둘의 픽션

블라디미르 나보코프의 창백한 불꽃의 머리말 마지막 문단에서 작중 인물인 찰스 킨보트는 이 책을 읽는 방법에 대해 다음과 같이 조언한다.

“‘이러한 상황’에서는 책장을 앞뒤로 넘겨야 하는 번거로움이 있으니 시 본문이 실린 부분을 잘라 묶어두거나, 그보다 간단하게 아예 책을 두 권 사서 편한 테이블 위에 나란히 펴놓고 보는 것이 현명하리라 생각한다.”1

창백한 불꽃이 어떤 내용인지 모르는 독자가 있을 수 있으니, 이 조언이 어떤 맥락에서 나온 것인지 간단히 설명해보겠다. 창백한 불꽃은,

- (찰스 킨보트가 쓴) 머리말,

- (존 셰이드가 쓴) 999행에 이르는 창백한 불꽃: 네 편으로 된 시,

- (찰스 킨보트가 쓴) 시에 대한 130개의 주석,

- (찰스 킨보트가 쓴) 색인

이렇게 네 부분으로 구성된 작품이다. 언뜻 보면 전형적인 시집의 편집 구성을 닮았기에 오해할 만 하지만, 미국의 작고한 시인으로 설정된 존 셰이드와 주석자이자 편집자로 설정된 찰스 킨보트는 모두 가상의 인물이다. 그러므로 창백한 불꽃은 (시가 아닌) 시집의 형식을 소설에 도입한 나보코프의 픽션이다.

창백한 불꽃: 네 편으로 된 시에 대한 주석을 쓰고 책을 편집한 인물인 킨보트는 머리말에서 독자들에게 일반적인 관행대로 시를 먼저 읽고 주석을 보지 말고, 주석을 먼저 보고 시를 읽기를 권유한다. 그리고 시를 읽고 나선 다시 주석을 참조하며 시에 대해 이해하라고 한다. 주석과 시를 이리저리 오가며 글을 읽으라는 말이다.

‘이러한 상황’이란 이를 뜻한다. 코덱스 형태의 책을 이런 방식으로 읽으려면 책을 앞뒤로 뒤적이며 왔다갔다 해야 하는 번거로움이 있으니 아예 두 권의 책을 사서 펼쳐 놓고 같이 보라는 말이다. 이 문장은 읽기를 좀 더 편안히 효율적으로 수행할 수 있는 적절한 방법을 조언하는 것처럼 이해되기도 해서 흘려 들을 수도 있지만,창백한 불꽃의 진정한 픽션은 바로 이 ‘두 권의 책’으로부터 비롯한다. 쓰인 글은 그저 ‘두 권의 책’에 소요되기 위한 것이라고 나는 감히 주장할 수 있다.2

그런데 저자의 진지한 제안에도 불구하고 같은 책을 두 권 구비하여 이 소설을 읽은 사람이 과연 얼마나 될까? 그 수를 정확히 알 수는 없겠지만, 매우 적을 그 사람들에게 이 소설은 분명 한 권의 책만으로 소설을 읽은 독자에게는 내어주지 않은 픽션을 전했으리라 확신한다. 그러면 그 픽션이란 뭘까?

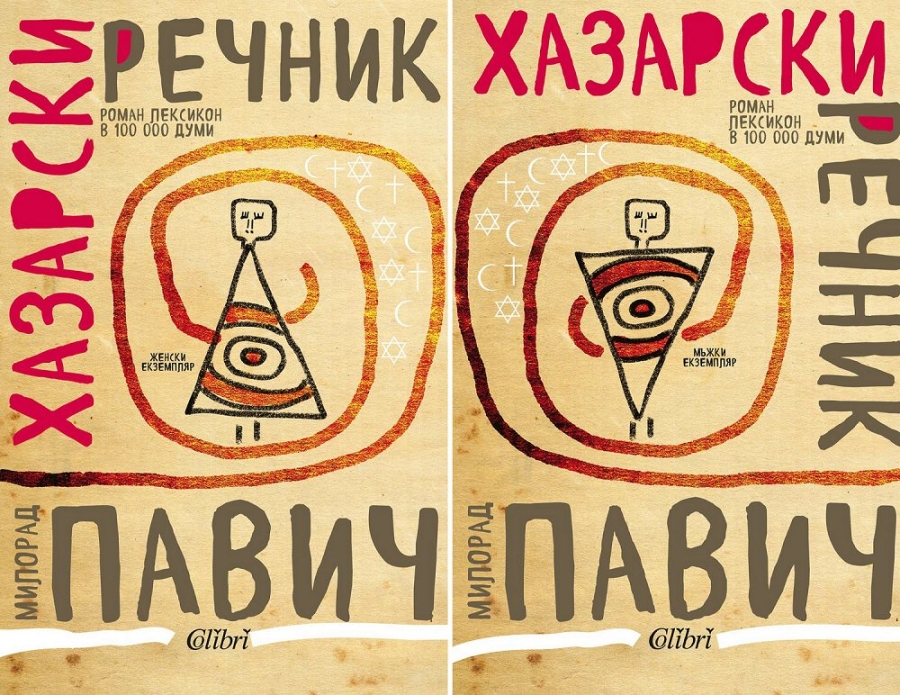

보다 결정적인 ‘두 권의 책’은 여성판, 남성판 두 판본으로 출간된 밀로라드 파비치의 카자르 사전이다. 이 책의 서문 세 번째 절 ‘사전의 사용법’은 이 책에 대하여 창백한 불꽃의 찰스 킨보트와 엇비슷한 읽기를 독자에게 제안한다.

“대다수 독자들은 스스로 적당하다고 생각하는 방식으로 이 책을 이용할 수 있다. 다른 모든 사전이 그렇듯이, 어떤 독자들은 당장 흥미를 끄는 단어나 이름부터 찾아볼 수도 있고 또 어떤 독자들은 한 자리에 앉아서 처음부터 끝까지 하나의 완결된 텍스트를 읽듯이 읽어 내려갈 수도 있다. 그렇게 해서 카자르 민족과 그들의 문제 그리고 그와 관련된 사건들에 대한 완성된 그림을 그려 볼 수 있을 것이다. 이 책은 프로이센 판이 그러했듯이 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 넘길 수도 있고 오른쪽에서 왼쪽으로 넘길 수도 있다. 이 사전에 포함되어 있는 세 가지 책은 어떤 순서에 따라 읽어도 무방하다.”3

위의 인용문을 통해서도 쉽게 눈치챌 수 있듯, 카자르 사전은 사전의 구성을 닮았다. 사전을 처음부터, 순서대로, 끝까지 정독하는 사람은 많지 않을 것이다. 사전은 대개 필요한 부분을 찾아서 읽고 덮거나, 명백한 이유가 없을 땐 여기저기 뒤적거리며 이것저것 눈에 띄는 것을 읽고 다시 책꽂이로 치운다. 사전에는 사전이 가진 단어 수와 같거나 그보다 많은 수의 출입문이 있고, 문들은 온갖 방향으로 연결되어 있다.카자르 사전은 이와 같은 읽기를 통해 ‘무한대에 가까운’ 서사를, 개별 이야기들의 집합을 초과하는 거대한 전체를 기대하고, 여기에 필요한 긴 시간에 책이 관여하기를 바란다. 이것만 해도 카자르 사전의 픽션은 이미 독자의 현실 감각을 초과하는데, 정말로 더 큰 문제는 이 책이 ‘두 권의 책’이라는 점이다.

카자르 사전의 여성판, 남성판 두 판본은 냉정과 열정사이처럼 서로 다른 이야기가 아니다. ‘십만 개의 단어로 이루어진 사전 소설’이라는 부제에서 알 수 있듯, 이 책은 방대한 분량을 지녔지만 두 판본에서 다른 내용은 고작 한 문단 만큼이다. 다른 도움 없이 자기 자신의 읽기로만 다른 부분을 발견하려면 사막에서 유리구슬을 찾는 일처럼 대단히 오랜 시간이 걸릴 테지만, 다른 부분을 찾아내는 것 자체를 목적으로 한다면 그건 특별히 어렵지는 않다. 하지만 다른 부분을 찾아낸다 하더라도, 이 차이가 실로 어마어마한 결정적 차이를 산출한다는 것을 결코 즉각적으로 알아채지 못한다. 이 차이는 ‘다른 결말’을 가시적인 형태로 우리에게 보여주지 않기 때문이다.

차이 자체는 이 책이 품은 신비가 아니다. 그보다는, 티끌과 같은 차이의 공간이 일으킨 소용돌이는 가늠할 수 없이 긴 읽기의 시간 속에서 휘몰아쳐 전체를 요동치게 만들 것이고, 그제서야 다른 결말은 읽는 이에게 다다르게 될 것이다. 이 시나리오는 일반적인 독자가 감당하기에는 난감할 정도로 큰 시간 규모와 강렬한 복잡함에 대한 상상력을 요구하긴 하지만, 그럼에도 불구하고 ‘무한대에 가까운’ 서사적 픽션과 관련한 것이다. 하지만 카자르 사전의 진정한 픽션은 서사적 픽션과는 다른 자리에 할당된다. 그러면 그 픽션은 뭘까? 이 책의 맺음말에서 그 힌트를 찾을 수 있는데, 맺음말은 뜬금없이 ‘이 사전의 유용성에 대하여’라는 부제를 달고 있다. 유용성이란 다음과 같다.

“그 달의 첫번째 수요일에 이 사전을 옆구리에 끼고 도심의 광장에 있는 찻집으로 들어가라. 그곳에서는 어떤 젊은이가 당신을 기다리고 있을 것이다. 그 젊은이도 역시 외로움에 잠겨 똑같은 책을 읽으면서 시간을 헛되이 흘려보내고 있을 것이다. 두 사람은 자연스럽게 함께 차를 마시면서 그들이 가지고 온 남성본과 여성본을 서로 비교하게 될 것이다. 그 두 가지 판본은 커다란 차이점을 가지고 있다. 두 사람이 도로시아 슐츠 박사의 마지막 편지를 서로 비교할 때, 그 책은 전체적으로 완전하게 들어맞을 것이다. 마치 도미노처럼 말이다. 두 사람은 이제 더 이상 그 책이 필요없을 것이다. 만약 그렇게 된다면 두 사람은 사전 편찬자를 꾸짖어도 좋다. 하지만 다음 단계를 위하여 그런 과정은 빨리 넘어가는 것이 좋다. 다음 단계라고 하는 것은, 단지 두 사람이 연애를 하게 되는 것을 의미한다. 아무리 좋은 책을 읽는다 하더라도 그보다 더욱 값진 경험은 없다. 나는 두 사람이 거리의 우편함 위에 먹을 것이 담긴 도시락 바구니를 올려놓고, 자전거에 앉은 채 서로를 끌어안고 식사하는 모습을 그려 보고 있다.

베오그라드, 레겐스부르크, 베오그라드

1978-1983

밀로라드 파비치.”4

이것은 단연코 사랑에 관한 말이다. 저자는 십만 단어를 쓴 이후에, 이야기에 대한 어떠한 회고도, 부연도, 의미도 아닌 책의 쓸모에 대해 말하고 있고 이 책의 쓸모는 결국 사랑의 가능성과 관련한 것임을 말한다. 오직 한 권의 책에 봉합된 이야기였다면 독자는 홀로 외로이 오랜 시간을 이야기 속을 떠돌아 다녔을 테지만, 아주 사소한 차이의 공간을 지닌 두 책으로 인해 독자는 책을 들고 밖으로 나와 누군가와의 만남을 기대할 수 있는 것이다. 하나의 책이었으면 불가능했을 일. 그렇다면 나는, 앞서 『창백한 불꽃』에 관해 주장했던 것과 마찬가지로, 카자르 사전에 쓰인 글 또한 그저 ‘두 권의 책’에 소요되기 위한 것이라고 감히 주장할 수 있을 것이다.5

‘둘의 픽션.’ 둘의 픽션에 대해서 조금 더 생각해보자. [하나]와 [하나], 둘이 있으면 반드시 무슨 일이든 생겨난다. 하나와 하나가 서로 다르다면 유쾌하거나 슬프거나, 지루하거나 놀랍거나, 사랑이거나 배신이거나, 행복하거나 끔찍하거나, 희극적이거나 비극적인 다양한 이야기가 만들어진다. 거의 대부분의 이야기는 서로 다른 [하나]와 [하나]가 만나면서 형성되는 사건이다. 그런데 만약 [하나]와 [하나]가 거의 같다면 이야기는 조금 섬뜩해지거나, 불쾌해지거나, 감당하기 어려운 문제들이 터져 나오게 한다.

프로이트는 나의 모습이기도 하지만 동시에 타자로 목격되는 도플갱어가 ‘두려운 낯설음’이라는 감정을 불러 일으키는 것은 그것이 억압된 것의 회귀, 통일된 것의 반복, 자아의 분열 등 은폐되어야 할 것을 드러내는 형상이기 때문이라고 말한다. 그 형상은 억압된 것, 나조차도 인식하지 못하는 나 자신의 출현이다. 그 형상들에 서로 다른 이름을 붙이고 자신의 몸을 그들이 연기할 수 있는 무대로 삼도록 자리를 내어준 것이 다름 아닌 페소아의 기획일 것이다.6

동인이명이 만들어내는 픽션에 대해서 나는 조금 다른 관점으로 이해해 보려 하는데, 맥놀이(beat)라는 기초적인 음향 합성 현상에 대한 이해를 통해서이다.

맥놀이의 사전적 정의는 “진동수가 거의 같은 두 소리가 중첩된 결과, 규칙적으로 소리의 크기가 커졌다 작아졌다 하는 일이 반복되는 현상이다(한국물리학회, 2018).” 안타깝게도 소리 현상을 묘사하기에 텍스트는 너무 취약하지만, 다행스러운건 이 글을 읽게 될 대다수의 한국어 독자들은 맥놀이에 관해서라면 공동의 경험을 가지고 있을 가능성이 크단 사실이다. 새해를 알리는 보신각 종소리처럼 한국 전통 범종이 타종 후 ‘웅-웅-’하며 내는 여운의 소리가 바로 대표적인 맥놀이 현상이다. 범종 소리에서 맥놀이 현상이 일어나는 것은 범종의 두께를 전체적으로 균일하게 만들지 않아 타종을 하면 거의 비슷하지만 서로 다른 진동수의 수많은 울림이 동시에 일어나기 때문이다.7

여기서 중요한 것은, 맥놀이 현상이 일어나는 조건이란 ‘거의 같지만 아주 적은 차이를 가진’ 진동수들의 출현과 상호간섭이라는 점이다. 완전히 동일한 진동수의 두 소리가 울리면 우리는 그것을 한 소리로 인식하고, 유의미하게 차이나는 진동수의 두 소리가 울리면 우리는 그것을 두 소리의 중첩으로 인식한다. 거의 비슷한 진동수의 두 소리가 일으키는 맥놀이에 대해서 우리는 신비롭다고 여기기도 하지만 대개 불편함을 느낀다.

마치 무언가 잘못되었다는 듯이. 서로 다른 진동수들이 가지는 관계 양태에 대해 인간은 수많은 이름을 붙여 왔고, 맥놀이는 일반적으로 ‘불협’의 관계로 규정되어 ‘조율’되어야 할 현상으로 여겨졌다는 사실을 되돌아 본다면, 우리는 우리의 사회문화에서 ‘둘의 픽션’의 자리가 얼마나 협소한지에 대해서도 생각해볼 수 있다. 나는 이것이 우리가 [하나]와 [하나]로부터 생성되는 복수성을 상상하는 역량과 관계 있다고 생각한다.

보편 언어가 개별의 특수한 언어들에서 어떻게 나타나는지를 파악하는 비교 언어의 기획 아래, 빌헬름 폰 훔볼트는 ‘쌍수’라고 하는 문법 형식에 주목하며 이것이 여러 민족 언어에서 어떻게 상이하게 나타나는지를 고찰했다. 왜냐하면 쌍수는 분리와 결합에 관한 인간의 문제와 맞닿아 있기 때문이다. 여기서 훔볼트가 환기시키는 것은 쌍수라는 것이 단지 나열된 숫자들 중 하나인 ‘2’, 단수와 복수 사이의 중간을 위해 만들어진 ‘제한적 복수’가 아니라는 점이다.

예컨대 파라과이 지방어인 아비폰어에는 ‘두 개의 대상 그리고 좀 더 보다 많은 대상, 그러나 언제나 소량의 대상을 위한 보다 좁은 복수’가 있고, ‘많은 대상을 위한 보다 넓은 복수’가 존재한다. 쌍수는 단지 ‘2’만을 지시하는 집합적 단수가 아니다. 그것은 하나가 다른 하나와, 하나들이 다른 하나들과 구분되고 통합되는 역동과 관련한다. 다음의 말에서 우리는 ‘둘의 픽션’에 대해 조금 더 곱씹어볼 수 있을 것이다.

“쌍수는 동시에 다수 형식으로서 복수 특성을 나타내고 묶여진 전체의 명칭으로서 단수 특성을 나타낸다. 경험적으로 볼 때 쌍수가 실제 언어들에서 복수에 가까이 있다는 것은 이 두 개의 관계들 중 복수 특성이 민족들의 자연스런 의의를 더 많이 나타냄을 증명한다. 쌍수의 의미 있는 정신적 사용만이 언제나 집단적 단수의 단수 특성을 확정할 것이다. 비록 나중에 사용될 모든 생각이 쌍수에 대한 옳은 혹은 그른 생각을 서로 혼합하고, 쌍수를 통한 이원성으로서의 ‘2’의 표현으로 만들지라도 모든 언어에서 이 단수의 특성은 쌍수의 기본 원리로서 입증될 수 있다.”8

In the final paragraph of the Foreword to Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, the fictional character Charles Kinbote advises the readers of the following:

“I find it wise in such cases as this to eliminate the bother of back-and-forth leafings by either cutting out and clipping together the pages with the text of the thing, or, even more simply, purchasing two copies of the same work which can then be placed in adjacent positions on a comfortable table.”1

For those who may not be familiar with the story of Pale Fire, I will briefly explain the context from which this guideline appears. Pale Fire is a novel composed of four parts:

- “Foreword” (by Charles Kinbote)

- “Pale Fire: A Poem in Four Cantos” with the 999-line (by John Shade)

- “Commentary” on the poem (by Charles Kinbote)

- “Index” (by Charles Kinbote)

At first glance, the novel seems somewhat misleading, as it resembles the typical editorial structure of a poetry collection. However, both John Shade, the deceased American poet, and Charles Kinbote, the commentator and editor, are both fictional. Therefore,Pale Fire is Nabokov’s work of fiction, which implements the format of a poetry collection (rather than being one) within the structure of a novel.

Kinbote, who writes and edits the commentary to “Pale Fire: A Poem in Four Cantos”, advises in the Foreword against following the usual convention of reading the poem first and then the commentary, but instead to read the commentary first and then the poem. And after reading the poem, he suggests returning to the commentary to deepen one’s understanding of the poem. In other words, he urges the reader to go back and forth between the commentary and the poem.

By ‘such cases,’ Kinbote refers to the challenge of reading a codex-formatted book. To navigate this, he suggests purchasing two copies of the book to read them side by side. Although his suggestion may seem and be dismissed as a practical solution for the sake of convenience and efficiency, the true fiction of Pale Fire, in fact, originates from the concept of two books. I would even go so far as to argue that the premise of the text revolves around these two books.2

But despite the author’s sincere suggestion, how many would actually have purchased two copies of the same book to read this novel? While the question cannot be answered precisely, I am certain that the few readers who did so were introduced to a fiction that would not have been accessible to those who read it with only one copy. So, what is this fiction?

A more decisive pair of books can be found in the two versions of Milorad Pavić’s Dictionary of the Khazars, published separately in male and female editions. The third section of the book’s Preface: How to Use This Dictionary, offers a reading experience similar to that suggested by Charles Kinbote in Pale Fire.

“The reader can use the book as he sees fit. As with any other lexicon, some will look up a word or a name that interests them at the given moment, whereas others may look at the book as a text meant to be read in its entirety, from beginning to end, in one sitting, so as to gain a complete picture of the Khazar question and the people, issues, and events connected with it. The book’s pages can be turned from left to right or from right to left, as were those of the Prussian edition. The three books of this dictionary can be read in any order the reader desires.”3

As can be easily inferred from the above quotation, the Dictionary of the Khazars resembles the structure of a dictionary. Not many people would read a dictionary from beginning to end, and in order. Typically, a dictionary is briefly consulted for specific terms. Otherwise, it is flipped through aimlessly, reading whatever catches your eye before returning to the shelf. A dictionary has as many or more entries as there are words in the dictionary, and the entries are connected in all directions. In this way of reading, Dictionary of the Khazars anticipates a near-infinite narrative—an immense whole that exceeds the sum of the individual stories—and hopes that the book will be engaged for a necessarily long period of time. This aspect of the book’s fiction alone already transcends the reader’s sense of reality. However, the real issue lies in the fact that there are two books.

The two versions, male and female, of Dictionary of the Khazars are not two different stories in the same way as Between Calm and Passion is.9 As suggested by the subtitle, A Lexicon Novel in 100,000 Words, the book is massive, but the actual difference in the content between the two versions is only about one paragraph. As if looking for a needle in a haystack, it would take an incredibly long time to uncover the differences without assistance, though it would not be particularly difficult if that were the only goal. Yet, even if you can find the difference, it will not be immediately apparent that this difference results in a truly enormous, decisive change. This difference does not present a conceivable other ending to us.

The mystery of the book does not lie in the difference itself; rather, the whirlwind brought by an atomic difference would stir up the entire narrative in the unpredictably long reading time, and only then would the other ending reach the reader. This scenario sets high expectations for the casual reader and requires an imagination that can grasp its vast time scale and intense complexity. Nevertheless, it is still a matter related to a near-infinite narrative fiction. Meanwhile, the true fiction of the Dictionary of the Khazars is not assigned to the realm of narrative fiction. So, what is this fiction? The clue can be found in the closing note, which is curiously subtitled, On the Usefulness of This Dictionary. The term, usefulness, can be elaborated as such:

“On the first Wednesday of the month, with the dictionary under her arm, let her go to the tea shop in the main square of town. Waiting for her there will be a young man who, like her, has just been overcome with a feeling of loneliness, wasting time by reading the same book. Let them sit down for a coffee together and compare the masculine and feminine exemplars of their books. They are different. When they compare the short passage in Dr. Dorothea Schultz’s last letter, printed in italics in the one and the other exemplar, the book will fit together as a whole, like a game of dominoes, and they will need it no longer. Then let them give the lexicographer a good scolding, but let them be quick about it in the name of what comes next, for what comes next is their affair alone, and it is worth more than any reading. I see how they lay their dinner out on top of the mailbox in the street and how they eat, embraced, sitting on their bicycles.”

Belgrade, Regensburg, Belgrade

1978-1983

Milorad Pavić.4

This is undoubtedly about love. Having written 100,000 words, the author is not talking about a retrospective, an appendix, or a deeper meaning of the story, but about the usefulness of the book, a usefulness that is ultimately connected to the possibility of love. If it were a story contained in a single book, the reader would have wandered alone in the narrative for a long time. However, because there are two books with only a slight gap of difference, the reader can step outside and anticipate an encounter with someone else. It would have been impossible if there had been only one book. Therefore, as my previous claim about Pale Fire, I dare say that the writing in Dictionary of the Khazars is also meant for the purpose of having two books.5

Let us delve a little further into the fiction of Two. In two, one and another one, something is bound to happen. When one and one are different, various stories emerge: they may be joyful or sad, boring or surprising, love or betrayal, happy or horrible, comic or tragic. Almost all stories are created by the encounter of two different ones. But when one and one are nearly identical, the story becomes disturbing, unpleasant, or filled with unbearable issues.

Freud says that the doppelgänger, who is witnessed as both myself and the other, evokes a sense of uncanny strangeness because it is a return of the repressed, the repetition of the unified, the divided self—a form that reveals what should be hidden. This form is the appearance of what is repressed, a self which cannot be recognized as one’s own. To give these forms different names and a stage on which to perform one’s body must be nothing other than Pessoa’s plot.6

I try to approach the fiction created by doppelgängers from a slightly different perspective –by understanding the fundamentals of sound synthesis, otherwise known as beat.

The dictionary definition of beat describes it as “a phenomenon in which two sounds with nearly identical frequencies overlap, causing a regular fluctuation in the volume of the sound(The Korean Physical Society, 2018).” Unfortunately, the phenomenon cannot be better expressed in words, but rather fortunately, most Korean readers of this text are likely to share a common experience with beats. A typical example is the lingering sound that follows the ringing of the Bosingak bell, which celebrates the beginning of a New Year. It is due to the fact that the bell does not have a uniform thickness; so when it rings, several vibrations of slightly different frequencies are produced synchronously.7

It is worth noting that the beat phenomenon occurs under the condition of the appearance and mutual interference of frequencies that are ‘almost the same, but with a very slight difference.’ When two sounds with identical frequencies resonate together, we perceive them as one; and when the frequencies differ significantly, we recognize them as the overlapping of two different sounds. However, when the two frequencies are very similar, we tend to perceive the beat as either something mystical or, more commonly, annoying.

We have given numerous names to the relationships between different frequencies, and beats are generally considered as a dissonant relationship that needs to be tuned. Reflecting on this matter, we can also think about how scarce the space is for the Fiction of Two within our social culture. I believe this has to do with our capacity to imagine the multiplicity that comes from one and one.

Within the framework of comparative linguistics, which seeks to understand how the universal language manifests itself in the particular languages of individuals, Wilhelm von Humboldt focused on the grammatical form of the dual and examined how it appears differently across various ethnic languages. This is because the dual refers to the human problem of separation and union. What Humboldt emphasizes here is that the dual is not simply the ‘2’ in a list of numerals, nor is it a limited plural created for the middle ground between singular and plural.

For instance, the Abipón people, an indigenous group in Paraguay, use two types of plurals in their language: the first type of plural refers to two or slightly more objects but always for a rather small amount, and the the second is a broader type that refers to many more objects. The dual is not merely a collective plural representing a set of ‘2’; it reflects the dynamics of how one is distinguished from another and how they are simultaneously separated and integrated. In the following excerpt, we may contemplate further on the Fiction of Two.

“The dual embodies the characteristics of both the plural nature of multiplicity and the singular essence of a unified whole. From an empirical standpoint, the fact that the dual is linguistically more intimate with the plural form seems to suggest that the plural form has more cultural relevance out of the two relations. Only a meaningful, cerebral use of the dual will determine the singularity of the collective singular. Even if every idea for later use muddles the right or wrong thoughts about the dual and results in the dualism of ‘2’, this singularity can be demonstrated in all languages as the basic principle of the dual.”8

-

블라디미르 나보코프,창백한 불꽃, 김윤하 옮김, 문학동네, 2019, 35쪽.

Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire, New York: Lancer Books, 1963, p.18. ↩ ↩ -

노파심에 하는 말이지만, 이 주장은 아무 텍스트나 자리에 들어갈 수 있다는 것을 뜻하지 않는다. 오히려 ‘두 권의 책’을 가능하게 하는 텍스트란 매우 특수한 쓰기를 요구한다고 말하는 것이 옳다.

Just to be clear, this argument does not mean that any text can fit into such a position. Rather, it is more accurate to say that the text that makes two books possible requires a very specific kind of writing. ↩ ↩ -

밀로라드 파비치, 카자르 사전, 신현철 옮김, 랜덤하우스코리아, 1998, 20-21쪽. 남성판과 여성판에서 페이지는 같다.

Milorad Pavić, Dictionary of the Khazars, New York: Pantheon Books, 1984, p.5. / The pages are the same in the male and female editions. ↩ ↩ -

파비치, 앞의 책』, 374-375쪽. 남성판과 여성판에서 페이지는 같다.

Pavić, op.cit., pp.342-343. / The pages are the same in the male and female editions. ↩ ↩ -

그러므로 카자르 사전은 반드시 두 판본이 각각의 단행본으로 출간되어야 한다. 1998년 랜덤하우스에서 출간한 카자르 사전의 한국어판은 여성판, 남성판 두 판본이 모두 출간되었고 현재 절판되었다. 2011년 열린책들에서 출간된 하자르 사전은 여성판본이며, 책 말미 편집자 노트에서 남성판의 다른 내용만을 발췌해 소개해 놓았는데, 이는 카자르 사전의 가장 중요한 픽션을 원천적으로 불가능하게 만드는 치명적인 잘못이기에 가능하다면 절판된 카자르 사전의 판본을 구해 읽기를 권유한다.

Therefore, Dictionary of the Khazars must be published as two separate editions. There are instances where the differences between the two versions are compiled into a single volume, often called the androgynous edition. However, this is a critical error, as it fundamentally eliminates the core fiction of Dictionary of the Khazars. I highly recommend reading the original two editions of Dictionary of the Khazars. ↩ ↩ -

“내 안에 여러 인격을 만들었다. 계속해서 만들어내고 있다. 내 꿈들은 즉흥적이며, 꿈으로 표현되는 순간 또 다른 인간으로 구현된다. 꿈을 꾸기 시작하면 내가 아니게 된다. 창작하기 위해서 나를 부쉈다. 내면에서 나를 외재화할 수록 내면의 나는 외부가 아니고선 존재하지 않게 된다. 나는 텅 빈 무대다. 여러 배우들이 다양한 장면을 연기하며 지나간다.” 페르난두 페소아, 이명의 탄생, 김지은 엮고 옮김, 미행, 2024, 76쪽.

“I’ve created various personalities within. I constantly create personalities. Each of my dreams, as soon as I start dreaming it, is immediately incarnated in another person, who is then the one dreaming it, and not I. To create, I’ve destroyed myself. I’ve so externalized myself on the inside that I don’t exist there except externally. I’m the empty stage where various actors act out various plays.” Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, trans. Alfred MacAdam, New York: Penguin Books, 2002, p.299. ↩ ↩ -

에밀레종의 경우, 1,000Hz 이내 범위에서만 50여 가지 서로 다른 떨림이 일어난다고 한다. 자세한 내용은 다음 기사를 보라. 오철우, 성덕대왕신종 소리의 비밀 푼 ‘맥놀이 지도, 한겨레, 2019년 10월 19일.

In the case of The Sacred Bell of Great King Seongdeok, it is said that over 50 different vibrations occur within the range of 1,000 Hz. For further details, refer to the following article: CheolWoo Oh, “The Mystery of The Sacred Bell of Great King Seongdeok’s Sound Unveiled: The Beating Map”, The Hankyoreh, October 19, 2019. ↩ ↩ -

빌헬름 폰 훔볼트, 쌍수에 대하여, 언어의 민족적 특성에 대하여, 안정오 옮김, 고려대학교 출판문화원, 2017, 93쪽.

Wilhelm von Humboldt, “Über den Dualis,” Über den Nationalcharakter der Sprachen, trans. Cheungo An, Seoul: Korea University Press, 2017, p.93. *Translator’s footnote: it should be brought to the reader’s awareness that the quote has not been retrieved from an official translation of Humboldt’s thesis but privately translated from the Korean source for the lack of availability. ↩ ↩ -

냉정과 열정사이는 두 연인의 서로 다른 시점으로 쓴 ‘Blu’와 ‘Rosso’ 두 버전이 한데 묶인 소설로, 츠지 히토나리가 남자의 이야기를, 에쿠니 가오리가 여자의 이야기를 썼다.

Between Calm and Passion is a novel that consists of two versions, ‘Blu’ and ‘Rosso,’ written from the different perspectives of two lovers. Tsujii Hitorari wrote the male character’s story, while Ekuni Kaori wrote the female character’s story. ↩