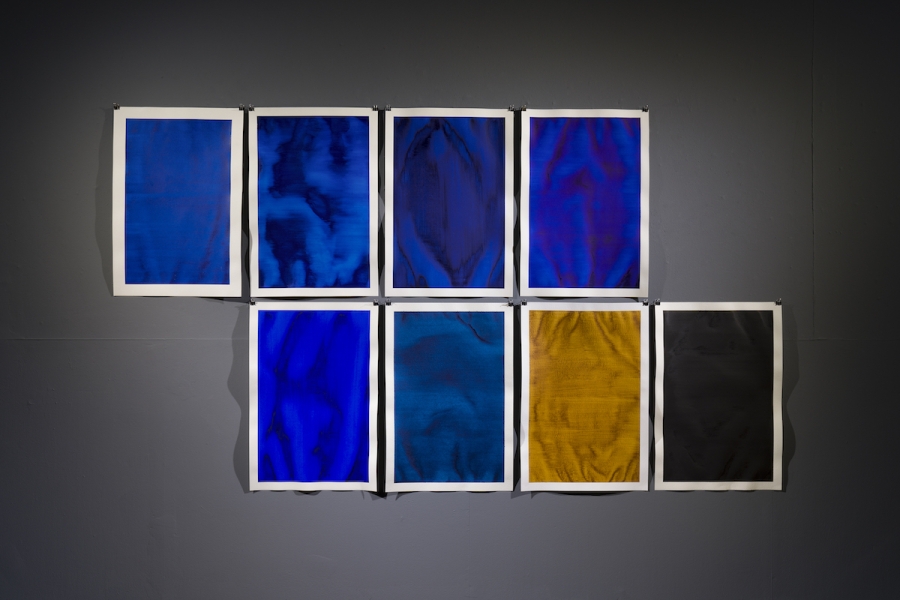

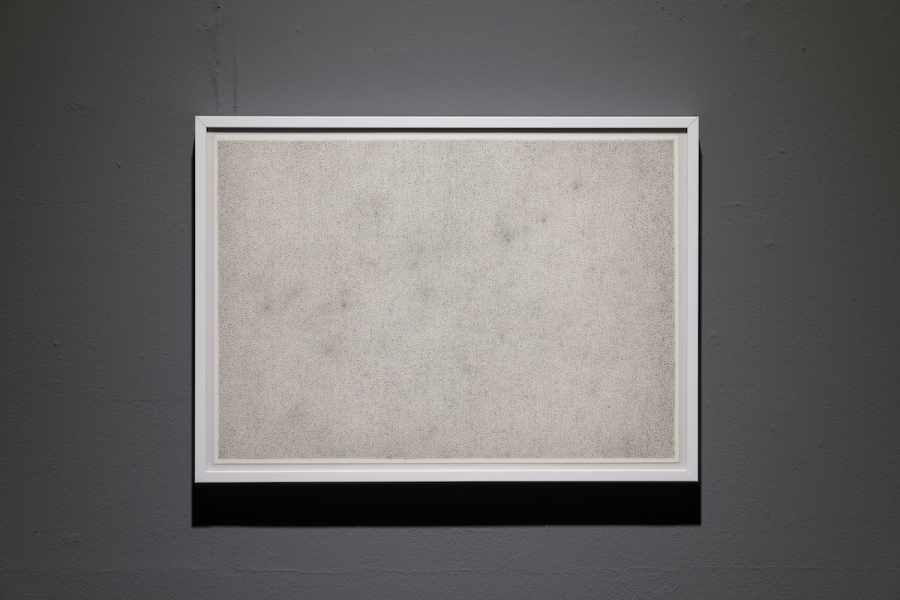

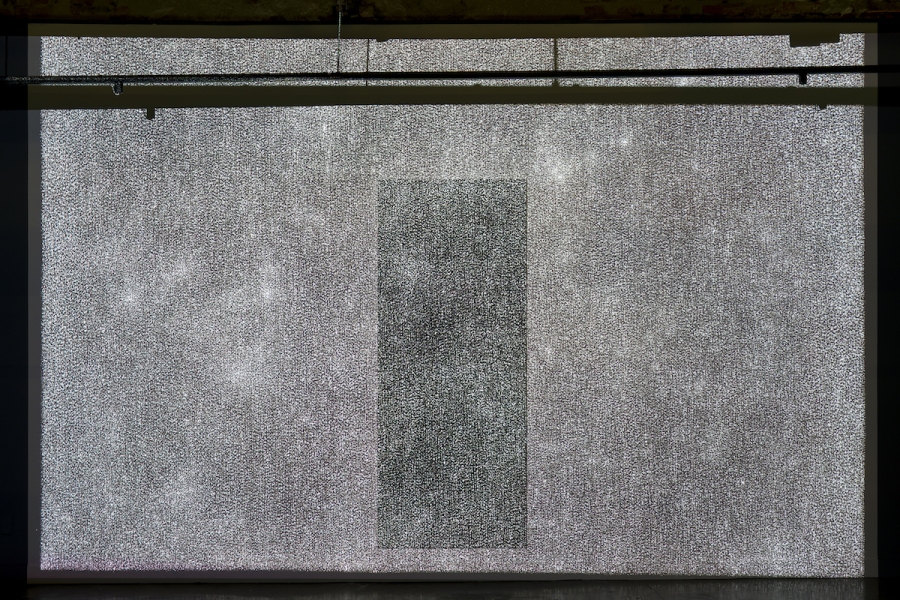

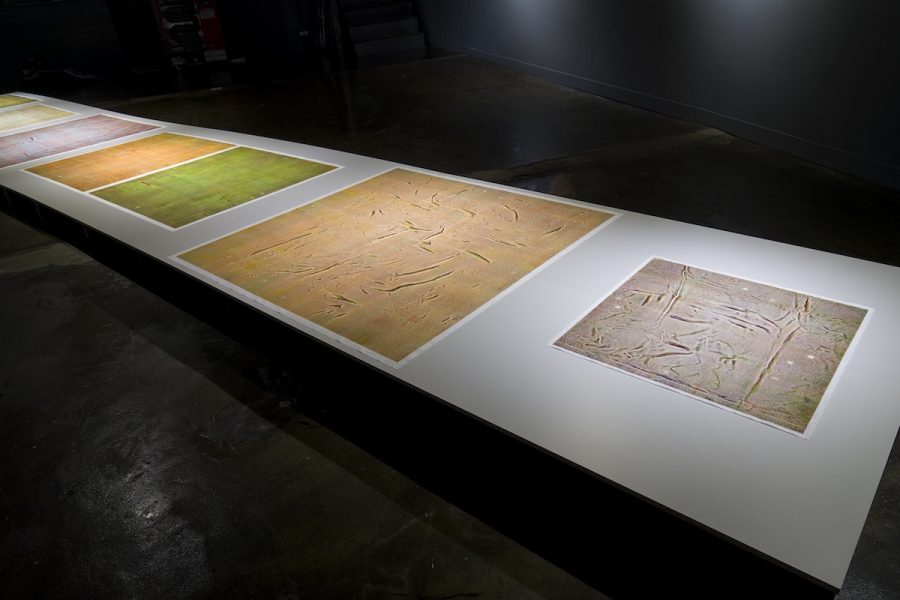

박정우가 2018년부터 실험해온 디오라마 연작 중 최근 작업들을 자세히 들여다보면, 손톱만 한 작은 네모 하나 혹은 여러 개가 화면 어딘가에 항상 자리하고 있다는 것을 발견하게 된다. 그 네모는 나머지 부분보다 희미하고 얕아서 무언가가 결여된 것처럼 느껴진다. 명백히 의도되어 드러나게 된 이것을 없는 듯 취급하고 그림을 감상하기에는 그 존재감이 너무 크다. 자꾸 신경을 쓰게 되는데, 신경을 쓰다 보면 네모가 하나의 기능을 발휘하고 있다는 것을 깨닫게 된다. 그 기능이란 그림이 하나의 통합된 단일 이미지로 함몰되는 것을 방해한다는 것이다. 완결된 그림, 최종의 화면이 이미지로 봉합되기를 거부하며, 회화가 그림의 생성 절차를 열거하는 엄격한 수식 쓰기의 방법으로서 다루어졌음을 알린다. 이를 이해하고 나면 우리는 한 화면이 수없이 반복된 붓질로 이루어졌다는 것을 다시금 인지하게 된다. 그 작은 네모는 보는 이가 이미지로 빨려 들어가기 직전에 뒷걸음질하도록 만들고 그것의 물질적 생성 과정 전체를 추측하게 한다. 그림이 무언가를 연상시키는 재현의 과정에서 우리를 이탈시키고, 그림이 간직한 물질의 기억으로 우리를 이끌고 갔다고 말해도 좋을 것이다. 푸른 음영의 요철, 종이가 울었다 가라앉은 그 흔적으로 인해 젖은 연작이 아름다운 모노크롬으로만 보이지 않게 되는 이유도 엇비슷하다.

이미지이면서 수식이기도 하고, 이미지만은 아니면서도 수식만은 아닌 것이 박정우의 회화라면, 우리는 그의 그림이 이미지와 수식 사이에서 진동하는 불확정적인 무언가라고 말할 수 있다. 이것은 회화이길 놓지 않지만 회화를 넘어서는 새로운 기능을 좇는 것일까? 아니면, 우리가 회화라는 이름을 부름으로써 잊은 회화의 기능을 회복하려는 것일까?

박정우는 회화를 총체적으로 다룬다. 이를 위해 그는 회화를 이루는 구체적인 요소와 조건을 천천히 살피고 열거하는 드문 일을 계속해 왔다.1 여기서 유념할 것은, 박정우에게 회화의 총체성은 그림을 이루는 물질 요소와 도구, 기법 등 가시성의 범주보다 크다는 것이다.2 가능한 복잡한 조건 속에서 본인을 포함한 당대의 회화 작가들이 캔버스 앞에서 더는 나아갈 길 없어 보이는 추상의 길에 어떻게 육박해야 하는지를 살핀다.3 그는 회화라는 관습을 따져 물음으로써 회화 요소의 목록을 작성한다는 측면에서 역사적으로 회화를 이해하고, 당대 화가들의 작업을 세심히 살피며 회화를 (다시) 가능하게 하는 혹은 회화를 위협하는 동시대적 조건들을 도출한다. 그러므로 박정우가 손에 든 ‘회화’라고 하는 용어집에는 분명 끊임없이 요동치는 끝없는 목록이 있을 것이다.

하지만 그의 작업이 고고학자처럼 회화의 흔적을 추적하는 것으로 가득하지는 않다. 박정우에게 그림을 만드는 작업은 회화의 총체성을 다루는 큰 기획의 일부이며, 역사적으로, 문화적으로 또 어떤 이유에서 간과되거나 침묵된 회화의 실재를 강조하여 드러낸다. 회화를 가능하게 하는 조건이지만 은폐된 것, 회화를 가능하게 하는 조건이지만 망각되어 가는 것을 말이다. 박정우의 그림이 시간을 다루는 일에 집중되어 있다는 측면에서 보자면, 그가 드러내려는 회화의 실재란 어떤 이미지가 등장하기까지 이미지의 생산 조건에 따라 구축되는 조형의 과정 자체라고 이해해볼 수 있다. 그의 그림은 이 과정을 숙고하게 만들고, 그리하여 그림 외부의 무언가를 진술하도록 만든다. 여기서 ‘무언가’란, 작가가 혹은 운이 좋다면 우리 모두가 공유하는 필터링 되지 않은 경험적 실재이다. 따라서 그에게 ‘회화를 한다’는 것은 그러한 실재를 등장시키기 위한 “열려라 참깨!”와 같은 특수한 소환술이다. 뮤리얼 루카이저의 연작시 어둠의 속도에 등장하는 “우주는 원자가 아니라 이야기들로 이루어져 있다”는 유명한 문장4, 그리고 “역사는 미메시스가 아니라 디에게시스다”5라는 폴 벤느의 문장을 함께 놓고 생각해보면 이것은 쓰여야만 생성되는 무언가가, 쓰기 자체가 내용이 되는 무언가가 있다는 것을 알려주는 알레고리가 된다. 쓰기의 소여인 것들, 쓰여야만 등장하는 것들이 있다. 그리고 이 알레고리는 박정우가 회화를 통해 하려는 작업이 무엇인지를 이해해보는 데 도움을 준다. 이 전체적인 작용의 시퀀스가 박정우에게 있어 회화라 할 수 있을 것이다. 무엇보다도 이것은 회화를 기능적인 것으로 이해하는 것에서 시작한다.

시간은 우주와 마찬가지로 쓰기의 소여다. 시간은 자연적이고 절대적인 실재임과 동시에 특정하게 구성되고 구조화되어야만 지각할 수 있다는 측면에서 언제나 정치적이다. 그럼에도 우리가 시간을 공기처럼 받아들일 수 있는 이유는 이러저러하게 시간을 조형하는 장치들이 이미 우리 가까이에 자연스레 자리하고 있기 때문이다. 몸은 이미 가장 효율적인 시간 생산 장치다. 다만 우리의 경험은 장치로 산출된 시간을 시간의 실재라고 쉽게 오해한다. 이것은 장치의 정치적, 경제적 전략이기도 할 텐데, 장치는 그 내적 과정을 은폐해야만 생산물을 신비화하거나 상품화할 수 있기 때문이다. 장치의 존재를 폭로하고, 제거하고, 끊임없이 다른 생산 모델을 상상하며 새로운 이미지와 서사를 탐색하고자 한 것이 현대적인 예술의 숙명적인 게임이 된 것은, 장르 내부의 관습을 철저하게 벗겨내고 그 이름을 지탱하는 고유한 필수 조건을 사유하기 시작하면서부터이다. 이 역사적 사건 속에서 회화는 ‘텅 빈 캔버스’만남겨질 때까지 후퇴한다.6

전후 미국 모더니즘에서 이 사건은 회화와 회화가 아닌 것의 변증법적 전개로 이어졌지만, 박정우는 이 역사적 유산을 수용하면서도 그 담론의 재생산이나 변주에 참여하지는 않는다. 그보다는 텅 빈 캔버스라는 전쟁터에서 추상의 기능적 이점을 건져 내고 그것을 들고 당대의 풍경 속으로 걸어 들어간다. 추상의 기능적 이점이란 실재로부터 멀어질수록 역설적으로 그 이미지는 실재에 더 가까워진다는 것이다.7

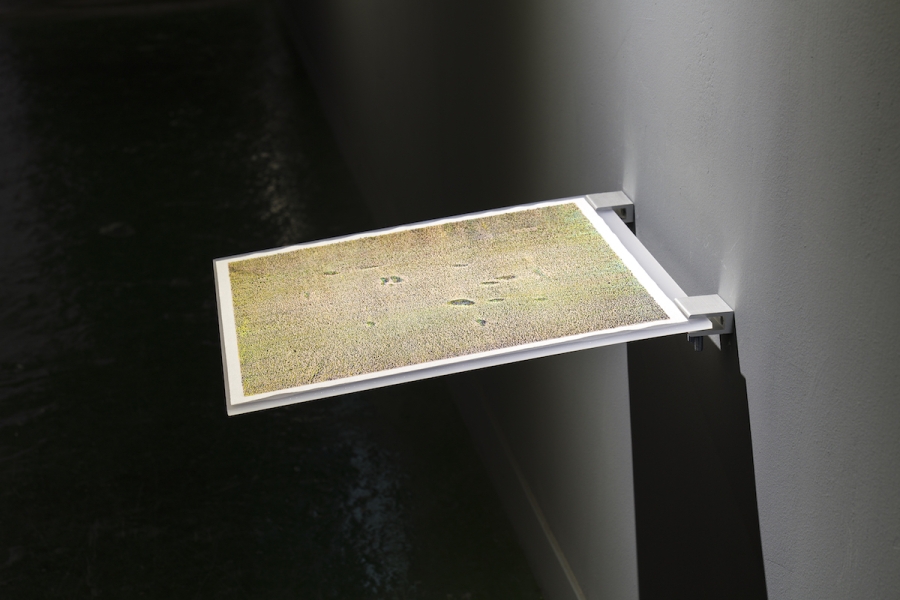

박정우가 자신의 그림에 가장 강하게 개입하는 회화적 몸짓은 붓을 들고 무언가를 그리기 이전에 이미 발생한다. 그림의 밑바탕이 되는 지지체를 선명한 투명함으로 위장하기보다는, 이미 물질인 그것의 숙명일지도 모를 미세한 변형을 인정하고 조형 체계를 구축해 나아가는 조건으로 여기며 거기서부터 그리기를 시작한다는 것이다. 이것은 아마도 그에게 있어서 어떤 이미지가 등장하기 위한 진실을 탐색하는 일일 테다. 그 탐색은 사물이 존재하는 방식에 대한 끊임없는 추측과 증명으로 이루어진다. 우리가 보는 것은 진실을 위해 회화를 도입하는 과정이고, 박정우는 자신의 회화적 생성을 통해 자신을 둘러싼 세계의 조건을 인정하고 천천히 살피는 방식을 보여주는 듯하다. 쌓아 올리는 붓질은 그것의 물질적 조건 위에서 이루어지는 시간의 건축술이며, 우리는 형상 없는 환영을 불러 일으키는 건축적 공간을 거닐게 된다. 이러한 맥락에서 보자면, 그의 작업은 회화를 가로질러 이루어지지만 한편으로는 시간을 형상에서 분리하여 새롭게 공간화 했던 시네마토그라프의 역사와 더 가까워 보이기도 한다.8

박정우가 회화를 총체적으로 다룬다는 말을 곱씹어 보자면, 그는 회화를 통해 다시 세계를 총체적으로 사유한다고도 할 수 있는 것이다. 물론 이는 이미 수많은 예술가의 묘비에 새겨져 있는 야망이고 또한 실패할 수밖에 없는 기획이지만, 성공에 얼마나 가까워졌느냐 보다는 그 불가능성이 도입됨으로써만 드러나는 현실이 값질 뿐이다.

회화를 지성 작용의 산물로, 또 정신적 대상으로 여기고자 한 예술 이론은 오랜 역사를 지녔다. 잃어버린 시간을 찾아서의 2편 꽃핀 소녀들의 그늘에서에는 회화를 ‘코사 멘탈레(cosa mentale)’, 즉 정신적인 것이라고 이른 레오나르도 다 빈치의 말에 대해 다시 생각해볼 수 있는 흥미로운 장면이 나온다. 질베르트가 쓴 편지를 받고 화자인 ‘나’가 기뻐하는 부분이다. 편지를 읽은 화자는 시차를 두고 편지를 편지로서 인식하게 된다. 편지에 담긴 텍스트의 내용이 아닌 편지 그 자체를 향한 인식이 이루어진 순간 그것은 코사 멘탈레의 사물이 된다. 그리고 코사 멘탈레의 사물이 됨으로써 편지를 둘러싼 관계의 미묘한 총체가 등장한다. 그것은 분명 텍스트를 초과하는 것이다.

Looking closely at some of the recent additions to Wu Bak’s Diorama Series, experimentally begun in 2018, one discovers that there are always one or several tiny bite-sized squares somewhere on the picture. The square seems fainter and shallower than other parts of the work, and somehow evokes the sense of a lack. It is too conspicuous, obviously set there with some intention, for the viewer to pretend it does not exist and continue admiring the picture. The square draws attention, and as the viewer gives it attention, one comes to the realization that the square is carrying out a particular function. That function is to hinder the picture from collapsing into one single integrated image. The finished picture, the final canvas refuses to be sutured into one image, and announces that painting has been treated as a rigorous methodology for scripting formulae that lay out the process of a picture’s creation. Understanding this, we come to realize once again that a single picture in fact consists of endlessly repeated layerings of the brush. That small square brings the viewer to step back just before becoming fully immersed in the image, and to ponder the entire physical process of its creation. One could say that the picture trips us up in the process of representing and recalling a thing, and ushers us instead toward the memory of materiality that the picture holds. It is for similar reasons that the uneven bluish shadows of the Wet Series, the traces of paper having warped under moisture and then dried, prevent us from seeing the work simply in a beautiful monochrome.

If Bak’s paintings are images and yet also are formulae, not just an image and yet not just a formula, we could speak of his pictures as an indefinite something that oscillates between the image and the formula. Does this work seek to hold on to being a painting, yet wish to pursue a new function beyond it? Or does it seek to recover a function of painting which we have come to forget as we call it by that name?

Bak works with painting in its totality. To this purpose, he has continually carried out the unusual practice of slowly examining and listing the specific elements and conditions that constitute painting.1 It must be noted here that for Bak, the totality of painting stretches beyond the extent of the visible, including the material elements that make up the painting, tools, and techniques.2 Under these complex conditions of possibility, he explores how artists of his time—including himself—should approach the path of abstraction, at the seeming dead-end of the canvas facing them.3 By questioning the very convention of painting, Bak understands the history of painting through compiling a list of its elements, and by setting a keen eye on the work of contemporary artists, he draws out the contemporary conditions that make painting (again) possible, or those that threaten it. Therefore, the glossary in his hand that bears the name of ‘painting’ will doubtless hold within it an infinite, endlessly undulating list.

Nonetheless, Bak’s work does not solely consist of an archaeologist’s quest after the traces of painting. For Bak, the work of making pictures is part of a larger project that deals with the totality of painting, and emphasizes aspects of the reality of painting that have been overlooked or left unspoken, whether historically, culturally, or otherwise. That is, he reveals that which enables painting but has been concealed; that which enables painting but has been slowly forgotten. Taking into account the fact that Bak’s pictures concentrate on the treatment of temporality, the reality of painting that he seeks to unveil can be understood as the very process of its formation leading up to its emergence, constructed according to the image’s conditions of production. His pictures call upon the viewer to meditate on this process, and thus to testify to something outside the picture. This ‘something’ is an unfiltered experiential reality undergone by the artist, and if we are lucky, shared by us all. Therefore, for Bak, ‘doing painting’ constitutes a special kind of invocation to summon forth this reality, in the vein of “Open sesame!” Juxtaposing Muriel Rukeyser’s famous line from her poetry collection The Speed of Darkness, “The universe is made of stories, / not of atoms,”4 alongside Paul Veyne’s comment that “history … is diegesis and not mimesis,”5 we encounter an allegory that tells us that there is something that arises only by being written, something that takes writing itself as its content—that which is given by writing, that which appears only through being written. This allegory in turn helps us attempt to understand what Bak seeks to do through painting. For Bak, painting comprises the entire sequence of this action. Above all, this work begins by understanding painting as a functional act.

Time, like the cosmos, is given to us through writing. Time is a natural and absolute reality, but at the same time, it is always political in that it can only be perceived through a particular construction and structuring. The reason that we still accept time as naturally as the air we breathe is because various apparatus for the shaping of time already exist discreetly all around us. The body is already the most efficient apparatus for the production of time. It is only that our experience misconstrues the time produced by this apparatus as the reality of time. This can be understood as the political and economic strategy of the apparatus, as the apparatus must conceal its internal process in order to mystify or commodify its product. It is only when art began to thoroughly strip away genre-internal conventions, and to speculate on the necessary conditions particular to the upholding of its name, that the work of exposing the existence of the apparatus, removing it, and endlessly imagining alternate models of production, exploring new images and narratives, became the destined course of the game in today’s art. In the midst of this historical event, painting continues to retreat until all that is left is a ‘blank canvas.’6

In postwar U.S. modernism, this event led to a dialogic development between that which is painting and that which is not. Bak, however, although embracing this historical legacy, does not participate in reproducing or adding variations to that discourse. Rather, he unearths a functional advantage of abstraction from the battlefield that the blank canvas has become, and strolls with it in hand into the landscape of his time. The functional advantage of abstraction is that the further it moves away from reality, paradoxically, its image inches closer to the real.7

The painterly movement that constitutes Bak’s strongest intervention into his pictures takes place even before he lifts a brush to draw something. Rather than camouflaging the foundational object that forms the background for the painting as something distinctly transparent, Bak acknowledges the minute deformities perhaps inevitable to it by virtue of its materiality, and from there begins the work of painting. For Bak, I imagine, this constitutes the work of exploring the truth that enables the emergence of a certain image. Tftehis exploration happens through an endless stream of guesswork and verification about the manner in which objects exist. What we see is Bak’s deployment of painting to the ends of truth, and he seems to show us, through his painterly production, his own ways of acknowledging and slowly scrutinizing the conditions of the world around him. His brushwork, raising up layer after layer, is an architectural craft of time built upon its material conditions, and we are invited to wander through architectural spaces that call forth formless specters. In this context, although Bak’s work deals with painting, it sometimes slips closer to the history of the cinematograph, which dissociates time from the image and newly spatializes it.8

Meditating further on the idea that Bak works with painting in its totality, one could also say that, through painting, he speculates upon the world anew in its totality. This is an ambition etched on the tombstones of countless artists, and a project that is doomed to fail; but rather than its proximity to success, what is truly valuable is the reality that is revealed through the heralding of its impossibility.

There is a long history to theories of art that attempt to take painting as the result of intellectual action, and as a mental object. In the second volume of In Search of Lost Time, “In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower,” one finds an interesting scene that allows us to reconsider Leonardo da Vinci’s maxim that painting is a mental thing, or cosa mentale. It is when the narrating ‘I’ receives Gilberte’s letter and is overjoyed. The narrator, having read the letter, comes to perceive the letter as a letter after a certain interval of time. The moment a perception is made of the letter as itself, not simply in terms of its textual content, the letter becomes an object in the order of cosa mentale. And by becoming such an object, the subtle totality of relations surrounding the letter comes to emerge—and this, undoubtedly, is in excess of the text.

translated by Park Yea Jung

-

여기서 ‘드물다’는 표현이 지시하는 것은 열거의 행위 자체라기보다는 열거를 통해 앎에 이르는 지식 생산 과정 혹은 방법이다. “목록을 작성하는 것만큼 쉬운 일은 없어 보이겠지만, 사실 보기보다 훨씬 복잡하다. 항상 무언가를 빼먹게 되고, 기타 등등이라고 써버릴까 싶기도 하지만, 기타 등등을 붙이지 않아야 정확한 목록이다. 현대의 글쓰기는 (…) 몇몇 드문 경우를 제외한다면 열거하는 기술을 잊어버렸다.” 조르주 페렉, 생각하기/분류하기, 문학동네, 2015, 22쪽. 이번 전시 제목인 “수 금 지 화 목 토 천 해”라는 열거법이 우주의 질서를 파악하는 기억술로서, 그러한 기능으로서의 회화의 알레고리로서 사용된 것은 박정우가 열거를 일종의 앎의 방법으로 인지하고 있음을 알게 해준다. 의미심장한 것은 단어들 사이에 놓인 띄어쓰기인데, 이는 기억술의 한계와 임의성에 대한 인정일 것이다. 즉, 명시적인 것들 사이에 반드시 빈 공간이 있어야만 ‘정확한 목록’이 됨을, 그것이 실재이자 회화적 진실의 구조임을 암시한다.

Here, what is connoted by the expression ‘unusual’ is not the act of listing itself, but rather the process or methodology of reaching knowledge through listing. “Nothing seems simpler than making a list, but in fact it’s much more complicated than it seems: you always leave something out, you’re tempted to write ‘etc.,’ but the whole point of an inventory is not to write ‘etc.’ Contemporary writers (with few exceptions) … have forgotten the art of enumeration” (Georges Perec, Thoughts of Sorts, trans. David Bellos [Boston: David R. Godine, 1985/2009], p. 14). The planetary mnemonic of My Very Educated Mother Just Showed Us Nine, from which this exhibition takes its title, functions as a craft of memory that allows us to grasp the order of the cosmos, and as an allegory of painting in that function; this suggests that Bak conceives of the list as a certain method of knowing. What is meaningful is the spacing between the words, what I see to be an acknowledgement of the limits and arbitrariness of the craft of memory. That is, it suggests that an ‘exact list’ can only be formed by inserting empty space between explicit things, and that this is both reality and the structure of the truth of painting. ↩ ↩ -

회화 요소의 범주와 목록은 곧 박정우가 동시대 회화와 회화 작가를 이해하고 비평하는 규범이기도 하다. 박정우는 이상훈 작가의 개인전 Two Tables(313 Art Project, 2017)를 기획하며 이상훈에 대해 “회화를 구성하는 요소들을 각각의 독립된 ‘차원’으로 고찰하고 이를 토대로 ‘그리기의 체계’를 연구하는 작가”로 설명한다. 그리고 다음과 같이 부연한다. “여기서 회화를 구성하는 요소들이란, 빛과 그림자 같은 광학적인 요소나, 색상이나 윤곽과 같은 조형적인 요소들, 혹은 서포트를 구성하는 프레임과 캔버스 천 같은 구조적 요소들까지도 포괄한다.” 박정우, Two Tables 전시 서문 중에서. 한편 박정우는 회화의 요소에 공간적 조건을 반드시 포함시킨다. 여기서 공간의 개념은 단순히 영역 자체를 의미하는 것이 아니라 특정한 시대의 구체적 조건으로 이해하는 편이 옳다. 즉 회화란 필연적으로 특정한 시대적 조건의 간섭을 통해 생성되는 복잡한 사물이다. “6-70년대 미술인들이, 작업공간에서의 흔적을 통해 과정을 인식할 때만 성립될 수 있는 작품의 실재성을 간과했었다면, 동시대의 미술인들은 회화가 물질적 구조를 지닌 정념의 산물이라는 진실조차 지나친다.” 박정우, 전시 서문, As Small As It Works 전시 도록, 2018, 8-9쪽.

The categories and lists of elements of painting are also the standards by which Bak understands and critiques the contemporary painting and painters of his time. During preparations for artist Sanghoon Lee’s solo exhibition Two Tables (303 Art Project, 2017), Bak described Lee as “an artist who contemplates the elements constituting painting as each an independent ‘dimension,’ and who explores the ‘system of painting’ on the basis of that understanding” He adds: “What I mean by the elements constituting painting include optical elements such as light and shadow, formal elements such as color and shape, and also structural elements such as the frames and canvas fabric used as support” (“Introduction,” exhibition brochure for Two Tables). At the same time, Bak always takes care to include spatial conditions as part and parcel of the elements of painting. Here, the concept of space does not apply simply to a given area, but should rather be understood as the specific conditions pertaining to a particular period. That is, the painting is a complex object that is necessarily produced through the intervention of the conditions of a particular historical period. “If the artists of the ’60s and ’70s lost sight of the reality of the work that can only be established through perceiving the process of its making through the traces left in the working space, artists of our time ignore even the truth that painting is a product of the passions that bears a material structure” (Bak, “Introduction,” exhibition brochure for As Small as It Works, 2018, pp. 8-9). ↩ ↩ -

“그러나 적어도 현대 회화의 비평적 가능성을 모색하는 추상화가들에게, 회화의 질적 규준 혹은 회화 담론의 중력이 사라진 오늘날의 텅 빈 캔버스란, 마치 보르헤스의 소설처럼, ‘가장 완벽한 미로로서의 사막’같은 것일지도 모른다. 그렇다면 갈림길도, 방향의 지표도 없는 이 드넓은 미로의 한복판 위에 선 젊은 추상화가들은 어떻게 출구를 향해 나아갈 것인가?” 박정우, 서문, 성시경 개인전: exit exit 전시 도록, 2019, 2쪽. “그러나 다른 한편으로는, 우리가 발을 내딛고자 하는 물리적 대상이 어떠한 상태인가를 재고해야 하는 상황임을 고려할 때, 돌다리는 가짜 표면으로 뒤덮여 있어서 두드려 보기라도 하지 않으면 대상의 실제 물성을 파악하기 힘든 오늘날의 시지각 환경에 대한 알레고리가 된다. (…) 아무튼 우리는, 돌다리를 건너야 한다.” 박정우, 돌다리: 고근호, 박정우 2인전 전시 도록, 2019.

“But at least for abstract artists seeking out the critical potential of contemporary painting, the blank canvas of today’s world, in which qualitative criteria or gravity of discourses around painting has disappeared, may be something of a ‘desert as the perfect labyrinth’ in Borgesian terms. If so, standing in the middle of this maze-like expanse with no forking paths and no markers of direction, how is the young abstract artist to find one’s way toward the exit?” (Bak, “Introduction,” exhibition brochure for Sikyung Sung Solo Exhibition: exit exit, 2019, p. 2). “On the other hand, considering that we are in a situation to rethink the state of the material object toward which we step, the stone bridge becomes an allegory for the visual-perceptive environment of today’s world, which is covered in fake surfaces so that it is difficult to grasp the actual materiality of the object without at least tapping on it… . At any rate, cross the stone bridge we must” (Bak, exhibition brochure for Before You Leap: Geunho Ko & Wu Bak Duo Exhibition, 2019). ↩ ↩ -

“시간이 들어선다 / 말하라. 말하라 / 우주는 이야기들로 이루어져 있으니 / 원자가 아니라.”, 뮤리얼 루카이저, 어둠의 속도 중에서. 뮤리얼 루카이저 지음, 박선아 옮김, 어둠의 속도, 봄날의책, 2020, 233쪽.

“Time comes into it. / Say it. Say it. / The universe is made of stories, / not of atoms.” From Muriel Rukeyser, “The Speed of Darkness,” in The Speed of Darkness (New York: Random House, 1968). ↩ ↩ -

폴 벤느 지음, 이상길, 김현경 옮김, 역사를 어떻게 쓰는가, 새물결, 2004, 22쪽.

Paul Veyne, Writing History: Essay on Epistemology, trans. Mina Moore-Rinvolucri (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1984), p. 5. ↩ ↩ -

“빈 캔버스마저 이제는 그림으로 간주될 수 있기 때문에 첫눈에 비예술로 보인다는 것이 이제 더 이상 회화에 있어 유용한 판단이 아니라면 예술과 예술이 아닌 것의 경계는 이제 삼차원적인 것에서 찾아져야만 한다. 이 삼차원에 조각이 있었고, 예술이 아닌 모든 물질들도 있었다.” 클레멘트 그린버그, 최근의 조각 중에서. 다음 책에서 재인용; 티에리 드 뒤브 지음, 정헌이 옮김, 현대미술 다시 보기: 모노크롬과 텅 빈 캔버스, 시각과 언어, 1995, 83쪽.

“Given that the initial look of non-art was no longer available to painting, since even an unpainted canvas now stated itself as a picture, the borderline between art and non-art had to be sought in the three-dimensional, where sculpture was, and where everything material that was not art, also was.” From Clement Greenberg, “Recentness of Sculpture,” in Minimal Art, A Critical Anthology, ed. Gregory Battcock (New York: Dutton, 1968), p. 182; qtd. in Thierry de Duve, Kant after Duchamp (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), pp. 225-26. ↩ ↩ -

마레의 크로노포토그라피가 이에 대한 의미 있는 참고가 될 수 있을 것이다. 마레는 움직임을 포착하고 분석하기 위한 과학적 방법으로서 사진을 도입했는데, 엄정한 과학적 이미지를 얻기 위해 재현적 형상을 지우고 단순한 그래픽적 형태만을 축출한 연속 사진을 발명했다. 박상우 지음, 박상우의 포톨로지: 베르티옹에서 마레까지 19세기 과학사진사, 문학동네, 2019, 237-271쪽.

The chronophotography of Marey can be a meaningful reference here. Marey deployed photography as a scientific method for capturing and analyzing movement, and to the ends of getting a rigorously scientific image, he invented the serial photograph, which erases the representational figure and extracts only the graphic form. See Park Sangwoo, Photology: A History of 19th-century Scientific Photography from Bertillon to Marey (Munhak Dongne, 2019), pp. 237-271. ↩ ↩ -

“두 종류의 영화가 있다. 연극의 수단들(배우, 연출 등)을 사용하며, 복제의 목적으로 카메라를 사용하는 영화[시네마]가 그 하나다. 시네마토그라프의 수단들을 사용하며, 창조의 목적으로 카메라를 사용하는 영화 [시네마토그라프]가 다른 하나다.” 로베르 브레송 지음, 이윤영 옮김, 시네마토그라프에 대한 노트, 문학과지성사, 2021, 15쪽.

“Two types of film: those that employ the resources of the theater (actors, direction, etc.) and use the camera in order to reproduce [cinema]; those that employ the resources of cinematography and use the camera to create [cinematograph].” From Robert Bresson, Notes on Cinematography, trans. Jonathan Griffin (New York: Urizen Books, 1977), p. 2. ↩ ↩