눈을 감는 일

나의 정원은 생태학적으로 건강하다. 비록 정원에서의 모든 작업이 이미 있던 지대를 파괴하기는 하지만 말이다.

- 데릭 저먼, 정원 중에서

우리가 그 속성을 전혀 모르는 무엇이야말로 종종 우리가 발견해야만 하는 것이고, 그것을 찾는 일은 길을 잃는 일이나 마찬가지다.

- 레베카 솔닛, 길잃기 안내서 중에서

모든 것과 아무것도

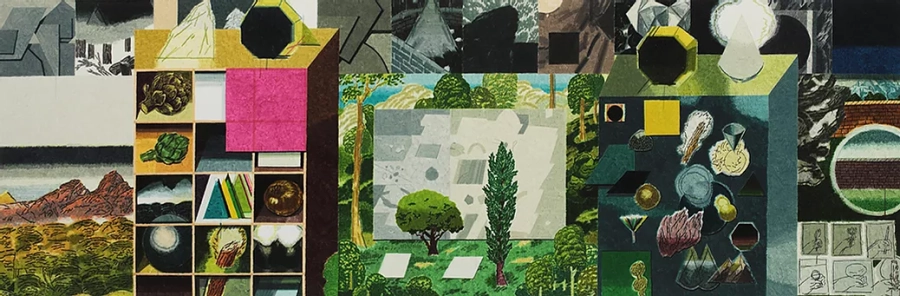

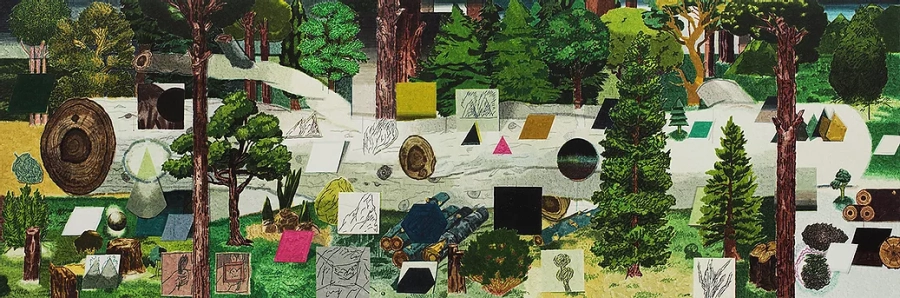

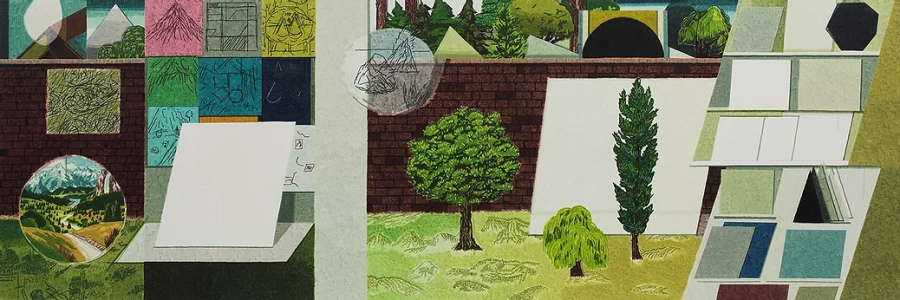

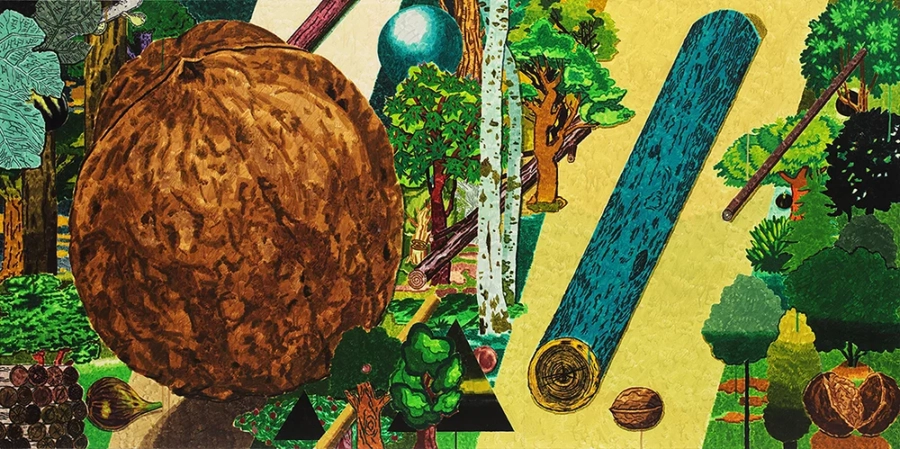

모든 것과 아무것도. 전현선의 회화로 곧장 들어가게 해 주는 이보다 더 나은 표현은 없을지도 모르겠다. 위켄드(Weekend)에서 열린 개인전 모든 것과 아무것도(2017)에는 가로로 긴 세 개의 캔버스가 하나씩 각각의 벽을 차지하고 서로 일정한 간격을 두어 걸렸다. 숲이 생겨나며 빽빽해진 평면 위로 이런저런 기하학적 형태들과 메모-그림이 자신의 자리를 찾아내 수다한 풍경을 이루고(쓰러진 흰 나무와 숲), 하나의 점에서 두 개의 서로 다른 세계가 갈라져 자라난 이유를 추측하며 사물의 시간을 더듬어 나열하고(원래는 하나의 점이었던 두 개의 세계), 벽이라는 분리의 장치보다는 사물 사이의 거리와 닮음을 중심에 둠으로써 공간을 통합한다(안과 밖, 가깝고(도) 먼). 분명한 것들이 가득하지만 무엇도 분명하다고 말하기 힘들다. 모든 것이자 아무것도 아닌 것의 등장은 가시적인 사물들이 서로의 간격을 관계의 이유로 가지고 있을 뿐 무엇도 확정하지 못한다는 사실을 인지하게 되는 순간이다. 이는 작가의 표현에 따르면 “굳건하게 서 있는 나무들로 가득 찬 숲”처럼 보이지만 사실은 “끊임없이 무너져 내리는 늪”1인 실재로, 반복되는 (형태의, 의미의, 관계의, 이야기의) 발생과 소멸의 운동을 일으킨다.

형식과 어둠

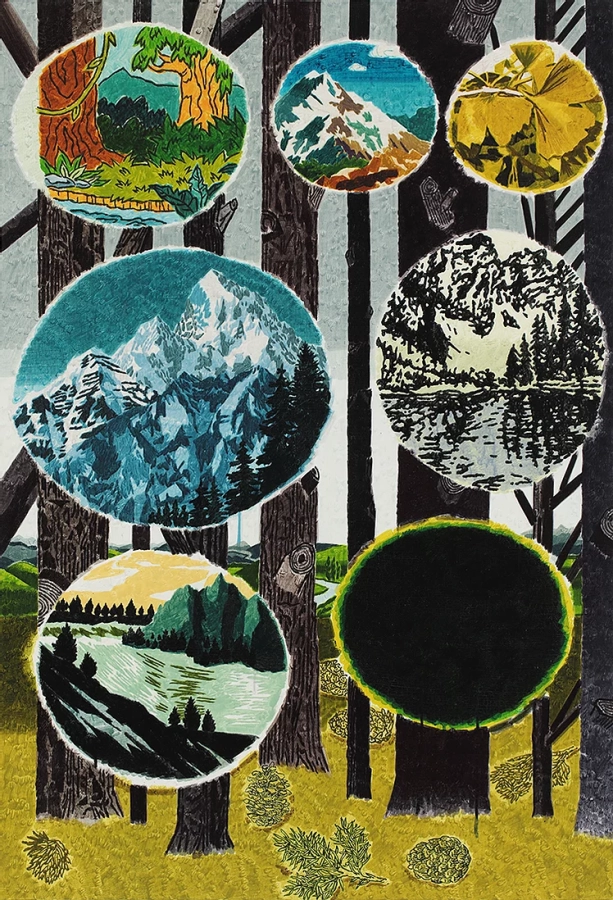

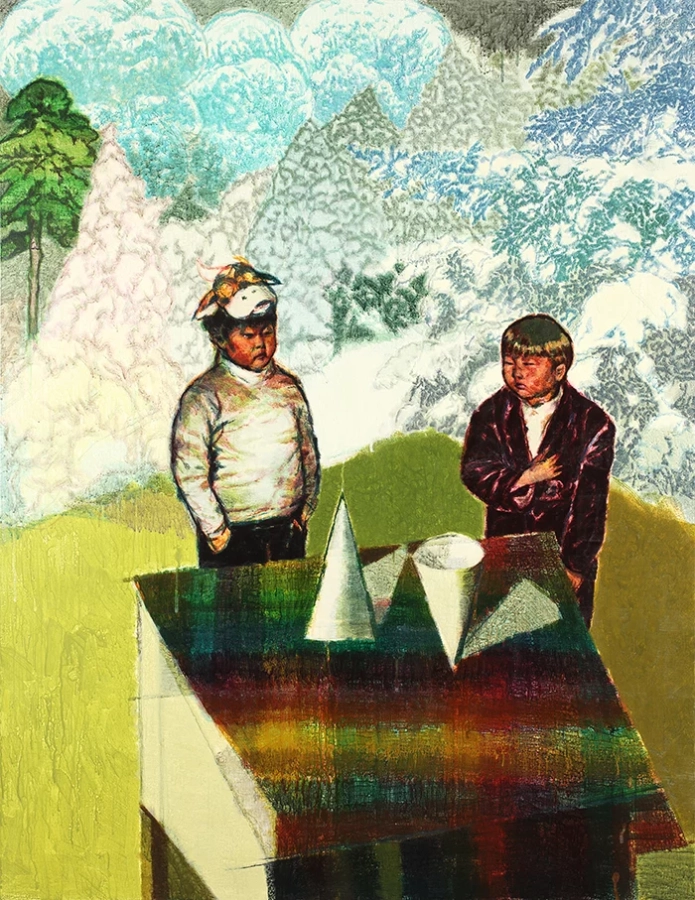

눈에 보이는 것은 오직 형식이다. 전현선의 회화에서 가장 빈번하게 그리고 중요하게 등장하는 형식은 원뿔이다. 원뿔은 말 그대로 원뿔이기도 하고, 동물의 뿔이기도 하고, 산이기도 하고, 바위이기도 하고, 열매이기도 하고, 관계의 구조이기도 하다. 이 형식은 세계의 어떤 것들, 구체적으로는 작가가 의문을 품고 매혹되는 사물을 이해하는 방식이자 무언가가 드러나는 방식이다. 그리고 형태의 닮음에만 국한되지 않고 그것이 머금은 시간 또한 다루는 것이기도 하다. 하지만 전현선의 원뿔은 어딘지 이상하다. 그것 자체는 비어 있고 그것을 둘러싼 사물의 관계만이 펼쳐진다. 자기 자신은 값을 가지지 않는 매개변수다. 작가의 회화 세계 전체가 일종의 연극이라면, 원뿔은 매번의 역할을 수행하는, 순간마다 자신의 몸짓을 욕망하는 즉흥 연기자다. 그렇게 의문에 부쳐진 형식은 오직 특정한 관계의 순차 안에서만, 즉 이야기로서만 등장하는 것이다. 전현선은 원뿔을 이르러 “파악되지 못하고 판단이 유예된 대상들”이라 한다. 그리고 이를 마법사 오즈에 비유하는데, 왜냐하면 그 추상적 존재는 형상이 구체적으로 정해져 있지 않고 그것을 마주하는 주체에 따라 그때그때 새로운 형상으로 드러나기 때문이다.2 이런 맥락에서 전현선의 많은 그림이 숲을 간직하고 있는 것은 우연이 아닐지도 모른다. 오래 전부터 신비로운 이야기들의 배경이 되어 긴장과 공포와 낭만을 선물했던 숲은 인간으로서는 파악할 수 없는 수많은 사물들의 유동적 관계의 총체이다. 거기서 길을 잃을 때, 비로소 숲은 자신의 내밀한 갈림길을 내어 준다.

전현선의 회화에 대해 생각하는 일은 폭이 크고 속도가 느린 너울을 따라간다. 너울의 가장 높은 곳에서는 선명한 형식들이 드러나고, 가장 무거운 아래쪽에는 무엇도 보이지 않고 아무것도 들리지 않는 소란스러운 어둠이 있다. 생각을 놓아 버리지 않는 한 흐름은 보여주기와 철회하기를 번갈아가며 이어진다. 원뿔이 그러했던 것처럼, 종종 눈에 보이는 무엇도 고정되어 있지 않고 확실하지 않다는 사실로 인해 불안하기도 하지만 이 불안은 이내 막연한 기대로 뒤바뀌곤 한다. 내가 알아차리지 못하고, 내가 이해하지 못하고, 또 나와는 크게 관계되지 않더라도 분명 어떤 형태와 흐름이 만들어지고 있다는 기분 때문이다. 생성에의 지각은 불안과 기대라는 양가적 정동을 불러일으키는 모순된 순간이면서도 사물들의 새로운 관계와 세계의 구체적인 다른 구성에 대한 가능의 순간을 전망하게 한다는 점에서는 낙관적이다.

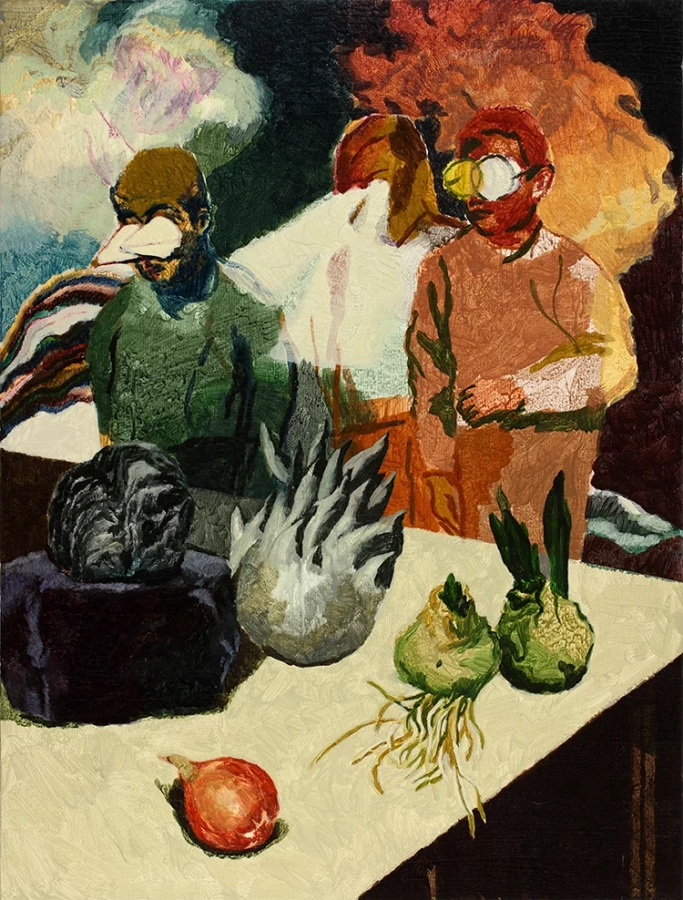

이 경험의 요체는 나의 판단을 옴짝달싹 못 하게 구속하는 힘과 당황스러울 정도로 한없이 느슨하고 듬성듬성하게 만드는 힘의 반복적인 작용이다. 이것은 눈을 감았다 뜨는 일과 어딘지 비슷하다. 보기와 침묵하기가 반복되고 그 모든 주기의 마디마다 세계가 깜빡이며 (다시) 등장한다. 눈을 오래 감을수록 세계는 분명 이전보다 더 새삼스럽다. 그리고 어둠이 깊어질수록 이미지와 사물의 뒷면에 보다 가까이 다가간다. 그런데 이 너울을 따라가다 보면, 문득 이것은 작품이 촉발하는 구성적인 힘으로서 내게 전달된 것이기도 하지만 한편으로는 작가 또한 따를 수밖에 없었던 삶의 한 원리가 아니었을까 추측하게 된다. 가시적인 형식들을 의문에 부치고 의문을 형식에 맞세우기 위해 스스로를 지진대 위에 올려둔 모습을 상상한다. 전현선에게는 이 지진대 위에서의 시간이 그림을 그리는 일로 드러난다. 서툰 관찰자들(2015) 속 세 인물은 각자 원뿔, 흰색 광선, 두 알의 색이 다른 안경 등을 눈에 얹고 저마다의 보기를 하고 있지만 무엇도 보지 못하는 것 같이 경직된 자세를 취한다. 그들의 앞에는 양파라거나 불꽃이 옮겨붙은 구체가 있지만 누구도 이를 제대로 인지하지 못한다. 인지되지 못한 사물은 보기 앞에서도 여전히 무엇으로도 확정되지 않는다. 서툰 관찰자의 기록(2015)처럼 그저 테이블 위로, 정원 속으로, 벽 안으로 – 그리고 캔버스 위로 – 자리를 이동해 (다시) 등장하게 될 뿐이다. 서로 다른 시간과 공간에 흩어져 있던 것들이 그 맥락에서 떼어 내어져 한 자리에서 모인다. 보기를 반복하고 의문을 지속하며 형태들의 자리를 찾아 나가는 것이다. 파고가 잠잠해지고 나면 지난 흐름의 총체는 비로소 회화로 다다른다. 아니 어쩌면 그리기와 회화가 오랜 시간에 걸쳐 거친 요동을 세심히 다독여 형태로, 구성으로 잠재운 것일지도 모르겠다. 서툰 관찰자의 회화는 여러 시차적 간격을 품었다 꺼내어 놓음으로써 세계에 다가선다.

너울을 맞이하는 것은 신비로운 사건으로 기억된다. 반복됨으로써 양태로 드러나는 것, 세계와 삶 속에서 가시화되는 것 즉 형식을 통해 우리를 깊은 어둠으로 끌고 내려가기란 쉽지 않은 일이기 때문이다. 게다가 어둠이 다시 가시적인 세계의 새로운 구성으로 우리를 안내하기는 더더욱 쉽지 않다. 그 드문 리듬은 형식으로 형식의 이유를 해체하는 일종의 자기모순을 통해서만 가능한 파괴적인 힘을 가진다. 명료한 형식과 구조로 구성됨에도 불구하고 등장하는, 조르조 데 키리코가 그려내는 초월적 세계처럼 말이다. 이 너울의 신비는, 그것에 몸을 맡겨 시간을 흘려보내다 보면 어느 순간 높은 곳과 낮은 곳, 즉 형식과 어둠의 자리가 뒤바뀌는 순간을 맞이하게 된다는 것에 있다. 어둠이 실재가 됐을 때 형식은 소여로 남을 것이다. 그것은 형식을 가능하게 하는 현상적 경험의 축적과 그로 인해 산출된 규칙이, 즉 응당 세계가 그러하다는 믿음이 다시는 이전으로 돌아갈 수 없는 운명을 마주하게 되는 것과도 같다.

때문에 전현선의 회화는 세계에 대한 하나의 인지 모델이라고도 할 수 있다. 그의 회화적 실재는 저 너머의 (초월적) 세계가 내포한 여러 가능성 중 하나가 발생적으로 전개된 풍경도 아니고, 사물들의 관계와 서로 간의 영향을 도식화하는 지도도 아니다. 그보다는 작가에게 있어 삶의 진실이라고 여길 수 있는 바로 그 너울의 아득한 간극 사이에서의 끊임없는 움직임, 즉 그것의 양끝은 지각할 수도 말할 수도 없다는 인지 불가능성이다. 그의 회화는 바로 그 불가능성의 문제를 검토해 나가는 일이며 불가능성을 이유로 세계를 대칭성의 공간으로 그려 낸다. 어두운 낮(2018)의 검고 엄격한 8각형의 면이 그것이 관여하는 정사각 프레임 안의 자명한 사물들, 풍경과 팽팽하게 긴장을 유지하는 것처럼 말이다. 가시성의 반대편에는 언제나 알 수 없는 무언가가 존재한다는 믿음은 이분법적이지만, 그의 회화는 이와 같은 플라톤적 사유를 아래위로 뒤집는다. 너머의 세계에 대해 상상하고 그것의 흔적을 좇는 것이 아니라 모든 불안정이 생성되고 반복되는 곳이 바로 너머의 세계를 정향하게 만드는 실재라고 말이다. 그러므로 전현선의 회화의 목적은 어둠을 사유하는 것도, 세계 곳곳에 편재하는 형식을 찾아내는 것도 아니다. 그저 멈추지 않는 진동, 그 힘의 작용만을 따라가며 삶의 형식을 발견함과 동시에 재배치하고 그것에 관여한 힘의 체제로 문제를 돌려놓으며 실재의 신비를 재생산한다. 여기서 재배치의 주체로서 전현선은 권위나 권한을 가지고 무언가를 조직하는 이, 관리자를 뜻하는 것은 아니다, 그보다는 최대한 사물의 편에서 이유 없는 그들의 존재 방식을 좇는 이에 가깝다. 파동은 사실 무한한 회전 운동의 반복에 의해 발생한다는 점은 의미심장하다.

둘의 신비

너울이라는 움직임이 전현선의 인지 방법과 회화의 구조, 그리고 그에 대한 경험을 총체적으로 다루기 위한 추상적 도식이라 했을 때, 이 힘에 선행하는 근원적인 원리는 ‘둘의 신비’다. 형식과 어둠은 둘의 신비 자체이기도 하면서 둘의 신비가 환기시키는 인식론적 문제들 중 하나다. 전현선은 끊임없이 둘의 신비를 다룬다. 세계의 수많은 존재 방식 중 둘의 문제를 가장 주의 깊게 관찰한다. 그것은 단순히 하나와 다른 하나의 총합이라기보다는 어떤 가능성들, 되돌리고 회복될 수 없이 분산되고 분열되는 삶의 무한한 사건을 불러오는 일이다. 이것이 내가 다른 어떤 용어가 아니라 ‘신비’라고 부르는 이유다. 긴장 없이는 신비가 있을 수 없으며, 긴장은 둘로 인해 생겨난다. 여기서 말하는 긴장이란 심리적 용어가 아니라 수 없이 많은 관계의 양태가 자세를 취하기 직전, 역학이 힘을 발휘하기 직전, 어떤 암시만이 가득한 기묘한 순간을 이른다. 작가는 두 개가 한 짝이어야 할 구두가 하나만 남았을 때의 불안에 대해 묘사하며, 둘의 신비에 대해 이렇게 쓴 적이 있다.

“0과 1, 그리고 1과 2는 서로 똑같은 간격을 유지하는 숫자들이다. 하지만 0과 1사이에서 느껴지는 간격보다 1과 2 사이의 간격이 더 크게 느껴진다. 하나에서 둘이 되는 것은 기적처럼 느껴지기도 한다. 둘이 되면 할 수 있는 일이 많아지기 때문이다. 서로를 거울처럼 바라볼 수도 있고, 맞부딪혀 소리를 낼 수도 있다. 서로에게 어울리는 이름을 붙여줄 수도 있다. 하지만 이렇게 할 수 있는 일이 많아지는 대신, 2가 다시 1과 1이 되면 더 이상 그 전의 1과 1이 아니게 된다. 무작정 산 편도 티켓으로 먼 곳을 갔다가 다시는 돌아올 수 없게 된 상황처럼 1이 2가 되는 것은 돌아올 수 없는 강을 건너는 것과 마찬가지이다. 이처럼 일반적으로 두 개가 짝을 이루어야 하는 것이 하나만 보인다면 불안한 분위기가 풍길 것이다.”3

하나의 부재 또한 둘이 취하는 관계의 양태 중 하나다. 그리고 아마 둘이 취할 수 있는 관계의 양태는 헤아릴 수 없이 많을 것이다. 우리는 그중 아주 적은 수만을 규칙화할 수 있다. 하얀 원뿔들(2017)에서 두 개의 산처럼 크고 텅 빈 원뿔은 그 끝이 서로 조금만 겹쳐 놓여 있고, 나란한 길(2018)의 거대한 호두와 통나무는 각자가 바라보는 방향에 따라 각자의 길을 가진다. 2020년에 진행한 숫자 시리즈 작업은 배경과 형상 간의 배치를 찾는 반면 눈앞의 풍경(2017)은 배경 위에 또 다른 풍경을 심어 둔다. 이러한 대립과 대비의 구도는 사물이 이상한 존재로서 존재할 수 있는 가능성을 추측하며 의미가 지연되기를 요구한다.

전현선의 회화에서 의미의 경기장만큼 내게 흥미로운 것은 작가가 자신의 회화 속에서 둘의 문제를 첨예하게 다루기 위한 조건을 구축한다는 점에 있다. 뿔과 대화들(2014), 비슷하고 다른 말투(2014) 등 의미의 임의성과 주관성, 대화의 불가능성을 암시하는 작품들에는 어김없이 두 인물을 사이에 두고 (평면도형으로 보일 정도로 입체감 없는) 테이블이 놓여 있다. 두 인물은 테이블의 주위에서 약속되지 않은 몸짓과 표정을 주고받는다. 탁자 위의 오해(2015)에서는 심지어 탁구대가 놓여 있지만 게임이 이루어질 기미는 보이지 않고 인물들은 저마다의 경기에 열중한다. 협의와 게임을 위한 테이블에는 전혀 통약되지 않을 사물들이 나란하다. 비슷한 맥락에서 그림의 순간(2016)에는 두 형태에 동등한 자리를 부여하기 위해 크고 높은 좌대가 들어차 있다. 이 작품의 제목이 정직하게 말하고 있는 것처럼, 여기서 둘의 신비는 캔버스의 속성과 한계 안에서 등장한다는 점에서 언제나 회화적이다. 회화임을 은폐하는 환영이 아니라 회화이기 때문임을 강조한다. 이에 대한 보다 내밀한 해석은, 전현선에게 있어 둘의 신비는 그저 두 사물이 함께 있다는 것만으로는 발생하지 않음을 이해한다는 것일 테다. 비어있는 종이(2017)나 메모지 위의 산(2017), 산 그림(2017) 등은 직접적으로 회화 자체와 그보다는 작은 회화적 공간을 구분한다. 사물들의 관계를 위한 공간을 할당하면서, 동시에 회화 자체 또한 사물로 규정함으로써 회화가 스스로 ‘둘’ 중 하나가 됨을 잊지 않도록 하는 것이다. 그렇게 예술 작품 또한 (안전지대를 벗어나) 삶의 진실을 구성하는 둘 중 하나가 될 수 있도록 한다. 개인전 검은 녹색 잎(2018)에서부터 선보이기 시작한, 사물 없이 순수한 기하학적 도형들 간의 관계로만 화면이 구성된 그림들에서는 이러한 회화의 사물적 측면이 강조되어 있다. 이 순수한 평면 도형들을 위한 회화적 공간이란 오직 캔버스의 빈 공간 자체이기만 하면 충분하다. 하지만 이는 삶의 진실을 곱씹기에는 너무나도 손쉬운 봉합처럼 보이기도 한다. 건조한 긴장은 둘의 신비를 약화시키고 텅 빈 침묵 속에서 형태와 물질만을 더욱 강조한다.

캔버스 프레임 안의 평면은 그가 주시하는 둘의 문제를 첨예하게 다룰 수 있는 일종의 놀이터이다. 형태의 배치에서 시작할 수도 있고, 형태를 위한 자리를 마련하는 것에서 시작할 수도 있다. 무엇이 되었든 사물에 귀기울인다면, 거기서는 사건이 발생한다. 전현선의 회화가 세계를 재현하는 것과는 무관한 이유다. 재현은 발생보다는 발견의 행위와 더 관련되어 있다. 만약 사물이 구체적인 세계에 놓여 있다면 둘의 문제는 결코 둘의 문제만으로 남겨질 수 없을 것이다. 물질은 세계의 모든 힘의 작용으로부터 자유롭지 못하기 때문에 어떤 현상이 오로지 둘의 문제에서 비롯된 것이라고 단정하기는 대단히 어려워진다. 무엇보다도 물질은 너무 명백하게 즉각적으로 ‘그것’이어서 뻔뻔하게 자기를 부정하고 다른 무엇이 된 척 태연할 수 없는 노릇이다. 그리하여 전현선에게 둘의 신비는 세계에 다가서기 위한 방법이면서도 회화의 대상으로 협상되는 것이다. 아니 오히려 둘의 신비를 다루기 위해 그에게 회화 자체가 요청되었는지도 모르겠다. 둘의 신비는 세계를 인지하는 인식론적 방법이자 사물이 드러나는 존재론적 방법이며, 회화는 이 둘 사이를 연동시키는 무한한 한계다. 때문에 현대적인 예술로서는 드물게도 예술 작품으로서의 자기 지시성 안에서 영혼의 문제, 삶의 진실성의 문제를 생각하게 만든다. 여기서 드물다고 말한 것에는 거의 대부분의 현대적 예술은 오직 예술 작품으로서의 자기 지시성만을 가질 뿐 그 안은 텅 비어있곤 하기 때문이다. 이 특별한 이중의 진술은 작가와 관객이 동일한 삶의 영토 속에서 서로를 확인할 수 있게 해 준다.

분명한 것은 그림을 그리는 이로서, 사물의 존재론을 삶의 진실과 연동시키는 사람으로서 세계를 형식과 어둠 사이의 진동으로 인식하는 일은 캔버스 평면 위에서 형태가 발생하고 관계가 구축된 이후에 일어난다는 점이다. 전현선에게 둘로 구조화된 세계란 균형을 위한 체조(2014)에서 원뿔들의 다양한 형태와 인물의 자세가 서로 간 균형을 맞추려는 시도처럼 사물과 이름의, 이미지와 이야기의 균형을 찾아가는 과정이지 윤리를 뒷받침하는 예시나 유토피아에 대한 상상이 아니다. 그의 회화는 이분법적 사고 사이를 가로지르는 사물 세계의 수다스러움을 경청한다.

진실의 작은 조각들

온갖 사물과 도형들이 화면 안에서 자신의 존재를 뽐내며 열성적으로 대화하는 활력의 그림은 사실 그 자체로 매혹적이다. 하지만 메모들(2016)을 보았을 때, 나는 꽤나 의아했고 조금은 당황스러웠던 것 같다. 그것은 다른 방식으로 나의 말하기를 가로막았는데, 격자 위에 올라간 작은 네모 안의 드로잉은 부서져 있고 결핍되어 있어서 말을 하는 것 자체를 멋쩍게 만들었기 때문이다. 혹은 기대나 공포, 불안과 설렘처럼 또렷한 감정이 아니라 규정하기에는 너무 작고 사소해서 자신의 자리를 가지지 못한 어떤 기분을 느꼈기 때문이었는지도 모르겠다. 나는 그 그림이 무얼까 이해하기 위해서는 오랫동안 생각할 수밖에 없었다.

전현선은 마치 포스트잇 메모를 붙이듯 화면 위에 작은 네모들을 올려 두는 작업을 2016년부터 지속해 오고 있다. 사물과 기록과 뿔(2016)을 참고하자면, 이와 같은 메모들은 일종의 ‘기록’임을 알 수 있다. 사물과 기록과 뿔은 메모들처럼 캔버스의 뒷면으로 여겨지는 격자 위에 메모-그림과 여러 도형, 사물들이 마치 경이의 방(Wunderkammer)을 연상시키듯 빽빽하게 들어차 있다. 아감벤은 이 온갖 사물이 들어찬 경이의 방에 대해 “혼돈이 지배하는 듯 보이지만 혼돈은 하나의 섣부른 인상”에 지나지 않으며, 그것은 “복잡한 조화로움 속에서 동물과 식물, 광물의 세계를 재생해내는(재생해 내는) 일종의 소우주”였다고 그 세계관을 설명한다. 그리고 의미심장하게도 “사물들 하나하나는 같이 모여 있을 때에만 의미를 지닐 수 있었다”며 그 조화의 원리를 말한다.4 기록, 그리고 그것을 회화에서 드러내는 메모-그림은 전현선의 그림에서 사물과 뿔과 같은 위상으로 다루어지며, 그것들과 함께 관계에 참여한다. 여기서 다시 한 번 사물과 사물의 관계에 대한 전현선의 입장을 곱씹어 본다. 그의 기록은, 그가 사물을 의문에 부친 것처럼, 자명한 어떤 기억이 아니라 이해할 수 없지만 존재감을 지닌 어떤 순간에 관한 것일 테다. 그리고 그것 또한 사물과 마찬가지로 판단이 유예된 대상으로서, 회화 안에서 사물들 간의 관계를 통해 삶의 진실을, 회화적 실재를 재생산한다. 둘의 신비의 관점에서 보자면 이것은 형태나 사물과 대비되는 해상도 낮은 이미지다. 나란히 걷는 낮과 밤(2017)에는 이와 같은 온갖 크고 작고 선명하고 불투명한 기억들이 사물과 풍경과 원뿔들과 함께 가득 들어차 있다. 활력 있는 것과 희미한 것, 의미심장한 것과 사소한 것이 같은 리듬을 공유한다.

메모-그림은 그것이 메모라는 점에서 언제나 파편적이고 단편적이며 어떤 순간을 잡아 두는 이미지일 것이다. 메모지 위에 쓰는 글은 돌이켜 보면 엉터리일 때가 많다. 의식과 의도의 심도가 얕은 그 순간의 단상은 꾹꾹 눌러 쓴 구문론적으로 완전한 문장보다는 단어들의 부서진 조합을 요구하곤 하기 때문이다. 하지만 나는 그것이 엉터리이기보다는 어떤 대상을 서술하기 위한 필연성이자 고유한 방법이라고 생각하는 편이다. 롤랑 바르트 또한 메모의 행위를 글쓰기와 구분되는 것으로 여기며, “현재의 파편을 의식 속에 솟아오르는 대로 포착할 필요성”에 의한 도구라고 말한다. 그리고 그것은 “나에게 감각적인(아주 사소한) 소식들, 그리고 살면서 직접 ‘전부 알고자’ 하는 소식들을 전해준다.”5 메모는 분산 속에서, 그러니까 사물과 현상을 예의 주시하지 않고 그것 없는 텅 빈 공간을 힐끗 보는 것과의 연관성 속에서 가능하다. 때문에 메모는 훗날 돌이켜 보면 해석되지 않고 이해되지 않을 때가 많고, 어떠한 노스탤지어도 흥미도 불러일으키지 못하는 먼지 같은 기억일 수 있다. 하지만 누군가는 그 먼지가 진실의 파편이라고 믿기도 한다.

프랑스의 역사학자 아를레트 파르주는 “진실의 작은 조각들이 지금 이렇게 아카이브에 좌초해 있다”고 여기며 아카이브를 기반으로 전개되는 역사 연구가 진실에 다다르는 독특함에 대해서 설명한다.6 파르주에 따르면 “아카이브는 담론에 가려져 있던 것들을 엿볼 수 있는 곳, 규범적인 행동이나 정형화된 행동이 파기되면서 다양한 행동들, 의외의 행동들, 그야말로 틀을 벗어나는 행동들이 출현하는 곳”이고 이러한 아카이브 속 자료는 “이미 만들어져 있는 이미지들을 깨뜨린다.” 그는 아카이브의 “날것의 기록”이 어떻게 일상의 안쪽을 엿보게 해 주는지, “아카이브 취향”의 작업자가 어떻게 “베일을 찢는 감각, 앎의 불투명함을 헤치고 나아가는 감각, 불확실했던 긴 여행을 거쳐 드디어 존재들과 사물들의 본질에 가닿는 감각”과 함께 진실을 찾아가는지 알려 준다. 흥미로운 것은 아카이브가 진실이라기보다는 모순과 거짓과 소동이 뒤섞인 “실재”이기에 강력하다는 파르주의 주장인데, 왜냐하면 아카이브 자료가 ‘거짓의 진술’이라고 하더라도 아카이브의 작업자가 진실로서 성찰하는 것은 바로 그와 같은 진술을 가능하게 한 총체적인 관계의 양태와 힘의 역학이기 때문이다. 실재란 그런 어수선함으로 가득 차 있고 의미는 실재에서 산출된다. 파르주에게 있어 역사학자의 소명이란 크고 작은 “충돌을 성찰의 동력으로 삼는 것, 나아가 충돌이 동력이 되는 역사를 써내는 것”이므로 이 충돌의 실재를 역사화하기 위해서는 “감정적 차원을 계산할 줄 알아야 하고 비언어적 차원을 언어화할 줄 알아야” 할 필요가 있는 것이다.

말하자면 아카이브 취향의 작업자가 진실을 구하는 장소는 파편 그 자체가 아니라 널부러진 파편들 사이에 봉합되지 않고 남아 있는 어떤 시간과 공간이다. 이렇게 세계를 이해하고 산출하는 이들에게 있어 진실이란 간격을 매개로 서로 관련 없이 동떨어져 있는 것들, 그 간격이 아니면 의미 없고 무용하며 확정되지 않을 것들, 자리를 가지지 못하고 분류되지 못하고 이름을 가질 수 없었던 것들, 감정을 가졌으나 표현되지 못한 것들을 동시에 조직함으로써 추측되는 것이다. 그것들의 떨리는 목소리를 듣고 멈칫하는 움직임을 의미 있게 관찰하면서 말이다. 여기에는 통합과 동일시, 단일화에 대한 의심이 선행한다. 이미지와 서사 안에 모순과 불화가 있어야만 함을 믿는다.

메모-그림은 순서 없는 이유들(2018)처럼 만화에서 볼 수 있는 분할 화면 그림의 형식으로도 변주된다. 각각의 분할 화면은 다른 화면들과 동시적으로 관계를 맺지만 그 분할 사이의 순서와 간격은 가늠할 수 없다. 여전히 신비는 그곳에서 생겨난다. 메모의 주요한 특성은 그것이 조직화되고 해석되는 데에는 어느 정도의 시차와 배치의 임의성이 필요하다는 것에 있다. 낱장의 메모는 게시판에서 혹은 노트 위에서 (혹은 캔버스) 위에서 임의의 자리에 붙고 또 이리저리 자리를 옮겨 붙으며 끊임없는 몽타주의 변주를 수행한다. 파편은 진실에 관한 또 다른 형식으로서 방향 없는 연결이라는 행위를 요청하는 것이다. 전현선이 회화를 통해 지켜 내려는 것은 바로 이와 같은 간격이다. 둘의 신비의 본질적인 조건이란 아마 이것일 테다. 시간과 공간의 어긋남에서 사물의 진실이 등장한다. 이는 이질적인 시간과 공간이 하나의 화면 위에 덩어리처럼 뒤엉켜 있는 모습과 동전의 양면 같은 것이어서 구분하기 어렵지만, 하지만 엄밀히 구분되어야 할 입장이다. 진실에 다다르는 방식에 관한 쟁점이기 때문이다.

집과 숲

“집이 있고 바깥세상(숲)이 있다. 그 둘은 경계로 나뉘어 있다. 집을 나서서 새로운 경험을 하고, 또 하나의 경험담을 만들어 다시 집으로 돌아온다. 이 여정이 나의 작업에 있어서 중요한 장치이자 줄거리이다…(중략) 집을 안정과 균형이라 정의할 때, 이야기는 안정감이 깨지면서 시작되고 다시 균형을 회복하는 과정을 따라 전개된다고 할 수 있다.”7

더 많은 사물들이 등장하고 상상할 수 없는 이야기를 가지기 위해서는 더욱 깊고 어두운 숲속을 향해 길을 잃어 나가야 한다. 그러나 길을 잃는 일은 단언컨대 정말로 무서운 일이다. 그럼에도 불구하고 그것을 감수해야만 하는 데에는 저마다의 이유가 있을 것이다. 저마다의 방식으로 숲에 다다르고 다시 집을 지어 올린다. 그 집은 종종, 아니 늘 비어있을 것이다. 하지만 집은 또 다른 누군가가 숲속에서 길을 잃고 자신을 발견한 뒤 문을 열고 들어올 것을 알고 있기에 오랫동안 말 없이 기다린다.

My garden is ecologically sound, though work of any kind disrupts the existing terrain.

- Derek Jarman, The Garden

That thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you is usually what you need to find, and finding it is a matter of getting lost.

- Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost

Everything and Nothing

Everything and nothing. There may be no better expression than this when diving into Hyunsun Jeon’s paintings. In the solo exhibition Forests and Swamps (2017) at Weekend, three canvases with long horizontal edges occupy each wall at regular distances. On the plane a thick forest emerges; various geometric shapes and memo-pictures find their place and form a dense landscape (Everything and Nothing-Fallen White Tree and Forest, 2017). The assemblage of the passage of time asks why a single point would split into two worlds (Everything and Nothing-Two Worlds that Were Once One, 2017). The integration of space centers on the distance and resemblance between the objects, rather than on the division of the wall (Everything and Nothing-Inside and Outside, Near and Far, 2017). Many things are clear, but also nothing is that clear. The moment when everything becomes nothing is when visible objects maintain their space merely for relational reasons and nothing else. According to the artist, the reality is “a forest full of strong upright trees” but also “a swamp that is constantly falling apart.”1 This causes a repetitive cycle of birth and decay (of its forms, meanings, relations, and stories).

Form and Darkness

The only visible thing is form. The most frequent and important form in Hyunsun Jeon’s paintings is the cone. A cone is literally a cone, or an animal’s horn, or a mountain, or a rock, or a fruit, or structures of relationships. This form is a way of understanding the objects that draw the artist’s fascination and curiosity; it is also a way in which something reveals itself. It is not limited to morphology but is also about its time. Jeon’s cone, however, is somewhat peculiar. It itself is empty, and what we see is the relationship of objects that surround it. It is a parameter without a value. If we can read the artist’s oeuvre as a kind of a play, a cone is an improv performer who executes every role while always desiring their own movements. Such an undetermined form appears only within a certain sequence of relations, that is, only as a narrative. Jeon refers to cones as “undetermined objects for which judgment is suspended.” She further likens the cone to the Wizard of Oz, because as an amorphous abstract being, it changes its appearance depending on the subject it encounters.2 In this context, it may not be a coincidence that many of Jeon’s paintings have forests in them. The forest has long been the site of myth and a source of tension, fear, and romance; it is the sum of all the fluid relations of numerous objects that are undeterminable to humans. Only by getting lost in a forest can we have a glimpse of its intimate crossroads.

To contemplate Jeon’s painting is to keep astride a wide, slow wave. At its peak clear forms arise; at its trough lies darkness that is invisible; inaudible, yet loud. Unless I let go of my thoughts, the flow keeps revealing and concealing. As with cones, there is a sense of anxiety that arises from the indeterminacy of what I see, but it quickly turns into vague anticipation. I feel that certain forms and flows are being created even though I cannot notice, understand, or even relate to them. The perception of creation is contradictory in that it evokes the ambivalent effects of anxiety and expectation, and optimistic in that it allows us to anticipate a moment when a new relationship between objects and another concrete composition of the world emerges.

The gist of this experience is the repetition of power that both restrains my judgment and makes it endlessly lethargic and sparse. It is somewhat akin to the blinking of an eye. Sight and silence repeat themselves, and the world flickers and (re)appears at every cycle. The longer I close my eyes, the more new the world feels. The deeper the darkness gets, the closer we get to the rear end of an image and object. Following this wave, I am led to speculate that while this effect is triggered by the work itself, it also is a principle of life that the artist had to follow. I imagine myself in a seismic zone, in order to call all the visible forms into question and to pose the questions against the form. To the artist, the act of painting reveals the time spent in this seismic zone. The three protagonists in Curious Observers (2015) wear a cone, a white light beam, and glasses with two different colored lenses, and each does the looking while taking a rigid posture as if they can’t see anything. In front of them are onions or spheres on fire, but no one really recognizes them. The unrecognized objects remain unidentifiable. As in Curious Observer (2015), they merely relocate and (re)appear on the table, in the garden, inside a wall—and on the canvas. Scattered across time and space, objects are now removed from their contexts and reunited in one place. It is a process of repeatedly seeing, questioning, and finding where their forms belong. When the tides quiet, the flow finally reaches the painting. Perhaps drawing and painting managed to tame the turbulence with their forms and compositions. The painting of a curious observer approaches the world by embracing and introducing several parallax-like gaps.

Encountering the wave was a mysterious event. The mystery lies in the difficulty of form—that is, the repetitive pattern or visualization—to draw us into the trench of indeterminacy. What is even more difficult is getting out of that trench to a world of visibility. This sporadic rhythm wields its destructive power only through acts of self-contradiction of breaking down the reason for its own form. This is similar to a transcendental world depicted by Giorgio de Chirico that emerges despite clear forms and structures. The mystery of this wave comes from letting ourselves ride along, and arriving at a moment in which the highs and lows, the form and trench of darkness, are inverted. Only when the darkness is actualized will the form become a priori. This is when the accumulation of phenomenological experiences and the resulting rules — that is, the belief that the world is as such—face their irreversible fate.

Jeon’s painting can, therefore, be understood as a cognitive model. Her pictorial reality is neither an exposition of a landscape that depicts the many possibilities intrinsic to the (transcendental) world, nor is it a map schematically illustrating the relationship between objects and their influences on each other. Rather, it is a continuous fluctuation between the waves that can be regarded as the Truth for the artist. In other words, it is the (cognitive) impossibility or unutterability of both ends of the wave. Her painting is precisely the exploration of this impossibility and the portrayal of the world as a space of symmetry built on this impossibility. It is as how the pitch-black, impeccable octagonal plane in Dark Daytime (2018) maintains tension with the self-evident objects and landscape within the square frame. If the belief that there is always something unknown on the other side of visibility is dichotomous, Jeon’s paintings reverse this Platonic belief. Instead of imagining the world beyond and following its traces, they assert that the site of instability and its repetition is the reality that orients the world beyond. The purpose of her painting, therefore, is not to think about darkness as such or to find a form that pervades the world. Rather, it is to discover the forms of life by tracing the workings of ceaseless oscillations, to rearrange those forms, and to reproduce the mystery of reality by re-appropriating those forms to the structure of the forces involved in the process. Here, Jeon, as the subject of this rearrangement, does not act as an authoritative organizer or a manager; rather, she is closer to one who follows the groundless existence of these objects from their side as much as possible. After all, waves are created by the repetition of infinitely rotational motions.

The Mystery of the Two

Assuming that the wave’s movement is an abstract schema that expresses Jeon’s cognitive method, the structure of her painting, and the holistic treatment of that experience, the fundamental principle preceding this force is the “mystery of the two.” Form and darkness are, themselves, the mysteries of the two, while they are also one of the epistemological problems that their mysteries evoke. Jeon constantly explores the mystery of the two. Of the many modes of existence in the world, the problem of the two is observed most carefully. It is not simply the sum of one and the other, but rather the summoning of certain possibilities resting in the infinite events that are irreversibly dispersed and divided. This aspect is why I call it “mystery,” and not any other term. No mystery exists without tension; tensions arise from the two. Tension here is not a psychological term but the peculiar moment right before countless forms of relationships take up a pose, just before the forces are put into action, when only hints are potent in the air. The artist describes the anxiety when shoes don’t make a pair and writes about the mystery of the two as in the following:

“Zero and one, and one and two are numbers that are equally spaced from each other. But the gap between one and two feels greater than that between zero and one. Becoming two from one almost feels like a miracle, because when you become two, there are many things you can do. You can look at each other like in a mirror, or you can run into each other and make sounds. You can even give each other names. While a lot of things are possible, when two become separate ones, they are no longer what they used to be. Similar to not being able to come back from a far-away place after having recklessly bought a one-way ticket, one becoming two is like crossing a river that cannot be uncrossed. As such, if there is only one thing that generally exists in pairs, there will be a sense of uneasiness.”3

The absence of one is also one way of existing as two. Perhaps, there may be countless relational forms that the two can take. We can schematize only a few of those forms. In White Cones (2017), the large, empty mountain-like cones overlap only slightly at their ends, and the huge walnut and the logs in Parallel Paths (2018) each have their own courses depending on the direction they are facing. The Number series done in 2020 explores the arrangement between the background and the objects while Inside Outside (2017) places another landscape on top of the background. This confronting and contrasting composition speculates on the possibility that objects can exist as odd beings; it further demands a delay of their meanings.

What is as interesting as the arena of signification in Jeon’s painting is that the artist establishes the acute conditions for the problems of the two in her paintings. In works that suggest contingency, subjectivity, and the impossibility of dialogue such as Horn and Conversations (2014) and Similar and Different Way of Speaking (2014), there is always a table (that is almost two-dimensional) between the two protagonists. Around this table, these two exchange uncoordinated gestures and expressions. In Misconception on the Table (2015), there is even a ping-pong table, but there is no sign of the game taking place while the protagonists are absorbed in their own games. At the table made for discussions and games only lies a line of incommensurable objects. In a similar vein, Moment of a Painting (2016) fits a tall and large pedestal that gives equal status to both forms. As suggested by the candid title, the mysteries of the two here are always pictorial in that they are bounded by the limits of the canvas. There is no attempt to conceal its painterly nature. Instead it is emphasized. A more intricate interpretation of this composition would come from Jeon’s understanding that the mystery of the two does not arise by simply being together. An Empty Paper (2017), Mountain on a Paper (2017), and Mountain Painting (2017) more directly distinguish the painting itself from the smaller pictorial spaces. While allocating spaces for the relationships between objects, the painting itself is also construed as an object so that it not be forgotten that the painting itself becomes one of the “two.” This conceptualization allows for the artwork to also become (by coming out of the safe zone) one of the two that constitute the Truth. This was initially shown in her solo exhibition Black Green Leaves (2018): the paintings that are composed solely of the relationship between pure geometric figures without objects to emphasize the materialist aspects of painting. The empty space of the canvas itself is all the pictorial space that these flat figures need. But it also seems this closure is one that too easily mulls over the truth of life. Dry tension erodes the mystery of the two and emphasizes only the form and matter in empty silence.

The plane within the canvas frame is a playground that allows a rigorous examination of the problem of the two. It can start with the arrangement of the shapes or with the securing of the space for those arrangements. Whatever the object happens to be, an event emerges from a careful scrutiny of the objects. This is why Jeon’s paintings have nothing to do with representing the world. Representation has more to do with the act of discovery than with the occurrence. If objects are placed in a material world, the problem of the two can never remain only as such. Since an object is never free from the effects of different forces in the world; it becomes very difficult to conclude that a phenomenon originates solely from the problem of the two. Above all, an object is so obviously and immediately “that thing” that it is impossible to deny its materiality and pretend it is something else. For Jeon, the mystery of the two is as much a way to approach the world as it is a way to negotiate the object as the subject of a painting. Rather, it may be more accurate to say that the painting itself was employed to address the mystery of the two. The mystery of the two is an epistemological method of recognizing the world and an ontological method in which objects are revealed. Thus the painting is an infinite limit that co-activates the two. For this reason, Jeon’s work makes us think about the problems of the soul and the truth of life within the bounds of self-referentiality, as contemporary art hardly does. What I mean by “hardly done” is that almost all contemporary art assumes self-referentiality without substance. This special double testimony allows the artist and the audience to identify each other in the same terrain of life.

What is clear is that as a painter and as one who links the ontology of objects with the truth of life, recognizing the world as an oscillation between form and darkness takes place after forms emerge and relationships are established on the picture plane. For Jeon, structuring the world in two is a process of finding the balance between objects, names, images, and narratives; just as the various cones and postures of the figures in Gestures for Balance (2014) attempt to find their balance. It is not an imaginary utopia or an example that supports any ethical claims. Her paintings heed the clamorous world of objects that cuts across dichotomous thinking.

Fragments of Truth

The vivacious painting in which all kinds of objects and figures flaunt their existence and enthusiastically interact with each other is in itself fascinating. When I saw Notes (2016), however, I was quite surprised and a bit puzzled. It stifled me in some ways, as the drawing nesting in the small square of the grid was broken and incomplete, rendering speech itself futile. Perhaps it was because the work didn’t evoke clear emotions like anticipation, fear, anxiety, and excitement but only those that are too trivial to define and occupy space. I had to dwell on the painting for a while to understand what it was.

Since 2016, Jeon has been working on putting small squares on the screen like sticking on post-it notes. In reference to Objects, Drawings and the Cone (2016), one can see that such memos are a kind of “record.” Similar to Notes, the painting Objects, Drawings and the Cone is packed with memo-pictures, figures, and objects on a grid that appears to be the back of a canvas. Such a composition is reminiscent of a Wunderkammer, or a cabinet of curiosities. Giorgio Agamben describes this cabinet of curiosities as where “chaos seems to reign, but [where] chaos is nothing more than a premature impression,” or “a sort of microcosm that reproduced, in its harmonious confusion, the animal, vegetable, and mineral macrocosm.” He further underscores the principle of harmony: “the individual objects seem to find their meaning only side by side with others.”4 Records, and memo-pictures as their container, are given a status equal to that of the objects and horns in Jeon’s paintings. It is also the records and memo-pictures that form relationships with the objects. Here, once again, I contemplate Jeon’s position on the relationship between objects. Similar to how she questions the objects themselves, her records might not be about some self-explanatory memories but about a moment that is inscrutable yet present. As with objects, that moment delays judgement and reproduces the truth of life and pictorial reality through the very relationships among the objects. From the point of view of the mystery of the two, this moment is a low resolution image, unlike a form or object. In Parallel Paths-Day and Night (2017), large, small, lucid, and opaque memories fill up the canvas with other objects, landscapes, and cones. The vibrant and faint, the meaningful and trivial share the same rhythm.

A memo-picture will always be fragmentary and deficient in that it is precisely a memo, an image that captures a certain moment. Notation is often nonsense. It is often written with shallow depth of consciousness and intention, resulting in a broken combination of words rather than syntactically complete sentences. Still, I tend to think of it as an inevitable and unique method of describing an object rather than being pure nonsense. Roland Barthes also regards the act of notation as distinct from writing; it is a tool born out of “the necessity to capture the present fragments as they rise in the consciousness.” He further writes that notation “delivers (very trivial) sensational news to me, those that I want to know all about in my life.”5 Notation is possible in the dispersion, that is, when not much attention is paid to objects and phenomena while glancing over the empty space in between. For this reason, notations are often difficult to interpret or comprehend in a second look; they even become a part of a dusty memory for which neither nostalgia nor interest arises. Some believe that this very dust is a fragment of truth.

French historian Arlette Farge writes that “little pieces of truth are stranded in the archives” to explain the uniqueness of reaching the truth through historical research based on the archives.6 According to Farge, “archive is a place where you can glimpse those that are hidden in the discourse; unexpected behaviors, those that go beyond the normative framework,” and information within this archives thus “breaks the preexisting images.” She further explains how the archives’ “raw record” gives us a peek into the inside of daily life, how the “archive connoisseur” approaches truth with a “sense of tearing the veil, a sense of getting past the opacity of knowledge, and a long journey of uncertainty” to arrive at “a sense of reaching the essence of beings.” Interesting is Farge’s assertion that archives are powerful precisely because they are not “real” per se, but because they are a mix of falsities and contradictions of reality. Even though the archived material is “false,” the overall relationship and the dynamics that made such a claim possible are what the reader considers to be truth. Reality is full of such clutter, and meaning comes from reality. For Farge, the task of the historian is to “make the conflict a driving force for reflection and to write a history in which conflict is the driving force.” And in order to historicize the reality of this conflict, we need to know “how to see the emotional dimensions and how to verbalize the non-verbal.”

In other words, the site of truth, in the allure of the archives, lies not in the fragments themselves but in a certain space and time that remains within the crevices of the scattered fragments. For those who understand and see the world this way, truth emerges from reconstructing the unrelated, meaningless, indefinite, groundless, unclassifiable, un-nameable, and unexpressed things that only exist in the crevices. It can be reached by listening to their trembling voices and scrutinizing the stutters in between. Preceding this process is the skepticism of integration, parallels, and homogeneity. There must be faith in the contradictions and discords of images and narratives.

In works including Reasons for Nothing (2018), memo-pictures are also transformed into split-screen drawings like in comic strips. Each split screen simultaneously relates to other screens, but the order and interval between these screens are undetermined. Here again, the mystery arises. A memo’s main trait is that it requires some parallax and possibility of arbitrary arrangement in its interpretation and organization. A piece of a memo is randomly placed on a bulletin board or on a notebook (or canvas) and then moved from one place to another, performing endless montage variations. In other words, a fragment is another form of truth that calls for an act of undirected connection. It is this in between space that Jeon is constantly trying to preserve through her paintings. The essence of the mystery of the two lies here. The truth of objects emerges from the discord of time and space. While the line between a hodgepodge of heterogeneous time and space on the canvas and this intricate display of discords is a fine one, the separation should remain clear as it is one that concerns how we reach the truth.

Home and Forest

“There is home, then there is the outside world (forest). The two are divided by a border. Leaving home and experiencing anew, creating another story and returning home, this journey is an important device and plot in my work… Having defined the home as stability and balance, stories begin when that sense of stability is broken and a process of restoring balance unfolds.”7

For more objects to appear and have their unimaginable stories, we have to get lost in a deeper, darker forest. Getting lost is indeed very scary. Nevertheless, we will each have our reasons to bear this fear. We each reach the forest in our own ways and build our homes again. The houses will often, no, always be empty. But the house waits silently and patiently, knowing that someone will get lost in the woods again and open its door.

번역 유소윤

-

전현선, 모든 것과 아무것도의 도록에 수록된 작가 노트 중에서.

Hyunsun Jeon, “artist notes,” in Forests and Swamps (2017), Exhibition catalogue. ↩ ↩ -

전현선, 그림이 된 생각들, 열림원, 2015, 14~15쪽.

Hyunsun Jeon, Thoughts that Became Paintings (Seoul: Yolimwon Publishing Group, 2015), 14-15. ↩ ↩ -

조르조 아감벤, 윤병언 옮김, 내용 없는 인간, 자음과 모음, 2017, 73쪽.

Giorgio Agamben, The Man without Content (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 30. ↩ ↩ -

롤랑 바르트, 변광배 옮김, 롤랑 바르트, 마지막 강의, 민음사, 2015, 167쪽.

Roland Barthes, The Preparation of the Novel: Lecture Courses and Seminars at the Collège de France, 1978-1979 and 1979-1980, trans. Kate Briggs (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011). ↩ ↩ -

아를레트 파르주, 김정아 옮김, 아카이브 취향, 문학과지성사, 2020.

Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives, trans. Thomas Scott-Railton (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015). ↩ ↩ -

전현선, 앞의 책, 39~40쪽.

Jeon, Thoughts that Became Paintings, 39-40. ↩ ↩