안 하는 편을 택하겠습니다

앉은 자세 그대로, 나는 용건이 무엇인지 재빨리 말해주었다. 그런데 바틀비가 구석자리에서 나오지 않고 상냥하면서도 단호한 목소리로 “안 하는 편을 택하겠습니다.” 라고 답하는 것이 아닌가? 내가 얼마나 놀랐을지, 아니 당황했을지 상상해보시라.

- 허먼 멜빌, 바틀비 중에서

곰염섬은 2011년 태어나 약 1년이 채 안 되는 활동기간동안 11번의 경주를 했고, 5등 안으로는 들어온 적이 거의 없었다. 그다지 뛰어난 기량을 선보이지 못했던 진갈색의 이 말은 오로지 경주하기 위해 네 해의 짧은 생을 살다가 2015년 폐사되었다. 보통 경주마들은 ‘광폭질주’, ‘헤일로켓’, ‘태양광속’, ‘열풍’처럼 빠르고 강인한 인상을 주는 이름을 가지고 있는데, 이에 비하자면 ‘곰염섬’은 밋밋할뿐더러 속도경쟁이라는 기능에도 그다지 어울리지 않는다. 오히려 ‘섬’이라는 글자 때문인지 어느 한적한 부둣가에서 희미하게 보이는 무인도를 상상하게 할뿐이다. 곰염섬이라는 이름은 경주마의 주된 기능에 앞서거나 뒤따르지 않고, ‘그 말(馬)’을 지칭하는 고유명의 역할을 수행하는 것이다. 정지현의 개인전 제목인 곰염섬 또한 전시와의 관계에서 이와 비슷한 체계를 형성한다. 곰염섬은 단지 2016년 6월 1일부터 7월 2일까지 두산갤러리에서 진행된 전시를 지칭하는 고유명으로 기능할 뿐 그 주제나 형식을 명시적으로 부연하지 않으며, 서사적 맥락을 제공하거나 담론을 내세우지도 않는다. 그러나 다른 방식으로 전시를 부연하는데, 바로 고유명의 작동방식 그 자체이다. 이 의도적인 고유명은 조형에 의미를 접붙이는 언어를 도려내고자 이야기를 포기하겠다는 적극적이고 강력한 선언으로 읽힌다. (그리고 이야기가 의미로 안착되는 과정은 매우 관습적인 이해 안에서 작동하는 시스템이다) 그와 동시에 전시장에는 무수히 많은 ‘장치’들이 산포되어 있기에 관람객인 ‘나’가 상상할 수 있는 서사는 다른 방식으로 발생하며, 그 서사가 투사 될 장소는 임의적으로 변한다. 즉 전시장은 의미에 있어 일종의 ‘가능의 잠재적 상태’에 머물기 때문에 이 전시에서 가장 중요하게 다루어야 할 질문은 곰염섬의 장치가 어떻게 구축되는지, 그리고 무엇을 구축하는지 이다.

곰염섬의 풍경은 폐허다. 좀 더 정확히 말하자면 단번에 무너져 내린 폐허다. 오랜 시간에 걸쳐 풍화되고 조금씩 내려앉고 이끼가 껴 오래된 유물처럼 보이는 폐허가 아니라, 쓰러지고 터져나간 폐허다. 정지현은곰염섬과 같은 공간에서 열렸던 바로 이전의 전시 삼키기 힘든(2016.4.13.~2016.5.21.)에서 사용했던 가벽을 철거하지 않고 그 자리에 세워둔 채 해체했다. 합판을 도려내 바닥 한켠에 쌓아두거나 기대어놨고, 지지대로 사용되었던 두꺼운 각목 골조를 그대로 드러냈다. 비뚤비뚤하게 잘려 나간, 필시 손으로 일일이 썰어 냈을 그 절단면에서 작가가 폐허의 무게에 상응하는 육체적(manual) 노동을 기꺼이 감내했음을 읽을 수 있다. 어두운 전시장 안에서 무채색의 건축 잔해들과 살이 에일 듯한 싸구려 각목의 차가운 감각을 받아내는 건 그리 유쾌한 경험은 아니다. 이 인위적인 풍경 안에는 작가가 제작한 수많은 오브제들이 틈입해있다. 리플릿에 그려진 실루엣을 참고하더라도 웬만해선 모든 작업을 쉽사리 찾아낼 수 없을 만큼 이들은 큰 위화감이 주지 않고 폐허의 풍경에 섞여 들어간다. 때문에, 결국 이 모든 구성이 풍경이라는 하나의 강한 이미지로 수렴된다. 별다른 예민함을 곤두세우지 않는다면 곰염섬을 관람한다는 것은 일종의 가상의 폐허 속을 거니는 경험과도 같을 것이다.

그러나 작가가 만들었던 지난 작업과 전시들을 곰곰이 되짚어 보면, 곰염섬이 폐허의 감각을 주는 것 자체가 이 전시가 작동하는 역설이자 중요한 특이점 중 하나라는 것을 알 수 있다. 정지현이 만든 작업의 고유한 미감이라고 손꼽을 수 있는 게 있다면 어디선가 주워온 것들을 이리저리 붙이고 기괴하게 합친 데서 오는 조야함이라거나, 그것을 어설프다할 정도로 단순한 방식으로 미약하게 움직이게 하는 장치일 것이다. 동료 작가인 김영글은 정지현의 작업에 대한 한 리뷰에서 다음과 같이 말한 적이 있다.

“바닷가에서 쓸려 온 동물의 턱뼈, 골목길에 버려진 액자와 고장난 악기, 괘종시계에서 떨어져 나온 시계추…. 정지현은 우연히 주워 모은 사물들을 분해하고 결합해 수수께끼같은 오브제로 변형시킨다. 나름의 알고리즘을 사용해 의외의 움직임을 부여하기도 한다. 이제 사물은 원래의 이름을 잃고 명사로 형용하기 어려운 상태가 된다. 거기에는 질서와 무질서가, 우연과 필연이, 현실과 환상이 교묘하게 뒤섞여 있다.”

정지현의 작업은 폐허의 환경에 섞여 들어가기 이전부터, 버려진 물체들을 재료로 사용하고 정교함과는 먼 제작방식을 선호함으로써 언제나 위태로운 모양새를 하고 있었다. 그러나 그간 그것들이 어떤 절망의 상태나 우울함으로, 또 냉소로 읽히지 않았던 것은 작업이나 전시에서 항상 작가 스스로 제시하는 작품에 대한 배경서사가 있었기 때문이었다. 그리고 그것은 사회 속에서 살아가는 한 주체로서 감지하는 세계의 파편이자 그에 뒤따르는 휴머니즘적 실천의지였다. 예를 들어 입력된 정보에 따라 움직이는 전동휠체어 위에 설치된 탐조등이 긴 시간에 걸쳐 점멸하며 허공에 텍스트를 적어 나가는 Night Walker(2013)는, 작가의 말에 따르면 소음처럼 들려오는 라디오 뉴스에서 의미 없이 몇몇의 구절들을 따온 후 지각할 수 없는 메시지로 다시 전환시키는 작업이었다. 제각기 다른 필치의 선들이 화면을 켜켜이 채운 드로잉 연작 Thames(2012) 또한 작가가 직접 매일 탬즈강가로 나가 물결을 그리고 지나가는 배를 기록했다는 이야기가 중요하게 작동하는 작업이다. Thames는 그간 정지현이 해 온 작업의 중요한 원리를 드러낸다. 한 개인이 가늠할 수 있는 세계에 대한 손의 반응, 응대, 그리고 손을 통한 필사(筆寫). 거기에는 언제나 작업에 정향하고 있는 일종의 이야기들이 있었다. 형상에 부가된 ‘이야기’는 그 형상의 지위를 바꾸는 힘을 지닌다. 세계에 대한 감각을 수용하고 그것을 손이라는 매체(medium)를 통해 회화, 조각, 장치-오브제 등 다양한 방식으로 번역하는 일종의 ‘형상화’ 과정이 정지현이 만드는 작업의 주요한 매커니즘이었다면, 이야기는 그 작업에 대한 이해가 운신하는 폭이었다.

이번 전시에서 작가는 그간 관습처럼 부연해 오던 이야기를 지우기 위해 노력한 것이 보인다. 가벽 해체에 필요한 지난한 노동의 흔적이 첫 번째 암시라면, 두 번째 암시는 전시장 곳곳에서 발견할 수 있다. 새로이 제작된 작업들 이외에도 이전에 만들었던 작업들이 여기저기에 흩어져 있는데, 이들은 대부분 조명을 받지 못하고 전력이 공급되지 않아서 마치 박물관 유리창 너머의 오래된 유물처럼 전시되어있다. 앞서 언급했던 Night Walker의 휠체어 또한 이러한 모습으로 해체된 가벽 모퉁이에 서 있는데, 이 장치는 더 이상 빛을 내지도, 그 어떤 텍스트도 만들어내지 않는다. 의도적인 멈춤이다. 그렇다면 서사가 지워졌을 때, 남는 것은 무엇인가? 우리가 인지할 수 있는 것이라고는 정녕 폐허의 풍경밖에 없는 것일까? 그 말은, 서사가 이 세계를 지탱하고있던 일말의 풍요로움이었단 말인가? 그러나 조금만 더 감각을 예민하게 곤두세운다면, 이 질문에 쉽게 긍정하기는 힘들 것이다. 왜냐하면 곰염섬은 이야기를 비워 낸 자리에 더 복잡한 상황을 직조해놓고 있기 때문이다.

전시장을 거니면 문득 기이한 시간감각을 느낄수 있다. 정확히 위치를 파악하기 어려운 어디에선가(여러 곳에서) 형언할 수 없는 기괴한(여러 가지의) 소리가 들린다. 이들은 전시장 곳곳에서 장치-오브제가 만들어내는 소리다. 진열대에 놓인 손바닥만 한 기계에는 메뚜기 다리처럼 가느다란 구리철사가 늘어뜨려져 있는데, 이것은 일정한 주기로 들어 올려졌다가 힘없이 툭- 하고 떨어진다. 장난감에나 들어갈법한 손가락 한마디정도의 작은 모터가 내는 진동, 그리고 쇠의 마찰 소리는 규칙적이다. 콘크리트 돌이 숫자를 세는 곳은 일명 아시바라 불리는 철제 비계가 짧게 잘려 얽혀있고, 그 주위로 주먹보다 조금 더 큰 콘크리트 돌덩어리들이 어지러이 널부러져 있는 작업이다. 이 각각의 돌에는 여섯 자리까지 숫자를 셀 수 있는 플라스틱 계수기가 갯바위에 붙은 조개껍질처럼 심어져 있는데, 이들은 모두 전선으로 연결되어 스스로 숫자를 세어 나간다. 열 개가 넘는 계수기들은 한데 운집해 있고 모두 같은 소리를 내며 작동하지만, 그 소리는 서로 다른 박자로 인해 일치되지 않고 저마다의 지속(duration) 안에서 움직인다. 여섯 자리의 숫자가 표현 가능한 모든 경우의 수를 지켜보는 것, 그리고 그 숫자가 군집 안에서 어떤 공통된 규칙을 발생시키는지 발견하는 일은 인간의 물리적 조건 안에서는 거의 불가능에 가까운 일이다.(숫자가 1초에 하나씩 움직인다고 쳐도 여섯 자리의 숫자가 차오르는 것을 모두 지켜보는 일은 산술적으로만 278시간이 걸린다. 심지어 숫자는 초단위보다 늦게 움직인다) 단지, 계수기들의 소리가 분절시키는 시간과 그 각각의 시간의 중첩을 경험할 수밖에 없다.

바람이 불지 않으면은 작업의 제목과는 다르게 실제로 바람이 불게 작동하는데, 이 바람은 지속적으로 발생하는 것이 아니라 다른 장치-오브제들과 마찬가지로 일정한 간격(interval)을 두고 간간이 뿜어져 나온다. 오브제 위에는 십여 개의 철사가 불안하게 매달려 있고, 철사 끝의 은박스티커는 바람을 맞고 흔들거린다. 흔들리는 철사는 그것을 둘러싼 구리 링에 맞닿게 되는데 그 순간마다 전류가 연결되어 나무막대기에 달린 전구에 불이 들어온다. 불규칙한 철사의 움직임 때문에, 바람이 부는 간격은 일정하지만 빛이 점멸하는 지속의 시간은 매우 임의적이다. 하나의 큰 철제 구조물 속에 기능적으로는 전혀 쓸모없는 재료들로 가득 들어찬 공공선은 몇 가지 규칙적인 소리의 작동을 포함한다. 둥글게 말려 구조물 윗면에 부착된 철판과 바로 옆에서 타원을 그리며 움직이는 긴 철사가 맞닿을 때마다 낯선 쇳소리가 짧게 지속된다. 그 소리는 측정할 수 있는 차원에서는 규칙적이지만, 알 수 없는 외부적 조건으로 인해 소리의 주기에서 아주 미세한 지속의 두께 차이를 드러낸다. 구조물의 아래쪽 안에는 작은 모니터가 부착되어 있고, 그 앞에는 또한 일정한 간격을 두고 소리를 내는 장치가 설치되어 있다. 이 장치는 약 30초마다 “딱!” 하는 큰 소리를 내는 유압모터와 목재의 조합으로 만들어져있다. 그러나 마찬가지로, 이 30초라는 간격 또한 임의적인 것이었다. 어떨 때는 31초가 걸리기도 했고, 28초 만에 소리를 내기도 했다.

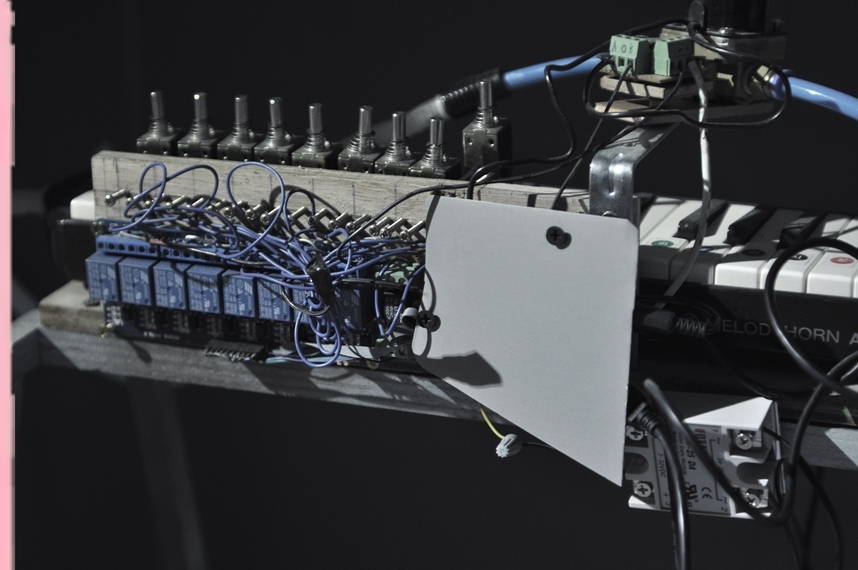

앞서 언급한 장치들이 의식을 집중해 관찰하지 않으면 그냥 지나쳐버릴 정도로 미약하게 작동했다면, 전시장 전체를 지배할 만큼 명확하고 강력한 소리 또한 존재한다. 통고동은 주변에서 흔히 볼 수 있을법한 대용량 액상세제 통에 초록색 우레탄을 두껍게 덧씌운 오브제이다. 통고동은 언뜻 보기에는 그저 의미 없이 서있는 물체이지만, 약 20분의 간격으로 전시장 전체를 울릴 만큼 큰 뱃고동소리를 낸다. 전시장의 한쪽 구석 천장에는 이 전시에서 가장 스펙터클한 장면을 연출하는 종이 낙하 장치가 설치되어 있다. 12개의 종이 분사 장치는 “빛과 중력의 계약을 잊지 않기로 / _년_월_일_시” 라는 텍스트가 형압된 흰색 종이를 허공에 흩뿌리는데, 그 간격은 바로 아래 설치된 멜로디언의 소리에 발맞춘다. 대용량 콤프레셔에 연결된 기계장치는 일정한 시간에 따라 멜로디언에 공기를 주입함과 동시에 건반을 누르도록 설계되었고, 9개의 누름쇠는 매번 조합을 바꾼다. 이 장치는 2014년 플라토미술관에서 전시할 당시 그 간격이 8분이었다는 기록이 있으나, 곰염섬에서는 13분으로 늘어났다. 통고동, 그리고 종이 낙하 장치와 함께 작동하는 멜로디언의 소리는 매우 명확하게 새로운 시간성을 창출한다.

이처럼 곰염섬의 장치들은 반복적인 움직임과 소리를 통해 여러 종류의 시간성을 만들어낸다. 그러나 여기서 중요하게 짚어야 할 지점은, 단지 인위적인 여러 시간의 단위가 존재한다는 것이 아니라 곰염섬에서 그 인위적인 시간성이 작동하는 방식이다. 나는 전시를 여덟 번 방문했었고, 세 번째 방문할 때부터 여러 오브제가 만들어내는 시간에 관심을 기울이게 되었다. 그리고 여러 방식으로 시간을 측정했는데, 하루는 초침 시계로, 하루는 디지털시계의 스톱워치로, 그리고 여러 번은 발걸음 등의 몸을 이용하거나 ‘직감’으로 시간의 간격을 파악해보았다. 그리하여 종국에 내린 결론은, 이 공간의 시간은 결코 ‘측정할 수 없다’ 였다. 내가 수차례에 걸쳐 전시장을 찾을 수밖에 없었던 이유는 매 번의 경험을 정보화시켜 빠진 퍼즐의 부분을 맞추듯 좀 더 온전한 결론에 도달하기 위해서가 아니라, 매 번이 명확하게 ‘달랐기’ 때문이었다. 이는 ‘같은 강물에 발을 두 번 담글 수 없다’같은 선형적 시간의 불가역성을 의미하는 것도, 관람자의 ‘현재’적 감각에 따라 달리 지각되는 수행적인 작업이라는 의미로 귀결되는 것도 아니다. 곰염섬은 매우 감지하기 어려운 미묘한 시간의 두께를 이용하기 때문에, 언제나 갱신되는 허구적(fictional) 세계를 조건화한다.

서사를 폐위하고, 온갖 수공적 장치-오브제의 작동만을 가시화시킨 이 실천을 허구(fiction)를 예비하는 것으로 파악하기 위해서는, 가상(virtual)이라는 개념과 대비시켜보아야 한다. 곰염섬이후 같은 공간에서 열렸던 나뭇가지를 세우는 사람(2016.9.7.~2016.10.8.)은 전시장 전체를 일종의 공원처럼 조성해 놓았던 전시였다. 갤러리의 문을 열고 들어서면 숲의 광경이 펼쳐진다. 바닥에는 흙이 아니라 나무의 파편들이 두텁게 쌓여있는데, 이 지형은 명확하게 현실의 공간과 숲의 세계가 나뉘어져있음을 선언한다. 관객은 인공적으로 조성된 길을 따라 걷게 되고, 어색하게 놓여있는 의자나 침대에 누워 휴식을 취할 수 있다. 그리고 그곳을 돌아 나와 한 발 밖으로 내딛는 즉시 그 세계는 사라진다. 환경으로 그럴싸하게 조성된 물리적인 가짜 세계는 마치 하나의 상품처럼 관객을 매개하며, 이는 일종의 페티시로만 기능할 뿐이다. ‘가상’ 이라는 것이 이미 주어진 완결성이라면, 허구적인 것은 발생하는 것이라고 볼 수 있을까? 때문에 허구적인 것은 그것이 발생하는 조건이 매우 중요하게 여겨져야 한다.

현대의 기술문명, 산업사회가 여러 분야에서 비가시적이고 비지각적인 차원에서까지 정밀함을 달성하려는 방향으로 열렬히 진보해온 것과 달리, 정지현의 장치들은 한눈에 보기에도 조야하고 어설프다. 그러나 바로 그러한 특성으로 인해 곰염섬의 공간은 기묘한 시간의 두께를 만든다. 입력된 정보값으로 작동함에도 불구하고, 각각의 장치는 분명한 스스로의 오차를 드러낸다. 움직임과 소리가 지속되는 시간은 엄격하게 일정하지 않고, 그것이 반복되는 주기 또한 아주 미약하게 변한다. 이는 이미 노후화된 재료들이 엄정하게 조립되어 있지 않은 탓에 발생하는 물리적인 필연성이며, 이 장치들은 지속적으로 스스로 노후화되길 요청한다. 바로 이것이 영원히 불안정한 시간의 두께, 혹은 끊임없이 흔들리는 시간의 운동성을 만들어내는 이유이다. 그리고 하나의 지속이 불안정하다는 것은 그것이 속한 체계에 대한 불안을 야기한다.

미국 구조영화의 계보에서 상징적인 위치를 점하고 있는 홀리스 프램튼(Hollis Frampton)의 대표적인 작업 중 하나는 초른의 보조정리(Zorn‘s Lemma)일 것이다. 1시간에 가까운 이 영상은 크게 세 부분으로 나뉘어져있는데, 약 45분정도의 가장 긴 중간부분은 대체적으로는 그 법칙을 준수하지만 약간은 임의적인 알파벳의 순서에 따라 해당하는 알파벳에 관련된 이미지들을 보여준다. 예를 들어 ‘d’의 순서에서 ‘delight’라고 적힌 간판을 찍은 화면을 보여주는 식이다. 이 진행은 반복되며 이어지지만, 마치 특정한 규칙이 정해진 것처럼(그러나 그것이 무엇인지는 영상 안에서 끝내 정확하게 파악할 수 없다) 알파벳은 어느 순간 하나둘씩 전혀 연관 없는 이미지로 대체되고, 종국에는 모든 알파벳이 제각기 다른 이미지로 대체되며 끝이 난다. 프램튼이 사용한 모든 쇼트는 짧기는 하지만 연속된 프레임으로 이루어져 1초라는 지속시간을 지닌 무빙 이미지이다. 이 작업에 대한 다른 모든 논쟁점들은 차치하고, 1초라는 짧은 시간동안 지속하는 쇼트에 대한 지각은 곰염섬안에서의 시간, 혹은 움직임에 대한 감각적 경험과 매우 유사하다. 그 이유는 명시적인 1초라는 단위가 실은 매우 미묘한 차원에서 다른 두께를 지니고 있기 때문이다. 피터 지달(Peter Gidal)과의 긴 인터뷰의 첫 부분에, 프램튼은 이 영상작업이 어떤 면에서는 “시간이라는 요소를 다루는” 것임을 단호하게 말한다. 그리고 이어 “모든 쇼트가 1초이긴 하지만, 사실은 모든 쇼트가 1초는 아니다.”라고 밝힌다. 이 영상을 구성하고 있는 이미지 중 열두 개는 23프레임짜리이며, 스물네 개는 25프레임으로 연결되어 있다는 것이다. 1초라는 단위를 기준으로 ‘유연한 간격(elastic interval)’을 보여주는 이 상태는, 프램튼의 말에 따르면 필연적인 “실수(mistake)”이자 시스템의 “오류(error)”다.

초른의 보조정리에서 그러한 오류가 가능했던 이유가 프레임의 연쇄로 이루어진 필름이 작업의 기반 요소로 사용되었기 때문이라면, 곰염섬의 경우에는 모든 움직이는 장치가 직접적으로 ‘손’에 의해 불안하게 만들어졌기 때문일 것이다. 모호한 경계가 일종의 오류라면, 그것은 공고한 시스템의 외연을 역으로 드러내준다. 이러한 관점에서 보면 곰염섬은 단지 서사를 비워낸 자리에 오작동하는 장치만 작동하는 곳이 아님을 알 수 있다. 지속에의 개입에 비해 약간은 의문으로 남는 요소들이 몇 있는데, 대표적으로 거의 아무런 정보를 담지 않은 이미지를 전시장 속에 집어넣은 방식을 들 수 있다. 기다란 비계가 두 발을 벌린 거치대 모양으로 연결된 더 빅을 자세히 들여다보면, 해가 지는 바닷가의 풍경을 매우 통속적으로 묘사한 일러스트레이션, 자동차의 3D 모델링 등 키치적인 스티커가 덕지덕지 붙어있다. 이것은 손수 잘라내 약간은 부정확한 자그마한 사각형의 거울이 미러볼의 표면을 정갈히 뒤덮은(그러나 역시나 불규칙한 틈으로 벌어진) 불화에서 볼 수 있는 이미지 중 일부다. 불화에 붙은 네모 거울 위에는 그 크기에 맞게 잘려진 수많은 이미지가 또한 하나하나에 꼼꼼히 붙어있다. 그리고 앞서 말한 키치적인 이미지 외에도 무엇인지 알 수 없는 폐쇄회로TV 캡처장면, 스마트폰 메신저에서 주로 사용하는 (작가가 직접 만든)이모티콘의 이미지들이 있다. 같은 종류가 여러 번 쓰이기도 했지만 어떤 규칙을 통해 붙어있는지 알 수 없으며, 구체 위에서 이들은 기준이 없는 듯 방향을 제각각으로 둔다. 미러볼의 한 꼭짓점에는 고리가 달려 있고 거기에는 자그마한 모터가 연결되어 주기적으로 움직이게끔 되는데, 원래는 원운동을 해야 하는듯하나 모터가 붙은 판자가 그 움직임을 방해하면서 그저 좌우로 아주 약간씩 굴릴 수 있을 뿐이다. 출처를 알 수 없는 익명의 이미지는, 미러볼 위에서, 아주 미시적인 차원에서 말 그대로 이리저리 움직인다.

서사가 완전히 사라진 진공과도 같은 상태에서 작가의 손으로 만들어진 장치, 그리고 모호한 형상의 오브제와 이미지들은 관객으로 하여금 일종의 불안을 느끼게 만든다. 이 불안은 놀이기구를 탔을 때와 같은 물리적인 불안정함(unstable)도, 심리적인 불안감(anxiety)도 아니다. 그렇다면 무엇이라 할 수 있을까? 전시장에는 하나하나 지각하거나 묘사하기에는 너무나도 정보가 많다. 앞서 언급했던 요소들 이외에도 제각기 다른 방식으로 잘려나간 나무, 복잡하게 접합된 철제 구조물, 기능과는 상관없이 마구잡이로 얽혀있는 전선뭉치의 미감은 형용하기 힘들다. 만약 이를 모두 파악하려 한다면, 이 장소는 거의 무한에 가까운 시간을 요구한다. 때문에 곰염섬이라는 고유명은 어떤 방식으로든 ‘이러저러한 것’으로 임의적으로 규정될 수밖에 없다. 그러나 곰염섬의 상태가 특징적인 것은 선택되지 못한 것들이 제거되어 사라지지 않고 엄연히 ‘꺼슬꺼슬한 무언가’로 존재한다는 것이다. 엄연히 존재하는 그 무언가가 사라지지 않고 가능세계로 인식될 수 있는 것은 분명 서사가 안내하는 간명하고 평편한, 봉합된 가상이 해체되었기 때문일 것이다. 말하자면 곰염섬에는 온갖 것들이 위계 없이 들어차있으며, 만약 거기에 위계가 생긴다면 그것은 관객의 선택의 결과일 뿐일 테다. 결국, 불안이란, 모든 가능이 전면화 될 수 있도록 조건화 된 장소에서 전적으로 주체적인 선택을 수행해야 하는 압력의 다른 이름일수도 있으나, 더 정확히 말하자면, 선택 이후에도 (사라지지 않고)여전히 가시적으로 남아있는 바로 그것들의 현현이다. 반복적이라 해도 무방할 소리와 움직임이 실은 매우 미시적인 차원에서 불안정하게 진동하며 무수한 지속을 포함한다는 감각은, 그것이 절대로 하나의 시스템으로 수렴하지 않는 상태라는 점에서 정확하게 이 불안과 연결될 것이다. 곰염섬에서는 관객에게 주어진 선택에의 압력이 꽤나 강하기 때문에 어떻게 보면 과하다싶기도 하지만, 하나의 상(象)을 종용하지는 않는다. 나는 곰염섬의 모든 과정 자체가 하나의 은유라고 생각하는데, 그것이 참조하는 것은 픽션이 아니라 픽션이 만들어지는 방식 그 자체다.

이번 전시는 작가의 현실인식과 세계를 대하는 태도가 바뀌었음을 말하지 않는다. 오히려 작가로서 세계에 어떻게 개입할 것인지, 즉 그간 해왔던 것과는 다른 예술적 실천의 방식을 실험했던 장소처럼 보인다. 곰염섬이 기능했던 전모를 돌이켜보면, 일종의 무한과 유한의 변증법적 작용에 대한 고민을 불러일으킨다. 거칠게 말해, 무엇이 어떻게 무한을 재구성하는가에 대한 질문일 것이다. 만약 서사가 무한을 통합하는 하나의 방식이라면, 이는 어느정도 한나 아렌트(Hannah Arendt)가 말하는 “망각의 구멍”과 상통할 것이다. 반면, 중압감을 수반하기는 하지만, 가능의 잠재적 상태에서 취사선택된 서사의 조각은 그것이 하나의 의미로 환원된다 하더라도 다른 존재의 가능성이 명백하도록 남겨둔다. 전자는 언제나 성공적인 것처럼 보이기에 의기양양할 수 있지만, 후자는 완결되지 못하는 것이기에 언제나 실패를 인정할 수밖에 없다. 차이는 단순하다. 유한의 잉여가 어디로 갔는가? 이는 역사를 어떻게 재구성할 것인가의 문제와 맞닿기에 지금 현재의 우리에게 매우 중요한 질문이 될 것이다. 서사가 역사를 함몰시킬 때, 그것은 어떤 잉여를 발생시키는가. 한발 더 나아가보면 이런 질문이 떠오른다. 역사는 어떻게 구성되어야 하며, 어떤 픽션을 요청하는가? 물론 여기서 역사는 지금 당장의 현재 또한 포함한다.

…I called to him, rapidly stating what it was I wanted him to do….

Imagine my surprise, nay, my consternation, when without moving from his privacy, Bartleby, in a singularly mild, firm voice, replied, “I would prefer not to.”

- Herman Melville, Bartleby the Scrivener

Gomjumsum was born in 2011. During just less than one year of his racing activities, he ran in 11 races and has never reached within 5th place of winning. Without having demonstrated particularly any outstanding skills, this dark brown horse lived a very short life of just four years, dedicated to racing, and died in 2015. While most racing horses are given names that give them an impression of power and speed like ‘Scamper’, “Hail Rocket’, ”Ray of Light’ or ‘Fever’, the name ‘Gomyomsom’ is not only boring in comparison, it doesn’t really go well with the concept of speed in competition. Perhaps it’s because of the ‘sum’ in the name (which means ‘island’ in Korean), it conjures up the image of an uninhabited island faintly visible from a quiet dockside. The name Gomjumsum doesn’t add nor takes away the function of the racing horse; it merely serves its function as the proper noun of ‘a horse’. Gomyomsom, the title of Jihyun Jung’s solo exhibition, is similar in system in terms of its relationship with the exhibition. Gomyomsom merely functions as the proper noun for an exhibition taking place at Doosan Gallery from June 1st to July 2nd, 2016, and it doesn’t explicitly magnify its subject or form, nor provide a narrative context or assert any discourse. However, it amplifies the exhibition in a different way, which is the very operation method of this proper noun. This intentional use of proper noun reads as an assertive and passionate declaration to give up the narrative in order to remove the language which endows meaning to sculptural form (and the very conventional process of understanding through which the narrative duly reaches meaning). In addition, countless ‘mechanisms’ are scattered throughout the gallery, so the narratives which ‘I’ as the audience can imagine is produced in different ways, and the places where such narratives are projected change arbitrarily. In other words, because the exhibition space has a meaning and remains in a type of ‘a state of dormant possibility’, the following questions must be asked with utmost importance in the exhibition: How were the mechanisms of Gomyomsom constructed, and in turn, what do they construct?

Gomyomsom looks like a ruin. Precisely speaking, it looks like a ruin from a total immediate collapse. It’s not like an old relic that’s covered in moss and weathered down during a long period of time; it’s a complete breakdown and blast. Jung used the walls from the exhibition Unswallowable (April 13 – May 21, 2016), which preceded Gomyomsom in Doosan Gallery, leaving them in place and tearing them apart instead of taking them down. He cut out the walls, piled the pieces on the floor or leaned them against the walls, and exposed the thick wooden structures used as the support fixture. In the jagged ruptured planes which the artist must’ve cut out himself by hand, one can see how he endured the manual labor corresponding to the weight of the ruin. It mustn’t have been a pleasing experience to handle the cold feelings of the neutral-colored architectural debris and the cheap piercing cold lumber in the dark exhibition space. This artificially constructed sight is interspersed with countless objects the artist produced himself. They aren’t incompatible with the ruin, but intermingle perfectly with the scene of the ruin to the degree that they’re not easily spotted even if one referred to the outlines of the objects drawn on the exhibition leaflet. Thus all compositions converge into one strong image of a scene in the exhibition, and the experience of exhibition is like browsing through a type of imaginary ruin.

However, upon close observation of the artist’s previous works and exhibitions, one realizes that a very important characteristic as well as the paradox of this exhibition lies in the fact that Gomyomsom is perceived as a ruin. A rare aesthetic trait of Jung’s work would be the crudeness that comes from the bizarre assemblage of things found from here and there, or the mechanisms that make them move subtly in simple and awkward ways. Young-gle Kim, Jung’s colleague, asserted the following in a review abut Jung’s work:

“Jung breaks down then combines objects he happens to collect — from castaway animal jaw bones, frames and broken instruments discarded in alleyways, or pendulums fallen from striking clocks — and transforms them into riddling objects. He applies the algorithm in his own way to endow unexpected movement. Then the object loses its original term and transforms into something which can be described in a noun. Elements of order and disorder, coincidence and necessity, and reality and fantasy are artfully combined in his work.”

Jung’s works have always been imbued with a sense of instability, because he uses discarded objects as his material and applies a method of artmaking that’s far from being exquisite or delicate. But they were never read as a state of despair, depression or cynicism because there was always a background narrative which the artist himself proposed in his work or exhibition. These works are like fragments of the world the artist observes as a subject of the world, and a form of actual visual manifestation of such observances. For instance, in Night Walker (2013), a searchlight installed on a moving electronic wheelchair flickers and writes text in mid-air following the entered information. According to the artist, this work took a few meaningless phrases from the radio news which he heard in the background noise, then transformed them into imperceptible message. In the same manner, what functions as an important element in Thames (2012) — a drawing series which lines of different textures fill the surface — is the narrative background that the artist went to the Thames river every day to draw the surface of the water and boats passing by. Thames demonstrates a crucial principle in Jung’s work so far: that a type of narrative which directs the work from a distance lies in the manual response, or transcription, to the world as measured by an individual. ‘Narrative’, endowed upon form, has the ability to change the power of the form. While the visual manifestation process — translating the perception of the world into various forms of painting, sculpture, and mechanism-objects through the medium of the hands — is an important aspect in Jung’s work, the narratives function as a conveyor which stirs the understanding of his work.

What’s evident in this exhibition is the artist’s efforts to obliterate the narrative he’s always habitually amplified. The first example of this can be found in the traces of labor executed to break down the walls, and other examples can also be found throughout the exhibition space. Besides the artist’s new works, his previous works are placed throughout the gallery. Most of them are not in the spotlight nor supplied with electricity, so they’re exhibited like ancient relics beyond the museum glass case. The wheelchair in Night Walker, mentioned above, also stands like this on the corner of the destroyed wall, no longer radiating light nor creating any text. It’s been stopped deliberately. Then what remains when the narrative has been erased? Is the ruin the only thing left which we can perceive? Does that mean that the narrative was the touch of richness which sustained the world? With slightly keener senses, it would be difficult to answer affirmatively to this question because Gomyomsom weaves out an even more complex situation in the space where narrative has been removed.

There’s a strange sense of time in the gallery. (Several) strange indescribable sounds can be heard in (a few) indefinite places that are difficult to locate. These sounds are created by mechanism-objects located throughout the exhibition space. The hand-sized device on Display has thin copper wires drooped down like the legs of a grasshopper, and these legs rise up in a fixed interval of time, then drop down. The vibration of a small motor the size of a finger which seems to have come out of a children’s toy, and the friction sound of metal are heard also on a fixed interval. In Where Concrete Stones Count, metal scaffold is cut into shorter pieces and tangled up, and concrete lumps slightly larger than fist are randomly scattered around it. A plastic scale capable of counting up to 6 digit numbers on their own is embedded into each of the concrete lumps like rock barnacles, all connected with electric wires. The scales, over ten in quantity, are all gathered in one place and produce the same sound, but each scale produces in its own rhythm and duration. Observing all the numbers expressed in 6 digits and discovering the common law of the numbers in a group is almost a humanly impossible task. Observing all the scales count up to all six digits would take 278 hours, given that the observer counts one number per second. But even then, the actual number counts slower than in seconds. The audience can only experience the time segmented by the scales and the overlapping of such segments of time.

Contrary to its title, the wind actually does blow in the work If Wind Doesn’t Blow. This wind isn’t constantly generated but, like other mechanism-objects, intermittently produces wind in set intervals. A dozen or so wires hang over the object and the silver sticker at the tip of the wires quiver with the wind. The shaky wires make contact with the copper rings that surround them, and whenever the contact is made, electricity is passed and the lightbulb on the wooden stick comes on. The interval of the wind blowing is regulated but the time the light remains on is very arbitrary. OOsun, a huge steel structure filled with completely useless material in terms of function, produces a few sounds on regular set of time. Short strange metallic sounds are generated every time a long piece of wire drawing circles makes a contact with the rolled-up steel plate on top of the structure right next to the wire. While this sound audibly seems regular, a very subtle and persistent difference is sensed in the cycle of the sound due to unknown external conditions. There is a small monitor affixed at the bottom of the structure, and in front of it is a mechanism which makes sounds on a fixed interval of time. This mechanism consists of a hydraulic motor and wood which makes a loud striking noise every 30 seconds. This interval, however, is also arbitrary: sometimes it takes 31 seconds, and sometimes it takes 28 seconds.

While the mechanisms mentioned above operated in such a subtle way that they were almost unrecognizable without paying a close attention, there were also loud and clear sounds in the exhibition which dominated the entire space of the gallery. Green Horn is a common bulk-sized detergent bottle coated with a thick layer of green urethane. At a glance, it seems to stand in space without any meaning, but it sounds a foghorn throughout the gallery roughly about every 20 minutes. In one corner of the gallery is Paper Drop Apparatus which creates the most spectacular scene in the exhibition. Each of the 12 paper dispersing devices drop sheets of white paper with the text “Let’s not forget the contract between light and gravity / _year_month_date_time” pressed into the paper, in an interval of time set to the sound of the melodeon installed underneath it. The mechanical device connected to the bulk compressor inserts air into the melodeon and presses its keys at a fixed interval of time, and the combination of the 9 pressers changes each time. It’s recorded that the interval of time in the sounding of this device was 8 minutes when the work was shown in PLATEAU, Samsung Museum of Art in 2014, but it increased to 13 minutes in Gomyomsom in Doosan Gallery. Together with Green Horn, the sound of the melodeon, activated with Paper Machine, clearly creates a new sense of time.

Gomyomsom creates different types of temporality through the repetitive sounds and movements of the devices. However, the important point lies not in the fact that many arbitrary units of time exist but the very way in which such arbitrary temporality operates in the exhibition. I visited the exhibition 8 times, and from the third visit I started to become interested in the sense of time created by several mechanisms. I also measured time through various ways: one day using a watch with a second hand, another day with a stopwatch in digital clock, and in many times, I tried to read the interval of time through my instincts, using my physical body such as my footsteps. And my final conclusion was that the time in this space ‘can never be gauged’. The reason I had to come to the exhibition so many times was not because I wanted to transform every experience into information and arrive at a more complete conclusion as if to put pieces of a puzzle together; it was because the show was clearly ‘different’ every single time. This doesn’t signify the irreversibility of linear time, nor does it conclude to mean that it is a performative work which is differently perceived through the ‘present’ perception of the audience. Gomyomsom deals with a very delicate thickness of time which is very difficult to perceive; therefore, a fictional world that’s always renewed is conditioned in the exhibition.

The narrative is obliterated and only the operations of all sorts of handmade mechanisms and objects are visible. In order to take this as a preliminary to fiction, it must be juxtaposed with the concept of the virtual. Held in the same space in Doosan Gallery after Gomyomsom, the exhibition Putting up Tree Branches transformed the entire exhibition space into a park. The woods unfold upon opening the doors of the gallery. Pieces of wood, as opposed to soil, are placed in a thick layer on the floor of the gallery, and this clearly declares that the space of reality and world of the woods are distinctly separated. The audience walks along the artificially staged path, and can even take a rest on the chairs and beds that are awkwardly positioned throughout the exhibition. However, this world immediately disappears the very moment the viewer turns around and takes a step outside of the gallery. The physical fake world, made to mimic reality through constructed environment, mediates like a commodity, and functions merely as a type of fetish. If ‘virtual’ was an already-given completion, then should the ‘fictional’ be regarded as something that is produced? In this sense, the very conditions through which the ‘fictional’ is produced must be considered an imperative factor.

Contrary to how today’s technological civilization and industrial society has fervently progressed to reach perfection in all fields even to the non-visible and non-perceptive dimensions, Jung’s devices are evidently rough and clumsy. This special quality, however, is what produces the strange thickness of time in Gomyomsom. Even though they operate according to the input information, each of the devices demonstrates definite errors. The time of movement and sound is not strictly steady, and its interval of repetition also varies slightly. Such is the result of physical inevitability which comes from old materials being put together not in the most precise way, and these devices also demand themselves to continue the deterioration. This is what causes the thickness of eternally unstable time, or the dynamism of perpetually quivering time. And the fact that a continuation is unstable gives rise to our unrest towards the system to which it belongs.

Zorn’s Lemma is one of the most representative works by Hollis Frampton, a forefather of American Structural Films. This film, with a running time close to one hour, is largely divided into three parts. The middle part — which is the longest part at approximately 45 minutes — follows the rules for the most part, but according to the arbitrary order of the alphabet, it shows images related to the applicable alphabet. For example, for ‘d’, it shows a board with the word ‘delight’ on it. This process is repeated, but as if a particular regulation is decided (this cannot be apprehended in the film, however), the alphabets suddenly start to be replaced one by one by completely irrelevant images, and in the end, all alphabets are replaced by different images. All the shots used by Frampton are short but they are moving images that last for the duration of 1 second, which are made of a continuation of frames. Putting aside all other issues of argument about this work, the perception of the shot which lasts for the very short period of 1 second is very similar to the time, or the perceptive experience of movement in Gomyomsom. This is because the clear unit of 1 second actually has a different thickness in a very subtle dimension. At the beginning of a long interview with Peter Gidal, Frampton asserts that this film in a way “deals with the element of time”, and continues to say that “while all shots are 1 second, they are actually not 1 second.” This means that each of the 12 images that construct this video consists of 23 frames per second, and the other 24 images each consists of 25 frames per second. According to Frampton, this state, which demonstrates ‘elastic interval’ in the unit of 1 second, is an inevitable “mistake” or “error” in the system.

Such errors were possible in Zorn’s Lemma because the film, consisting of a series of frames, was used as the basic elements of the work. In the same way, such errors are possible in Gomyomsom because all moving mechanisms were made unstable, directly through the ‘hands’. If the imprecise boundary is a type of error, it in turn demonstrates the scope of firm and stable system. In this perspective, it’s evident that Gomyomsom is not only just about filling the space where narrative has been removed with operations of devices that continue malfunctions. There are a few elements that remain as questions, and one of them would be that images with almost no information are put into the exhibition space. Upon closer inspection of The Big, in which two long scaffolds are connected like a stand with its legs open, it’s covered with kitschy stickers of cliché illustrations of sunset ocean views and 3D modeling of automobiles. This is a part of the image in the work Quarrel, in which small rectangular mirrors, imprecisely cut by hand, are plastered (with irregular gaps) onto the mirror ball. On the rectangular mirrors in Quarrel, countless images are cut accordingly in size and meticulously glued to each mirror. Other than the kitschy images mentioned above, there are also unidentifiable images captured by surveillance cameras and images of emoticons (made by the artist himself) used in smartphone messages. Although the same types were used many times, it’s difficult to tell what rules they follow, and they hover in their own directions without any standards. There is a loop on one vertex of the mirror ball, and it’s connected to a small motor which makes it move periodically. While it’s supposed to move in a circle, the plank on which the motor is affixed disturbs this movement and makes it move slightly to left and right. The indistinctive images with unknown sources move here and there (literally) on top of the mirror ball in a very microscopic dimension.

In the vacuum-like state without a single narrative, the artist-made mechanisms and completely ambiguous objects (and images) stir up a feeling of unrest in the viewer, which isn’t like a psychological anxiety nor unstable physical sensation of riding an amusement park ride. Then what is this feeling of unrest or uncanniness? There is too much information in the exhibition to be singularly perceived or described. Besides the elements mentioned above, it’s difficult to describe the sense of beauty in the woodcut up in all directions, steel structures that are complexly grafted together, and the piles of electric lines that are tangled up for no apparent reason. To apprehend everything in the exhibition, this place would demand an almost infinite amount of time. Therefore, the proper name ‘Gomyomsom’ can only be arbitrarily fixed as ‘this and that’. However, what characterizes Gomyomsom is that the unselected is not removed and remains undoubtedly as ‘something there’. Something which undoubtedly exists can remain and be recognized as a possible world, probably because the simple, plain and sealed virtual world, which the narrative introduces, has been broken down. In other words, all sorts of things without hierarchy fill Gomyomsom, and if there were to be a hierarchy, it would only be imposed upon by the viewer. Ultimately, anxiety might be another term for the pressure to make completely independent decisions in a place where all possibilities are conditioned to be displayed in full at once. More precisely, however, the uncanniness is a result of the incarnation of things that still remain visible (without disappearing) even after the decision. The sensation of the sound and movement being repetitive — which are actually reverberating unstably in very subtle dimension and thus include countless perpetuation — is related to this feelings of unrest in the sense that they are never converged into one system. Because the pressure for decision given to the audience is quite strong in Gomyomsom (the audience also has the right to not decide on anything in the exhibition), it does not impose one singular reflection upon the audience. I think that all processes themselves in Gomyomsom are one metaphor, and what it alludes to is not fiction but the very way in which such fiction is created.

This exhibition doesn’t illustrate that the artist’s attitude towards the perception of reality and world has changed. Rather, it looks like a site of experimentation of artistic methodologies that are different from before and the artist’s reflections on how he can intervene in the world as an artist. In looking back on the full account of how Gomyomsom functioned, it arouses contemplations on the dialectic effect of the infinite and the finite. Roughly speaking, it’d be a question on how and what reconstructs the infinite. If the narrative was a way of unifying the infinite, this would, to a degree, mirror Hannah Arendt’s idea of the “holes of oblivion”. On the other hand, even if it accompanies pressure, the fragment of narrative selected in the dormant state of possibility clearly leaves open the possibility for other existence even if it is reduced to a single meaning. The former might seem triumphant because it always seems successful, but the latter always has no other choice but to admit failure. The difference between the two is simple: where has the surplus of the finite gone? This also relates to the question as to how history can be reconfigured, and thus it’s a very important question for us now. When narrative depresses history, what surplus does it generate? Going on further, one might even question how history should be constructed and what fiction it demands. And naturally, history here also includes right here and right now.